Sometime during the school year, you may be invited to present a flute masterclass in the public schools. This can lead to many benefits for your flute studio, especially if you are just starting out. It also provides much needed information for band students who may not study privately. If you have not been invited to teach a class, call the band director or music supervisor and offer your services. Consider teaching a series of masterclasses during the year to cover the basic curriculum.

Class Length

Most band classes are from 50 to 70 minutes long. Find out how much time you have to organize and pace the class correctly. The curriculum should include information about the flute, musicianship, practice techniques, and something fun in conclusion.

Start with the Headjoint

If this is your first time teaching in the public schools, you may be shocked to see where the performance level is and what the students actually know about flute playing. Your natural inclination may be to teach what interests you rather than teaching what the students should learn. Using the headjoint alone avoids the need to talk about balancing the flute, positioning the hands, standing and sitting positions, and fingering. It is better to start simply with the headjoint and make sure that students understand how it works, where to blow, how to tongue, and the basics of vibrato before assembling the flute. These will be topics for future masterclasses.

Curriculum

This curriculum works well for any age level. The goal for the first class is to teach students how to produce beautiful sounds, articulate, and vibrate. This is most easily done using only the headjoint, which they should hold with their thumbs and index fingers. The left-hand fingers should not block the air stream as it crosses the embouchure hole.

Preparation

You will need a one-page handout for each student, soda straws, small plastic storage bags, a pinwheel, a cleaning rod with a cork placement marker on one end, a tuner, and a Bigio insertion tool. The Bigio tool is available from J.L. Smith in Charlotte, North Carolina or you can make one by drilling a small hole in the end of a ½" x 12" dowel rod.

Getting Started

Each student’s headjoint cork should be checked for proper placement. To save time, do this before the class begins when possible. (The information at the end of this article offers guidance, although some of the suggestions are for more thorough cleaning and adjustment at home.) The line on the cleaning rod should register in the center of the embouchure hole. If you are uncomfortable adjusting corks, take a lesson from a flute technician to learn how to do it safely or follow the directions in the box on the following page.

If a cork is too loose in the headjoint and does not stay in place, remove the cork and place a strip of pipe or cellophane tape around the base of the cork. This quick fix will last until the student can take the headjoint to a technician for a permanent repair. The class will be playing on the headjoint for almost an hour, so you want them to be in tune.

Sweet Spot and the Soda Straw

Teacher’s Goal: Find the Sweet Spot on the headjoint.

Every headjoint has what I call a sweet spot – the optimum place at which to direct the air to produce a ringing, bell-type tone. A soda straw helps students find the correct location. With the straw in the right hand, as if it were a pencil, and the headjoint in the left hand not touching the chin, have students place the bottom edge of the straw on the back edge of the embouchure hole – the edge that would normally be under the lower lip. Then have them blow while slowly moving the straw across the back side from left to right. Listen carefully. There will be one place where the tone will be more focused. This place is position A, which might be in the center of the back edge or a little off to the left or right. This position depends on the individual cut of the embouchure hole.

Then, with the straw in position A, angle the straw while blowing the air toward the outer edge – the edge furthest away from you – and move the straw from left to right. When you hear the best focus, that position is position B. As you blow from position A to B you will find the sweet spot. Now try to duplicate that blowing position with the headjoint against the chin. This exercise really helps students understand how to find the best place to direct the air for a great sound and focus.

Anatomy and Blowing

Teacher’s Goal: Align the head, separate the vocal folds, place the embouchure hole parallel to the ceiling, release the air from the body.

Position the head at the bottom of a very small nod. To understand how the head balances on the spine, ask students to nod their heads several times and also have them pant several times in order to notice that the vocal folds are separated during inhalation and exhalation. This position, sometimes referred to as an open throat, is what they should feel while playing.

Check that embouchure holes are parallel to the floor and ceiling, not facing back toward the player. The inside edge of the embouchure hole should be where the skin changes from chin to lip.

While students blow several notes, feel with your hand where each student’s airstream is crossing the embouchure hole. Place the pinwheel at that spot and instruct the flutist to make the pinwheel spin. This teaches them that the air must leave the body when playing the flute. It also helps students increase the speed of the air.

Embouchure Development

Teacher’s Goal: Make a smooth octave slur.

