Etudes were always a part of my practice routine growing up. After plowing through the first Rubank books, which were full of tidbits of studies, I remember opening up an entire book of just etudes and thinking, “Wow, a whole page long – I must be getting really good.” I frankly don’t recall which collection it was, most likely one of the easier Andersens, such as Op. 37 or 41. (Danish flutist Joachim Andersen wrote 48 sets of flute studies, as well as concert pieces for flute.)

From there followed harder Andersen etudes (Op. 21, 30, and 33 and the more advanced Op. 15 and 63); daily exercises such as Barrere’s Flutist’s Formulae, Andre Macquarre’s Daily Exercises, Reichert’s 7 Daily Exercises, Taffanel-Gaubert’s 17 Daily Exercises, and the two “big yellow books,” The Modern Flutist and Bach Studies. There were other collections, but these were the ones that stood out for me.

The Modern Flutist introduced me to composer Donjon’s elegant Salon Etudes and the late-Romantic German composer Karg-Elert, who wrote the highly chromatic and expressionistic 30 Caprices. The Modern Flutist also included many little bits of flute music from orchestral works that I had a vague idea were somehow important. I later learned that these excerpts represented big solos in major orchestral repertoire and were the ticket to glamorous principal flute positions all over the country.

In the meantime, I just learned to play the notes and had the etudes checked off one by one. My primary motive for earning that check mark was to get to the duets I loved at the end of each lesson. Though my teachers considered me musically sophisticated for my age, at 14 and 15 I was still too young to appreciate the styles of Karg-Elert and Donjon and even less prepared to understand the musical context for the excerpts. It was dawning on me that I didn’t really know why I was practicing these pieces that were not pieces.

The Bach Studies came to my attention late in high school, by which time I had more awareness of Classical music. I recognized many of the tunes and knew that some of them were originally keyboard pieces by Bach, but that was about it. No one told me, for instance, that the Courante, #11, was part of a glorious solo cello suite, or that the Presto, #24 was from a monumental solo violin partita. I loved playing what I could in that collection but also felt irrationally uneasy about it. I wondered why I was studying works that were not written for flute, and why they were called studies anyway. Weren’t they real pieces of music? These and other questions that arose as I played etudes through college and then taught them became the catalysts for an approach to etudes that has taken several decades to put together.

My early somewhat jumbled etude experience was due in part because I worked with a number of different teachers during high school, and each had his or her own method and preferences about studies and daily exercises. Although I learned much from them, these teachers never really explained where the etude collections came from and how they would specifically help my flute playing. Also, I worked through some of the collections too early in my technical and musical development, which caused considerable frustration while simultaneously arousing my curiosity and the desire to overcome my limitations.

Flute Students Today

Today, developing flutists in middle and high school are more knowledgeable about flute literature, and they have the chance to hear marvelous playing and teaching at flute festivals and summer workshops. However, even with such awareness, opportunity, and rising performance standards, I realized that I was not the only one confused about the subject of etudes. This became evident when I was asked to participate as a master teacher in a pedagogy session called “Etudes: What’s the Point?” at the 2007 National Flute Association Convention in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Teachers don’t question the necessity and value of scales and related daily exercises. The solo repertoire often follows standard developmental paths that result from competition lists at local and national levels. Although teachers may differ on which solos they teach and when they introduce them, our top ten lists are probably similar. Etudes are the one practice area for which there are questions about their value and purpose.

Purposeful Etudes

One of the best ways I have found to make our multitude of etudes meaningful is to link them to the repertoire, whether it is solo, chamber, or orchestral. As soon as a teacher relates a specific etude to solving a technical problem in a solo piece, the etude has a perceived purpose and importance. Finding the right etudes to tackle the problem at hand is the challenge, and it takes enough experience with both repertoire and etudes to know where to look. The point of etudes, in this sense, is to turn them into active aids for learning repertoire.

Instead of dutifully heading through all 12, 18, or 24 etudes in a collection without any critical response, we should use our intelligence and ears to pick out the best ones for the purpose at hand. No composer of etudes provides 100% inspiration and the solutions to all the technical or musical concerns he sets out to solve, and no flute student at any level is receptive to every etude in a book.

I believe we can save time and learn more effectively by being attentive to the etudes that address our particular weaknesses. Carrying this concept a step further, I would like to examine a major piece in our repertoire using etudes and daily exercises that highlight its uniqueness from a technical point of view.

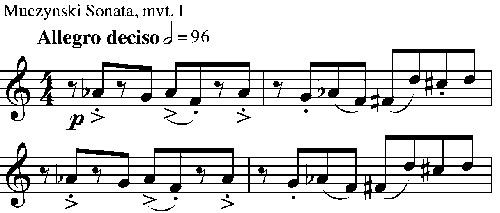

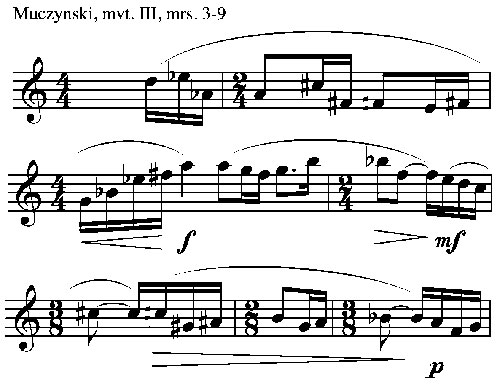

Robert Muczynski’s Sonata for Flute and Piano, Op. 14 is a masterpiece of terse energy and compact, efficient structure from beginning to end. Without wasting a single note, he manages to convey a surprisingly large emotional spectrum within an often driving rhythmic setting and a harmonic/melodic centering on chromatic, minor pentatonic, and blues scales. With much of the flute line in the low to middle registers, one of the first considerations for a successful performance is focus and projection of sound in this range. The question is how to achieve the forceful energy that Muczynski demands and do it with incisive articulation and a compact sound.

