For people who play an instrument, even more than for most, amputation has always been the tragic companion of war, in modern as well as historical conflicts. Disease has also caused musicians to suffer various handicaps impairing their ability.

For people who play an instrument, even more than for most, amputation has always been the tragic companion of war, in modern as well as historical conflicts. Disease has also caused musicians to suffer various handicaps impairing their ability.

In March 2008, Pan (the magazine of the British Flute Society) ran an article by Jan Lancaster about Rebsomen, the one-armed flutist. In 1813 while Napoleon was fighting his last campaigns as the scourge of Europe, Anne Toussaint Florent Rebsomen, an adjutant-major of the Imperial Guard, later known as the Chevalier Rebsomen, was critically wounded. On the battle field, his right leg and left arm were amputated by the legendary French surgeon Larrey. He received every possible medal for his valor and eighteen wounds over seventeen years of service, but what he wanted most was to be able to play the flute again. And he did. He invented a flute, called “solimane” (one-handed) with eleven keys at a time when pre-Boehm flutes had between four and eight keys.

Little is known about the music he played, but history credits him with a pleasing talent. The article speaks also of present day people impaired by accident or illness, who, thanks to clever designs and passionate hard work, are able to overcome their handicap and play their beloved instrument.

My purpose however is different. Even for the able-bodied flute player, it is useful to know that close to half of all notes of the flute range can be played with one hand – the left. This tells us a lot about how our instrument works and provides insight into how to approach technical practice. Last but not least, it gives us an opportunity to solve difficulties that affect finger combinations, especially in the higher range of the flute.

The difficulty of the flute, and of all woodwinds, is what I call Finger Antagonism, which means fingers working in opposite directions. Practice helps of course, but try as I may after many years of playing, the Bb/G connection (with the “real” fingering of the right index) is never smooth enough for my taste. I have the same problem with the C5/D5 connection. This most common of configurations is a bridge that we cross many times daily, and it can be uneven (C: 2 fingers down, the rest up; D: 5 fingers down, the rest up, back and forth, the more repetitive the harder). I stabilize this connection by using, you guessed it, the Bridge Fingering. I will come back to that in a later article.

The attention should be for seamless continuity in finger phrasing before facility, but having both is even better. Facility is even more precious in the third octave where finger antagonisms prevail practically on every note and interval. Once again, practice is essential but it helps to know what finger combinations create most problems.

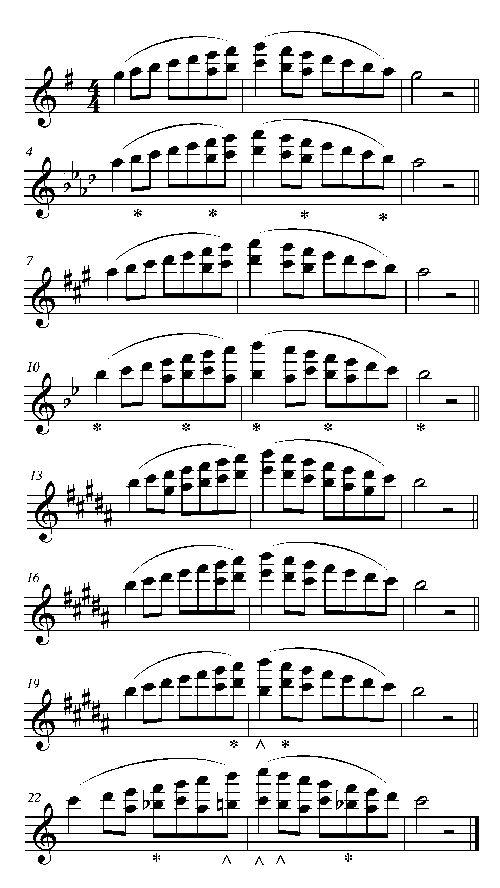

Practically all the notes in the third octave stem from harmonics of notes whose fundamental is a 13th below. For convenience’s sake we will assume that they can be fingered a 5th below. Starting with G5, which is the exact center of the flute range, play the following example, fingering the lower note when there are two indicated:

Scales in Harmonics

* – This B flat/A# must be fingered with thumb B flat

^ – B natural and C are fingered with left-hand ring finger down

The right hand, for the sake of this example, is not involved in fingerings. However, stability, a constant issue in the high range, is insured by holding the right hand over the brand name at the junction of the center joint and the headjoint or at the bottom part of the foot.