Practicing slurred octaves on a headjoint is a quick way to develop the embouchure. Ask students to slur half notes several times, low to high, at mf. Alternate with the students – you play one slur and then the class responds. When the class is small, you can work with students individually. If someone has difficulty making the slur, ask the entire class to play the low note while seated and then rise to a standing position for the upper note. The energy that is used to stand is what was missing in the previous attempts to produce the upper note. By asking the entire class to do this exercise, you don’t embarrass the student.

Joseph Mariano taught students to increase the air speed just before the upper note to make the interval sound easy. William Kincaid taught to slightly lengthen the note before a slur if the interval was a fourth or more.

Generally, when playing slurs from a musical perspective, we play large intervals small and small intervals large. Octaves on the headjoint are not in tune, even when the cork is in the proper place because the headjoint is not completely cylindrical. How-ever, the parabolic shape makes third-octave notes less sharp when using the entire flute.

Encourage each student to play with his natural face. I prefer to let embouchure’s evolve rather than giving explicit instructions about mouth shapes to young students. Exercises with harmonics will help students’ embouchures evolve naturally.

Every criticism sheet that I received during the years I was playing school solo festival competitions mentioned that I did not play with a smiley face. The corners of my embouchure were down naturally, and my aperture was on the left side. The judges suggested that I change my embouchure immediately.

Thank goodness I was a stubborn young student. I thought I sounded pretty good. I was winning contests, and did not see why I should change. Then I played for the legendary Frederick Wilkins at the Tri-State Music Festival in Enid, Oklahoma, who commented, “You have a beautiful embouchure. The corners are down and your aperture is on the left. Did you know that all the famous flutists had an aperture on the left?” I was glad I had not followed the advice of a less-informed band director whose only flute playing experience was in a methods class.

Over the years I have changed only about 10 students’ embouchures. When I have made an embouchure suggestion, I have prefaced it with the words, “This is only a suggestion.” Those I have encouraged to change were students with apertures on the right. While they were able to get beautiful sounds that way, I was concerned with how far back their right shoulders had to be in order to play. I worried that they would not be able to play this way without pain for four or more hours a day for 40 years. However, before any changes were made, we studied the arm’s anatomy and talked about what modifications might be made. The goal is to teach the student so that he may continue performing all through a long career.

Tonguing

Teacher’s Goal: A perfect attack.

The tongue releases the air to produce a sound. The general movement of the tongue should be horizontal rather than vertical. Say the word thicka several times quickly to achieve the snake-like tongue motion. The jaw should hang with the upper and lower teeth separated, and the tongue should be placed through the teeth.

When the air comes before the tongue, a hoot attack is produced. Remind students over and over again that the tongue releases the air. When an attack is harsh, the beginning of the note is sharp, and then the note settles into the pitch. A tuner will show the beginning of a note.

Ask students to hold the ends of the headjoint with thumbs and index fingers and start the tone (using the sweet spot) with the tongue outside the lips, as if making a face. Pull the tongue back horizontally to release the air and make a tone. Repeat several times until they understand the motion and can easily start the tone with the tongue out. Now repeat the stroke placing the tongue on the top lip and drawing the tongue back while saying thi in the rhythm: thi, thi, thi, rest.

Musicianship

Goal: Strength of the beat concept.

Each masterclass should teach basic musicianship fundamentals. In the past, many teachers delayed teaching musicianship until students’ early-teen years, but I have had excellent results teaching basic musicianship techniques to beginners. The strength-of-the-beat concept works well while teaching tonguing, and the chart below will be useful.

Simple time

(beat divisible by 2)

2/4 strong, weak

3/4 strong, weak, weaker

4/4 strong, weak, less strong, weaker

Compound time

(beat divisible by 3)

6/8 strong, weak

9/8 strong, weak, weaker

12/8 strong, weak, less strong, weaker

Research shows that muscles learn faster and with less stress when practice occurs in small chunks with a rest between each event. In 2/4 play three eighth notes in the lower octave followed by a rest (thi, thi, thi, rest). The stress is strong, weak, weaker on each unit. Repeat until the quality of the stroke is excellent and simple. Now tongue four 16ths on the first beat and one eighth note and rest on the second beat. The first note is strong with all the following notes weaker.

After several repetitions ask the flutists to remove the headjoint from their lips. This will give them practice finding the sweet spot from a cold start.

