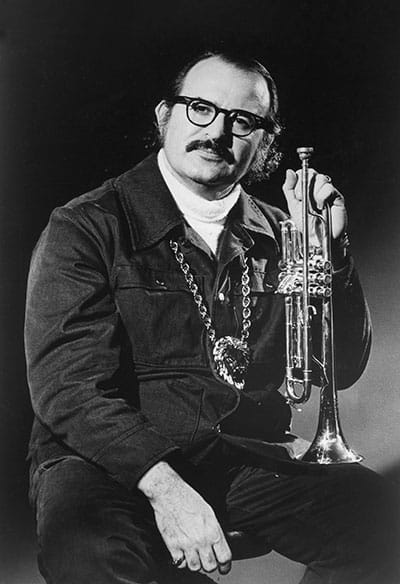

An Interview with Ron Modell

The legendary Ron Modell passed away on June 10, 2025, at age 90. He was a good friend of the magazine and penned a regular column for us over many years. We reprint this interview from August 1994 in full as a tribute to one of the essential figures in the development of jazz education over the last several decades.

At age 18 Ron Modell was principal trumpet of the Tulsa Philharmonic Orchestra and became principal trumpet of the Dallas Symphony in 1960. He has also played lead trumpet for Tony Bennett, Billy Eckstine, Vic Damone, and Della Reese. Modell taught at Kansas State Teachers College, Southern Methodist University, and the University of Tulsa, his alma mater, before joining Northern Illinois University in 1969. He founded the NIU Jazz Ensemble, which has won the respect of artists, educators, and audiences for its musical achievements. While celebrating the 25th anniversary of his leadership of the jazz ensemble, Modell reflected on the past and shared his thoughts about future plans.

How have you consistently maintained outstanding ensembles over the years?

The consistency of the program stems from the philosophy that we are servants to the music. Egos have no place within a group, and band members should treat each other like family. When the lead player of a section can’t handle a particular type of playing, it is his duty to switch parts with someone. These attitudes and achievements, once in place, motivate the new members of the band to feel they must reach the same level of the previous year’s group.

My goal was to make the first jazz ensemble as good musically as possible. The enthusiasm of the students was incredible. When I announced auditions, 60 students showed up. I picked 20 students, and we began rehearsing on Wednesday nights from 10 p.m. to midnight. This was the only time slot the music department would allow.

As the program developed, I guess my enthusiasm for the music rubbed off on the students because without any prompting from me, they asked the chairman of the music department to schedule more than one two-hour rehearsal per week. The second semester the band met from 5:00 p.m. to 5:45 p.m., three days per week. By the second year the band was given a legitimate rehearsal slot, 10:00-10:50 a.m., four days a week.

In those years, I would call the band together for three days at the end of the school year – not to rehearse, but to talk. The first day I would talk to the band about what we had and hadn’t accomplished, what I thought should’ve been done and didn’t get done. Then the following two days I allowed them to suggest whatever they thought would improve the program.

Was your classical training a help or a hindrance in teaching jazz?

After studying classically for over 20 years, I suddenly discovered the Count Basie Orchestra through recordings and was converted to big band music in the mid-1950s. Mel Tormé had great musicians with him, particularly the Marty Paich Dek-Tette, which had my all-time favorite trumpet player, Don Fagerquist, plus Pete Candoli, Herb Geller on alto, and Red Mitchell on bass. This was a great group.

After listening to Basie and Tormé for hundreds of hours, I found that my symphonic training under some five conductors merged with my new interest in big bands. I was amazed that even in the first three years of teaching, all of the classical training I had as a child came through. I already had learned how much dedication and devotion it took to reach a high level of playing. When I came to Northern Illinois University, there had never been a note of jazz played on campus. Once a year the members of Phi Mu Alpha pulled out what we used to call stocks, such as an old Johnny Warrington dance arrangement of I’ll Remember April.

Not long ago I took out the tapes of our earliest ensembles and was surprised at how they sounded. The repertoire was very simple such as Cute by Basie and the theme from The Pink Panther. The most difficult chart that we did the first year was a piece Woody Herman recorded in 1963 called Watermelon Man. I’m not sure if Quincy Jones did the chart, but it was half what I remember of Watermelon, and then it went into a swing thing – it was fairly challenging.

What changes did you make in the early years of the jazz ensemble?

Earlier in my career I fell into a common trap for directors, featuring only one or two outstanding soloists. In the late 1970s or early 1980s, a student disagreed with my approach to improvisation. He said that while the best soloists should appear during public performances, every student ought to have the chance to learn improvisation with the band. This comment was an eye-opener for me because he was absolutely right. Our jazz ensemble is not a professional band but part of an educational institution. The next semester I made sure that every student played a solo. When handing out music, I still instruct students to give any solos to the players who feel most comfortable with that style of music.