The consequence of this sequence is that regardless of however perfectly the right-hand fingers are coordinated, it is vital to coordinate the left-hand fingers for the third octave. The high notes are affected more by the left hand, especially those keys closing or venting the holes closest to the embouchure plate, most of all the C key, which is our octave key.

In a recent article about the Prokofiev Sonata (September 2008), I hope I showed that emphasis on the left hand considerably helps the virtuosity of licks and patterns in the third octave.

Finding solutions and easier fingerings requires thought and analysis. It is not a cop out or a cheat, as long as the purpose and result are a better musical quality in difficult passages and a greater smoothness in finger phrasing.

Home > The One-Armed Flutist

The One-Armed Flutist

SHARE THIS ARTICLE

In March 2008, Pan (the magazine of the British Flute Society) ran an article by Jan Lancaster about Rebsomen, the one-armed flutist. In 1813 while Napoleon was fighting his last campaigns as the scourge of Europe, Anne Toussaint Florent Rebsomen, an adjutant-major of the Imperial Guard, later known as the Chevalier Rebsomen, was critically wounded. On the battle field, his right leg and left arm were amputated by the legendary French surgeon Larrey. He received every possible medal for his valor and eighteen wounds over seventeen years of service, but what he wanted most was to be able to play the flute again. And he did. He invented a flute, called “solimane” (one-handed) with eleven keys at a time when pre-Boehm flutes had between four and eight keys.

Little is known about the music he played, but history credits him with a pleasing talent. The article speaks also of present day people impaired by accident or illness, who, thanks to clever designs and passionate hard work, are able to overcome their handicap and play their beloved instrument.

My purpose however is different. Even for the able-bodied flute player, it is useful to know that close to half of all notes of the flute range can be played with one hand – the left. This tells us a lot about how our instrument works and provides insight into how to approach technical practice. Last but not least, it gives us an opportunity to solve difficulties that affect finger combinations, especially in the higher range of the flute.

The difficulty of the flute, and of all woodwinds, is what I call Finger Antagonism, which means fingers working in opposite directions. Practice helps of course, but try as I may after many years of playing, the Bb/G connection (with the “real” fingering of the right index) is never smooth enough for my taste. I have the same problem with the C5/D5 connection. This most common of configurations is a bridge that we cross many times daily, and it can be uneven (C: 2 fingers down, the rest up; D: 5 fingers down, the rest up, back and forth, the more repetitive the harder). I stabilize this connection by using, you guessed it, the Bridge Fingering. I will come back to that in a later article.

The attention should be for seamless continuity in finger phrasing before facility, but having both is even better. Facility is even more precious in the third octave where finger antagonisms prevail practically on every note and interval. Once again, practice is essential but it helps to know what finger combinations create most problems.

Practically all the notes in the third octave stem from harmonics of notes whose fundamental is a 13th below. For convenience’s sake we will assume that they can be fingered a 5th below. Starting with G5, which is the exact center of the flute range, play the following example, fingering the lower note when there are two indicated:

Scales in Harmonics

* – This B flat/A# must be fingered with thumb B flat

^ – B natural and C are fingered with left-hand ring finger down

The right hand, for the sake of this example, is not involved in fingerings. However, stability, a constant issue in the high range, is insured by holding the right hand over the brand name at the junction of the center joint and the headjoint or at the bottom part of the foot.

The consequence of this sequence is that regardless of however perfectly the right-hand fingers are coordinated, it is vital to coordinate the left-hand fingers for the third octave. The high notes are affected more by the left hand, especially those keys closing or venting the holes closest to the embouchure plate, most of all the C key, which is our octave key.

In a recent article about the Prokofiev Sonata (September 2008), I hope I showed that emphasis on the left hand considerably helps the virtuosity of licks and patterns in the third octave.

Finding solutions and easier fingerings requires thought and analysis. It is not a cop out or a cheat, as long as the purpose and result are a better musical quality in difficult passages and a greater smoothness in finger phrasing.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Michel Debost

Michel Debost is the former principal flutist of the Orchestre de Paris and flute professor at the Paris Conservatory and Oberlin Conservatory. He is the author of The Simple Flute.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

2026 Directory of Summer Camps

Davion

ADVERTISEMENT

Order your Marching and Color Guard Awards this Fall!

Orders may be placed through the online store, by email (awards@theinstrumentalist.com) or by calling 888-446-6888.