Compilations of Great Ideas and Advice from The Instrumentalist Archives

Chamber Music All Year

By Greg Snyder

April 2009

Gregory Snyder is the founder and conductor of the Nashville Youth Wind Ensemble. He is Director of Bands Emeritus for Lakota West High School in Ohio. He taught at Lakota West for 27 of his 35 years as a high school band director.

I have always believed in the solo-and-ensemble process for developing musicianship in students. Years ago, in January and early February, the other directors and I encouraged as many students as possible to enter the Ohio solo and ensemble contest. Every year following the contest, I was pleased with the improvements I heard in each band, realizing that the students’ work, whether they polished a solo or participated in an ensemble, had a direct, positive influence on the overall sound of each band.

Students learned to listen more intently to one another as they adjusted pitch, turned a phrase, and added dynamics to their performances. The increased improvement through chamber playing was all the more inspiring because students did it with a minimum of coaching from the staff. After years of preparing and polishing ensembles for chamber performances in just two months of the school year, I was curious to see whether the level of achievement would increase more if students prepared chamber music throughout the school year.

Last year, I had a remarkable sax group. The members liked playing together so much, they would practice all the time and come in to perform for the band. Their arrangements were always 10-15 minutes long, not the two-minute variety. They would play and play and play. Finally, I would have to say, “Sorry guys, we have to go to lunch.” One of the students is now a college composition major.

Actually, the group went to contest asking for comments only, because Ohio students have to select repertoire from a prescribed list, and the composition student had a newly composed piece that wasn’t on it. They decided that there are more important things than just getting a rating.

That is one of many stories that I associate with the chamber music program. No band is perfect, but I have heard the bands at Lakota West get stronger every year, with a great deal of improvement coming from the chamber program. A chamber program alone does not make for a stellar band program, but combined with private lessons, participation in honor band, support from the administration, and a daily plan to strive for the best performances, great bands are possible.

My Mentors

By RoAnn Romines

October 2009

RoAnn Romines has taught instrumental music for 40 years in Germany, Texas, and now, Maryville, Tennessee.

My mentors were fine directors who knew conducting, music history, and had extensive knowledge of each instrument. I can recall one mentor, Ray Cramer, whose knowledge continues to surprise me. While he ranks high in stature in our profession, he never shies away from sitting beside young band students, helping them review the fundamentals of their instruments with a genuine smile and caring for their success.

Music educators have to become private instructors on all the instruments. It is time to turn back the clock and return to the era when directors had the knowledge of professional players and teachers at their fingertips. Today, many directors seldom play an instrument; many want to be only conductors and usually hire students to teach festival music.

As I did years ago, some directors fear approaching students and giving them precise instructions to develop as trained musicians. This has weakened our ability to teach. Bands seem to have excelled across the globe, and many have changed the perception of arts in the school; but in years to come, without good pedagogy, there will be no one to perform in bands or orchestras.

Listening Objectively

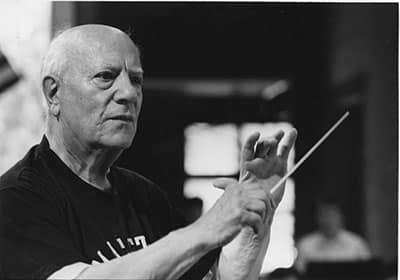

By Ray Cramer

August 1993

Ray Cramer was Director of Bands at Indiana University from 1982-2005 and served as President of the Midwest Clinic for 13 years.

I try to maintain objectivity by recording rehearsals and having others listen to my group. Even when I taught in high school, I recorded every rehearsal because when listening to the tape with the score in front of me, I could objectively hear all the mistakes. The key to being a great rehearsal technician and a musician is hearing everything that goes on.

When teaching in Cleveland, I observed George Szell rehearsing the Cleveland Orchestra. I was fascinated to see that even with the fine musicians of the Cleveland Orchestra, he rehearsed with great detail and had fantastic expectations. He also had incredible ears and could identify minute details in the mass of sound created by this fabulous orchestra. The key for any conductor is hearing as much as possible, but realistically, directors need to sit back and listen to a tape recording to evaluate what actually happened.