With each repeat, remind students to position the head at the bottom of a small nod, face the embouchure hole to the ceiling, look and listen for the sweet spot, have the vocal folds separated, and finally blow.

Skills

Teacher’s Goal: Explore the tongue and vocal folds.

There are five skills to practice: thi, cka, hah, tk or tkt, and vibrato. Practice each of these strokes, omitting vibrato, on the headjoint in rhythm. (thi, thi, thi, rest; cka, cka, cka, rest; hah, hah, hah, rest, t k t rest, tkt t rest) The cka should be forward and as high in the mouth as possible.

Vibrato

Goal: Basic vibrato cycle.

Vibrato is produced by air moving through slightly opening and closing vocal folds. To open the vocal folds, say hah, which places the vocal folds at their widest separation. When you say hah, hah, hah out loud, the vocal folds will close slightly in between the hahs. Georges Barrere named this hah, hah, hah stroke throat staccato early in the 20th century.

To teach students where the vocal folds are and how to engage them to produce vibrato, ask them to say hah, hah, hah, silence, in 2/4 as eighth notes. Add a slur to the hah, hah, hahs, and they will produce vibrato. This exercise is best at a piano dynamic level.

Visual Aid

With a small plastic bag on the end of the headjoint secured with a rubber band, ask students to blow into the embouchure hole to fill the bag with air. Next practice the hah, hah, hah, silence exercise, both staccato and slurred. When done correctly, the bag will bob up and down in time. When students get a good even bob, they are on their way to a good vibrato. Try a variety of rhythms, with and without vibrato.

End With a Fun Activity

The clever arrangement of The Snake Charmer by Phyllis Louke in Flute 101: Mastering the Basics, Volume 1 by Phyllis Avidan Louke and Patricia George is a fun way to conclude a masterclass. Students make the lower sound by covering the end of the headjoint with their right palms. The upper note is produced by opening the end of the headjoint.

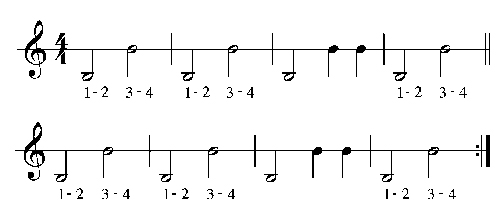

Student part:

Teacher part:

A one-page handout will help students follow and remember the lesson. If they like your masterclass, there is a good chance they will call in the future for flute lessons, so include contact information. List each topic covered in the class and leave space for note taking. Writing notes in their own words will help students recall the information at a later time.

Sample Handout:

Flute Fun – Masterclass #1

Headjoint Only!

Presented by Your Name

Flute Studio

Your address

Your phone number

Your email

Headjoint

Check the cork

Sweet Spot and the Soda Straw

Where and angle

Anatomy and Blowing

Nod head, Pant, Pinwheel

Embouchure Development

Clown lips/lipstick lips,

Low/high slurred

Tonguing

Thicka

Musicianship

Strength of the beat concept

Skills

thi, cka, hah, t k t rest, tkt t rest

Vibrato

Hah, hah, ha, rest: staccato and slurred.

Plastic twist and tie bag.

Flute Fun

The Snake Charmer

Your Biography

Keep it brief and simple

Aligning a Headjoint Cork

1. Unscrew the crown several turns.

2. Place the end of the crown on a padded surface and gently push the crown in. Keep your hands away from the embouchure plate while doing this.

3. Once the cork/stem assembly is free, remove the crown and push the cork out the far end of the headjoint with a cork/stem remover tool. This tool has a hole drilled in one end so you can place the hole over the screw part of the stem .

4. When the cork has been removed, wash the headjoint inside and out with dishwashing liquid and hot water. Hot water removes the wax and other debris from the inside of the headjoint. Dry the headjoint thoroughly.

5. To replace the cork assembly, drop it into the headjoint, screw end first, from the flute-body end of the headjoint.

6. A well-fitted cork should drop into the headjoint and come to rest so that the disc on the end of the cork rests in about the middle of the embouchure hole. The cork should also be shaped so that it is smaller toward the screw end.

7. Use the cleaning rod to position the cork. The line on the cleaning rod should register at the half-way mark in the embouchure hole.

7. Use the cleaning rod to position the cork. The line on the cleaning rod should register at the half-way mark in the embouchure hole.

8. Replace the crown and use the crown for the final adjustment.