Now, if students ask for a chance to work on a particular style, I give them an opportunity to rehearse the solos. The support players give to each other is one of the most beautiful things that has happened in my bands. On our tours, students will frequently pass up solos on certain nights to give others a turn in the spotlight. Whenever a student has a relative in the audience, I try to feature them on the concert. Many people are astounded by how much fun students have on stage. I am never surprised, because the musicians are doing what they love best. For 25 years I have told the players before every concert to go out there and have some fun.

How do you decide which music to program?

When we traveled to the Elmhurst Jazz Festival in the early 1970s, the festival director, Jim Cunningham, said that the Northern Illinois band was the only one he took time to hear. He explained that the band was the only one that picked music to please the audience rather than to win the contest. I have always believed in performing all types of music well, not in competing with other bands.

In some years, half the band was absolutely nuts about Duke Ellington and Count Basie, and the other preferred the multi-rhythm work of Don Ellis. My job was to bring together both groups by persuading the Ellington-Basie people to enjoy playing in the 3316 time of Don Ellis, while convincing the Don Ellis faction to understand that musicians who can’t play older charts well will never make contemporary music sound good. There’s a groove to all jazz. Players have to develop the groove with Basie and Ellington before graduating to Stan Kenton. For 25 years I have encouraged every student to approach each chart with integrity, to master it regardless of personal preferences.

Did you plan from the beginning to use guest artists in your program or did that gradually develop over time?

In the beginning I invited our faculty members to play with the ensemble, but we started bringing in soloists after an appearance at the Elmhurst Jazz Festival in the early 1970s. One of the biggest names in jazz judged the festival, and the students were thrilled to meet him. Later, I saw that his evaluation sheet was blank except for his signature. I learned that while the band performed on stage, this star was in the hall talking with a friend.

On the bus that night, the disappointed band asked how much it cost to travel to Elmhurst. On learning that our expenses were $1,200 the students urged me to spend that money to invite a guest artist next year who would work only with our band.

In 1973, I invited Mike Vax, the lead trumpet and road manager with the great Stan Kenton Orchestra, to join our band for a week-long tour of small towns between DeKalb and St. Louis. This tour gave students a chance to experience life on the road, staying at a different hotel every night. Over the years, our tours have helped students decide between a career in music education or performance. We would travel on a bus, set up the band, give an afternoon clinic/concert, and then an evening concert. We now take a four-day tour in November and an April tour, but these are scheduled so students rarely miss more than three days of school in a year. The teachers don’t mind the missed classes because the jazz program has been a great recruiting tool for the university.

As soon as I arrived at Northern Illinois, I called Chuck Suber, publisher of Down Beat, and asked where I could recruit good high school jazz players. He suggested District 214 in the northwestern suburbs of Chicago because several high schools had great jazz programs. I called each school and offered to play an assembly in exchange for our bus costs. These early high school tours were a big success, partly because we had a young singer who captured the essence of the popular 1970s rock groups, Chicago and Blood, Sweat &Tears.

How do the artists react to performing with your band?

Over the years Louie Bellson has done more tours with our band than anybody else. While we performed in Harlan, Iowa, in 1978, Louie said, Your band plays my charts better than my band.” I was flabbergasted because his group included some of the greatest players in Hollywood. He said that once pros get to know the book, each performance just becomes another night of music to them. “With your students, it’s brand new very night. Their enthusiasm makes me play better than ever.” Through the years, I have heard similar comments from Clark Terry, Dizzy Gillespie, and Slide Hampton.

Most guest artists have been completely taken aback by experiences on the road with us. While traveling for a week on the bus, the artist and students have an opportunity to talk about music and life. The guest artists share experiences and wisdom that students cannot ever get in a classroom. These guys have been out and done so many things they are encyclopedias of knowledge about jazz and what life is all about. Thank goodness, in practically all cases, they are more than willing to share these thoughts.

Where do you find the money to pay for guest soloists and tours each year?

Our program of soloists has continued to expand even with only a tiny budget of one or two hundred dollars a year. The only way to raise money for guest artists was to spend hours calling high schools and colleges trying to book concerts. The point never was to make money. All I wanted was enough funds for the bus and solo artist, putting the band up in a decent hotel with no one sleeping in the same bed. I’d arrange for seven triples: two double-beds and a roll-away in each room, plus separate rooms for any ladies in the band, another for the sound engineer, one for the artist, and one for me. With those eleven rooms, I could usually obtain a discounted room rate. In many cases, we just made it through without going into the red. A couple of times in the beginning years, I took my checkbook out in order to balance the books. Recently, the university has given us more financial support. It was becoming difficult to stay on the phone for two or three hours a day trying to find places to perform. While the administration didn’t give us additional money each year, we now have permission to go into the red temporarily.