The Sound We Imagine

John Lynch

April 2010

John Lynch was Director of Bands and Professor of Music at Director of Bands and Professor of Music at the University of Georgia. He is currently Director of Bands at the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point.

Conducting is an interesting discipline because conductors make no sound. Conducting teachers often talk about looking like the music, but Robert Spano, the conductor of the Atlanta Symphony, says, “More importantly, we want to create the gesture that elicits the sound that we imagine.” That could mean that a gesture doesn’t really look like the music, but it gets the sound that you want. The most important thing is the sound we get, not how we look. Even before I work on technique with students, I make sure they have a strong aural image. Only then does conducting become a matter of using gestures and the body in the most expressive and communicative way possible to get the desired sound.

Student Perspectives

Barbara Lambrecht

June 1991

Barbara Lambrecht has written many articles for us, sharing her wisdom from a half-century of teaching music at every level. She is a cheerful force for good in this profession.

Like all teachers, I have a few students I want to adopt, one or two I want to choke with my bare hands, and many others who come and go without much fanfare. In their own way, each band member is focused, concerned, and creative. I know this because in a recent written exam I asked students to complete this sentence: “If I’ve Learned anything in life, it’s…” The answers were astounding, running the gamut from delightful to desperate, exhibiting everything from boundless faith to crass cynicism. They were often humorous, sometimes sad. Here’s a sample:

“Life is not always fair.”

“You can usually get away with putting things off.”

“You can’t trust a lot of people.”

“You can never win an argument with a certain band director.”

“A trophy isn’t the most important way to prove you’re number one.”

“Mom knows more than I think she does.”

“If you can’t forgive other people for things they’ve done, life is pretty miserable.”

“There is no end to the mysteries out there.”

“Learn from our mistakes. Life goes on.”

“Don’t take life too seriously, and brush after meals.”

Reporters may suggest that teenagers across America lack direction and forecast continued educational decline, but I can report the young people I see daily are turning out just fine.

Project What We Expect

By Amanda Drinkwater

October 2010

Amanda Drinkwater spent 23 years as a highly decorated director in Texas and now is Director of Fine Arts for the Lewisville ISD, which includes 61 campuses.

Students have to feel that there’s a sense of respect, expectation, and trust towards them. They tend to rise to the occasion, so if you project to them a sense of low expectation or lack of trust, they will fill that order easily. When they first get into high school we have to recognize that it’s going to take some time before they become model Marcus High School band members. They’ll get a lot from the upperclassmen simply from watching and learning, and we always speak to them in a calm tone of voice. We try to project the expectation before we demand it. The role of a teacher is to define expectations and only then demand them. The only times we get into trouble with students are when we forget to define first.

Mentors

Alfred Watkins,

December 2017

Alfred Watkins was Director of Bands at Lassiter High School in Marietta, Georgia, for 31 years. Ensembles under his baton have performed five times at the Midwest Clinic.

My mentors included four or five middle school band directors in the Atlanta public school system who were good husbands, fathers, and bandmasters. They taught in deprived communities but with a high level of musicianship, and their ensembles were very good. I learned that poor kids can learn with good instruction. These mentors taught me to be a future husband and father. My college directors, William P. Foster, Director of Bands at FAMU, Julian E. White, Classroom Methods Instructor at FAMU, and my classical trumpet professor, Lenard Bowie, were extremely excellent mentors for me. All were well-trained African-American classical musicians who developed a community of musical excellence for us. The small college program was based as much on character development as it was good musicianship. I owe them everything.

I also sought out Harry Begian, William Revelli, John Paynter, Fred Fennell, and Arnald Gabriel. They were my five mentors outside of Georgia. I called them every month or two and became very good friends with all of them. They heard my groups over the years and offered advice on how to build a program and select literature. All of these directors conducted in my rehearsal room at Lassiter at some point. None of these men ever gave me any formal education, but they were the best in the world at what I was doing, and they shared information with me forever. Harry Begian would come to Lassiter and always stayed at the house with my family. This allowed us to talk shop late at night.

Advice for Music Students

By Harvey Phillips

November 1990

Harvey Phillips was a force of nature in support of the tuba and musical excellence. He was a valued member of The Instrumentalist braintrust for many years.

As you develop your mind and skills, try to become an expert in self-analysis. Learn to know your strengths and weaknesses. Displaying your strengths in public opens the door to many opportunities. Work on your weaknesses in private and endeavor to make each weakness a strength before displaying it in public. Consider the following questions and answers:

Why do you practice? Because you want the option of a career in music as a performer. (Improving your performance is a by-product of practice and not a reason.”

When should you practice? At every opportunity. Don’t limit practice time.

What do you practice? Everything you cannot yet play on your instrument. Plan each session so you know what you wish to accomplish before you begin. Be consistent and tenacious.

Where should you practice? In the most private, isolated place you can find. Practice time is not rehearsal, performance, or audition time.

Don’t limit the exploration of your performance potential. Music is a language with many dialects. The more dialects you can master – baroque, classical, romantic, contemporary, avant garde, jazz, folk – the more you expand your performance potential and enjoyment of music.

Building Trust

By Jason Fettig

April 2019

Jason Fettig served as the 28th Director of “The President’s Own” United States Marine Band and Chamber Orchestra. He is currently Professor of Music and Director of Bands at the University of Michigan.

What are your objectives when you step on the podium with a new or different ensemble?

I think the most important thing when musicians are getting to know each other is establishing trust. It is certainly important musician to musician, and it is equally important conductor to ensemble. Trust is one of the most difficult things to build, but when there is trust in each other, it inspires a freedom of playing that I think is essential to music making.

Trust relates to preparedness. Conductors will trust an ensemble if they feel like that ensemble is prepared and ready to work, and an ensemble will begin to trust conductors they feel are competent, prepared, and committed to what you’re about to do. After that, the trust is an ongoing process rooted in allowing each other to do your jobs. If I am conducting an ensemble and I trust the musicians to play, I am not going to over-conduct or micromanage them. I will instead allow them to be artists, put their stamp on the performance, and collaborate and negotiate without frequent intervention by the conductor. When you empower the players to be part of that process and you trust them to do what they are trained to do, they enjoy what they are doing more, they appreciate the conductor’s work more, and the music is simply better.

Photography

By Milt Hinton

August 1993

Bassist Milt Hinton played on recording sessions for more than 1,000 jazz and pop music singles. He also took remarkable photos of the musicians in his world. We were fortunate to share some of them in our pages.

This is a specialist’s world. You don’t find too many people doubling on saxophone, trombone, bass, and clarinet. You’ve got to do one thing and do it very well or you won’t survive. There is no room to delve seriously into different activities and become professional in any one.

With my photography, somebody gave me a $25 camera for my birthday when I was a young man. Evidently my mother liked photos because I have many pictures my family took as far back as when I was three months old. It was easy to stick a camera in my pocket during my travels. Between sets, on the train, and in the bus, I would take out my camera. For some reason I decided to take pictures of musicians. You will not find very many pictures that I have taken of trees or bridges. My photos are of musicians; they are what I was around and are great to study. Every snowflake is different so there’s no problem making every man different. I wanted to photograph musicians the way I saw them, not the way a photographer sees them. That’s been the preface of the success I have with photos: I am a musician taking pictures of musicians.

The Most Exciting Year

By Robert Foster

September 1993

Robert Foster was Director of Bands at the University of Kansas for 31 years. He is a past president of the National Band Association and the American Bandmasters Association.

Teaching and Phrasing

The most exciting year of teaching in my life will be the next one. There are things I can’t wait to do. I have spent my whole life getting ready for next year. The great fun in teaching is in the learning. The better you learn how to teach, the more fun it becomes….

The best teachers I have known were the senior faculty members who were still enthusiastic about learning. I have a friend in New York who frequently calls to talk about a piece that excites him and that he can’t wait to share with his students. In order to succeed, a director should be competent enough as a musician to make musical judgments while continuing to grow musically.

I’m absolutely convinced that most teachers should spend more time shaping phrases. In performance after performance at contests, ensembles have learned the notes and play most of the dynamics as printed, but they never seem to realize that a piece of music is just a broad set of guidelines, that all notes are not created equal. Some notes inherently have greater value than others and different relationships with other notes to form a phrase. Music communicates through phrases. Merely playing notes does not produce music.