For your 25th anniversary tour, you brought in your mentor, Leon Breeden, as guest soloist.

Anyone who knows Leon thinks of him as the dean of jazz education. Between the years 1959 and 1981, he brought the college jazz band to prominence. His North Texas State group was the first college group to play at the White House. In those days, when you heard college jazz, you immediately thought of the North Texas State One O’Clock Lab Band. From the outset at Northern Illinois, I followed Breeden’s goals. He said that when a band could play every concert with over half of the compositions being written or arranged by students, it had reached the pinnacle. Our first recording includes some marvelous student compositions and arrangements, and student writing has dominated every recording after that. Leon also urged me to be honest to all arrangers and composers by reporting all recordings to ASCAP and BMI, so the composers receive royalties. We never copy music unless the parts are unavailable, and the composer gives permission.

For 25 years students have had to audition each year for a place in the band. Just because a student played last year does not guarantee a spot this year. In most cases we have long nights of auditions. This approach keeps the door open for young players who want to make the group. Occasionally I’ve let people go because another student played a much better audition.

How has jazz education evolved over the past 25 years?

The writing has gone through several transformations, and the difficulty of the music today is astounding. I would be completely out of it if I tried to play some of these charts. When we started in 1969, Sammy Nestico had written his first Basie album, including That Warm Feeling and Basie Straight Ahead. For a long time all the colleges and high schools played Nestico charts because his writing was great. Then, for a period of time, the Thad Jones/Mel Lewis band became popular and schools across the country played Central Park North, Us, and Groove Merchant. Through the years, Bob Mintzer’s charts have been widely played. The new kid on the block is this wonderful writer from New York, Maria Schneider. I can tell from the pulse of my band how much they enjoy playing her music, and we’re trying to introduce her work to a broader audience.

The level of performances by high school ensembles has improved dramatically. We have worked with Janis Stockhouse at Bloomington North High School in Indiana for several years, and I get goosebumps over how she handles students and teaches improvisation. She’s not the only one. This year I judged Jim Culbertson’s band from Decatur McArthur High School and Don Shupe’s band from Libertyville, Illinois. These people and others consistently turn out some of the best high school jazz groups in the country. I’ve always said when high school programs play on such a high level my job becomes easier. By the time these students reach college, I don’t have to spoon-feed them on playing particular phrases. My work then becomes polishing their skills.

On the negative side there are still many directors who pick music their bands cannot play. With abundant repertoire there is no excuse for this. At some festivals I want to ask certain directors, “What’s wrong with you? Give your band challenges, but let the students reap the rewards of a great performance by selecting music they can handle.” It is also frustrating when bands play a chart in the wrong style. Many band directors have no knowledge of correct jazz styles and never take the time to study recordings or play them for students. When some bands perform at contests, the adjudicators almost want to laugh because the style is so completely wrong for the chart.

Though you’re most visible as a jazz ensemble director, you continue to teach classical trumpet, and that field has evolved, too.

I played principal trumpet in the Dallas and Tulsa Symphonies for 15 years before coming to Northern Illinois. The number of people auditioning for a symphony orchestra job is perhaps 100 times higher than in my day, and now there might be 300 applicants for a third trumpet job in North Carolina. When a student expresses a sincere desire to learn orchestral repertoire, I am eager to help. However, every trumpeter studies with the other trumpet professor at Northern for half the time, and half with me. I certainly don’t know it all, and giving a student another slant on playing is one of the greatest things you can do.

I usually do not teach freshmen or sophomores because my expertise is in polishing the music. I am less well-equipped to resolve the major playing problems that some young players have. Over the years I have sent several students with radical playing problems to work with Vince Cichowicz and Burt Tobias. Cichowicz is the recognized trumpet doctor in this part of the country. He can figure out the problem immediately and send the student on the path to success.

I am still excited by talented students who are serious about their studies and come prepared for each lesson. For 25 years, I have played at every lesson with every student because it is important to set an example for students. When studying with Arnold Jacobs, I once asked what he does for a player with poor tone quality. Jacobs responded, “Make sure you play at least 50% of the time during each lesson with that student so your skills rub off by osmosis.” As he would say, the old stimuli are pushed down, and new stimuli are brought in.