Watching the Audience

By Robert Spevacek

November 1993

When this article first appeared, Robert Spevacek was Director of Bands at the University of Idaho’s Hampton School of Music. He was previousy a high school band director in Delavan, Wisconsin, and is a member of the American Bandmasters Association.

Several years ago, while watching a percussion ensemble perform all of the latest percussion compositions at a state music convention, I happened to turn around and look behind me. What I saw there was a crowd of people with eyes glazed over. They looked like hundreds of deer staring into car headlights. Although the percussionists played splendidly and had worked hard to prepare for the concert, no one in the auditorium wanted to listen to that music.

After this experience, I wondered what the audiences looked like during some of my performances, so I videotaped the next several concerts, but I aimed the camera at the audience from backstage. They were unaware of the taping. I just wanted to find out what held their attention and what turned them into transfixed deer. The results were not entirely startling, but there were enough surprises to make me think about how each piece of music will be received and whether anybody will want to come to the concert to hear it.

In judging the effectiveness of the programming for a concert, directors should not rely on the comments from those in the audience, as these are often misleading. Any audience, and particularly one comprised of parents, will generally praise a performance even if the program consisted of musical genres that were difficult to comprehend. Until fairly recently it was good formula for having no one show up at a concert to program new music. In recent years, however, band and orchestral composers have produced some wonderful new music that educated audiences will come to hear and feel confident that they will be intrigued if not thrilled or entertained. The key to a satisfied audience is to give an excellent performance, one with the right notes played at the right time with good tone and musicality. If those elements are missing, an audience may pay attention to the peripheral details but will not be entranced by the music itself. This is true regardless of what music is on the program.

It is important to remember that audiences like melodies. At the 1984 International Brass Congress at Indiana University, many of the programs were quite traditional with lots of the Carnival of Venice type of music. This was a very sophisticated audience that loved every bit of the tuneful and masterfully played fare. At one time players avoided those old chestnuts and preferred to stay on the leading edge with avant-garde music. If that brass congress had occurred in 1968, the program would have been entirely different.

My programs tend to consist of 50-75% new music that has features that will make people want to listen. My colleague, Daniel Bukvich, has an amazing ability to write pieces that reach across the footlights. His well-constructed compositions frequently incorporate visual elements that excite audiences without being trite. I also include traditional pieces that are proven crowd pleasers.

Reflections at Age 91

William Revelli

December 1993

The legendary director passed away just months after this interview appeared.

Teaching demands a correct attitude and standards that are uncompromising. I had a reputation for being tough, but let’s define tough: an alligator has tough skin. Does being demanding make me tough? I want the music just right. In music, just about right isn’t acceptable. Musicians can’t play a little out of tune or almost in rhythm because that sounds horrible…

Looking back I don’t agree with all of my philosophies during my first year of teaching. One idea, however, that I have never given up is the search for perfection. I didn’t achieve perfection often, but the uncompromising search for it has been the greatest journey of my life.

Great Expectations

I expect every student to give the best he has not to me, but to the composer, the composition, and to the art of music. Music has to be serious, and a player has to do the very best he can…. You should rehearse to learn the piece well enough to put your whole self into recreating a score written 100 years ago. You have to forget everything else. Your mind has to be focused right there. I don’t want to rehearse a person whose mind is thinking about something else. The Italian word for rehearsal is probo – prove – and that means to prove you are ready. A rehearsal is not somewhere to sightread music. That would be a sightreading session.

Coaching

One of the finest men I’ve ever met is Bo Schembechler, who coached at the University of Michigan. Inside, he’s a marshmallow who cries as quickly as I do. Outside everything has to be right. When he started at Michigan, I was the first faculty member he met. I went to his office to talk about the football activities that were upcoming. He came to one of my rehearsals and stayed for 45 minutes when I thought he would be there for only five minutes. The next day he asked me to talk to the team. I replied that I knew nothing about football, but he countered, “I don’t want you to talk about football. I want you to say exactly the same things to my team that you said to that band yesterday.” I still talk to the team every year. I did it this fall for the new coach. I relay my philosophy to the team. If you don’t love football, don’t play it. Do something else.