In addition to teaching private lessons, I like to get out and solo at least three to six times a year. Not a year has passed that I didn’t play a solo with either our wind ensemble or philharmonic. Performing shows people what’s happening with my playing.

As for trumpet method books, not much has changed. My colleagues and I still use the Clarke technical studies. My favorite is an out-of-print method by a composer named Gatti. This book has some of the most musical studies and duets ever. I also use the Clodomir method book. Although a tremendous amount of material exists, I find that most teachers go back to the basics. The Schlossberg book is the bible of trumpet, and my uncle Louis Davidson’s book Trumpet Techniques has excellent studies.

I never really got into 20th-century techniques. Even 25 years ago I decided that some of the 20th-century trumpet compositions and techniques were just not for me. The great Russian trumpeter Dokschitzer was asked about what solos he studied when he was young. Translated from Russian to English, here’s exactly what he said: “I try to practice every solo that I can get my hands on, but I only play those in public that like me.” I think that was a great remark, that we should stay in our own ballpark and do what we do well but to have the opportunity to play through everything. If I’ve been lax in anything, it is in the area of 20th-century playing techniques, but I am getting better.

What are some of your fondest memories?

The 1978 tour with Dizzy Gillespie included a concert at the National Association of Jazz Educators convention, which was hosted by one of my dearest friends, the late Don Jacoby. That Saturday night concert brought us to national prominence. People came up afterward and asked, “Where in the world is DeKalb, Illinois?”

My dear friend and mentor Leon Breeden had never heard the band in person, and it was a great thrill to hear his compliments. He said, “Not only did the band play great, but your programming was absolutely sensational.” I was pleased by his comments because I take so much time planning the pacing of our concerts and albums.

In 1981, PBS produced a one-hour special by having a professional producer follow the band around for the year. I always hated the title: A Year in the Life of The Greatest College Jazz Band in America and argued that there are 10 or 15 great jazz bands, but the producer said it wouldn’t work to sell us as the second best.

It was a personal highlight when you and I took the band to Switzerland for a program sponsored by Motorola for 115 executives. We explored creativity and motivation in music and in business, and I was able to share with them how the love of music and the students is so important to this ensemble. This has been foremost in my rehearsals and performances.

The most challenging repertoire during my career was the charts of Bill Dobbins when he toured with the band in 1991. I didn’t want to scare the students but I told them it was the hardest music I’d ever seen. Dobbins went home exhilarated after his week here. Coming from Eastman, Dobbins was treated to a new experience on the tour bus with an outpouring of love from the students. They picked his brain just as they did with Louie Bellson, Dizzy Gillespie, and James Moody. So there are the thrills. I would have to sit down and write a book to capture the memories of all the great artists. Every time an artist such as Clark Terry walks on that stage it is a thrill of a lifetime for me.

The worst moments of my career occurred when three evil students made it into the jazz ensemble. Their negativity spread throughout the band, and it was the only year-and-a-half of my career that was miserable. I didn’t even want to go to rehearsals. I approached these three as a father and a teacher and tried to show them that their attitude was wrong.

The more I did, the worse the situation became. I finally called these students into my office and told them to change their ways or leave the band. You can’t save everybody. I have followed these students’ careers and found that they are causing similar problems years later. They were talented and could have become fine musicians and human beings. To avoid the heartache and miserable rehearsals, I would have been better off going with lesser musicians and avoiding that kind of poison going through the band.

One year four saxophonists wanted to skip the January tour because of problems with the fifth member of the section. I convinced them to make the trip because we had signed contracts and made commitments. I also asked each of them to invite the problem student out for a cup of coffee or a coke during the tour and to have a little compassion. Perhaps they could find out why the student acted so abrasively. Each night of that tour a different saxophonist spent time with this student. This person changed completely and won the student-voted award the following year for making the greatest contribution to the success of the band.

With many rumors over the years about your retirement, what are your plans for the coming years?

Despite these occasional problems, I decided 15 years ago that if anyone ever offered me another job, I would not leave Northern. I love the faculty and the staff. I will stop teaching full-time in May 1995 but have agreed to lead the N.I.U. Jazz Ensemble for two additional years. In May 1997, I will retire completely. After some 40 years of teaching, I will have paid my dues and hope that some high school and college directors will invite me to work with their jazz ensembles or to solo with their concert or jazz bands. Perhaps some directors will want to pick my brain about what makes a jazz program a success.

Our success with the jazz ensemble is not only a tribute to me but to the faculty, administration, and mostly the kids who put in the time and effort to bring it to the highest level. It has been a wonderful 25 years; and except for that year-and-a-half, I wouldn’t change a thing.