Focus and Sound

In the low and low-middle registers, the embouchure and throat positions are crucial in order to center the sound successfully. Taffanel-Gaubert’s Daily Exercise #7 is excellent for embouchure positioning and strengthening.

Because it targets the range between middle B and A, it is necessary to even out the inherent disparities between the open B-C-C# and the denser D-E flat-E. Three key factors are required to tackle the problem: a proper airstream angle, a strong upper lip, and a fast air speed. The angle, determined by the upper lip position, must be down enough to focus the C#, the flakiest note in this range. Be sure to move the upper lip forward before lowering the angle of the air stream to ensure greater embouchure flexibility and freedom of sound. Bearing down with the upper lip muscles that surround (but do not include) the center and sending fast air through the flute will allow you to penetrate the stuffy E flat and E natural. Those pitches should be the focus for this part of the exercise.

Here is the sequence:

1. Take a good breath and hold it, feeling the abs firm and the pressure of air in your lungs.

2. Set the lips in a fairly wide opening and send the upper lip out over the blowhole and then down, feeling the side muscles around the center bear down. You are setting the position for the C#.

3. Release the air at a fast rate, being sure to keep the abs firm the whole time; do NOT let them relax as you release the air. The air speed should be gauged to handle the stuffy E flat, no matter what pitch you are playing. An immediate improvement in all the other notes will be evident as well.

Practice the exercise slurred and very slowly at first. When you have gained lip strength and a consistent tone quality, you may add the tongue as long as it doesn’t interfere with the lips or airstream. The next step is to play the opening of the Sonata’s first movement in this way: all slurred, very slowly, and with great concentration of air and embouchure.

Play other sections of the movement in this range the same way. Then try it with articulation, being careful to maintain strong and even sound. The combination of embouchure strength (to cut through the low middle register) and an overall focus into the low register works well for much of the Sonata.

Singing the Notes

The other exercise I suggest for finding the best embouchure position for the opening of the first movement, as well as the fourth, is to sing and play the pitches. If you have never attempted this before, I refer you to Robert Dick’s Tone Development Through Extended Techniques, page 9 and onward. He explains carefully how to set your throat so that it resonates in the optimal position for the note you are playing. Throat tuning, as he calls it, is one of the most effective ways to find the best resonating position for a particular note in the mouth and throat.

Play the note first, and then sing it with your flute in playing position. Next sing and push your lips forward into a long funnel with a small opening, blowing air up over your singing (this is what it feels like to me) and through the lips. You will have a buzzy, airy sound that should approximate the pitch you are singing. With practice, this becomes natural and opens the sound greatly. Try just one pitch at a time at first; singing even one note in tune with your playing will make a significant difference in the openness of all the notes in the range.

Articulation

Now that you have a centered sound and good definition with a strong embouchure, it is time to address articulation. This is extremely important for clarity in all registers but especially the low and middle. Moyse’s 24 Little Melodic Studies, # 18, is a staccato exercise in the first octave of a C# minor scale.

As in many parts of Muczynski’s Sonata, Moyse requires a firm embouchure that does not move during a series of short notes in a forte dynamic occurring in the low register. First play each staccato note slowly and without the tongue, using only the impetus of your abs to send an “air shot” for each note. Try to maintain a firm lip position, which is more difficult with extra air coming out but very instructive in making you aware of how much articulation has to do with airstream. When you can get through a couple of lines, go back and repeat with the tongue, trying to keep everything else the same. At this point, you are still exaggerating the movement of the abs and the amount of air produced, but using your tongue should make the sound a little clearer and release the air more cleanly. Keep the tongue stroke light at the tip and let the air support do the hard work.

The lesson to learn is that the most incisive articulation comes from strong abdominal pressure, strong lips to funnel the fast air coming through the lips, and a consistently light tongue. If this is a new concept, you will be surprised at how the sound leaps forward with energy and clarity and how the initial ictus of the tongue sounds much cleaner than one with a heavy stroke and lots of tongue. Armed with this new technique, you can play the Sonata’s opening accented section (see previous example) by using the abs to produce the effect and the tongue simply to release the air on its way out.

The next stage of Moyse’s exercise is to control the abdominal movement and avoid lurching on every note while playing with the same firmness and articulating from the abs. This allows you to move faster. The ability to play fast and light in the low register will provide better focus and less air in the sound. You will feel lots of pressure propelling sound and articulation forward with more air behind the sound. There are two Moyse variations to add at this point – one with 16ths in fours and the variation of sextuplets. In the sextuplets, I suggest the double-triple articulation, if possible, for fastest and lightest effect: t k t k t k.

Two etudes helpful in increasing endurance and strength for this kind of articulation are found in Andersen Op. 15 and Soussmann’s 24 Grand Studies. Andersen’s Op. 15, #18 in F minor begins with precisely the same range and note patterns as the opening of the Sonata.

Practice the eighth-note measures with both single and triple tongue; the latter is useful for the Sonata’s Scherzo movement. The etude’s middle section is a melody with very fast, fleeting articulation underneath. Although this tonguing is not directly relevant to the Sonata, the feat of playing the entire etude with light, fast, and clear articulation will pay off in stamina as you work through the Sonata.

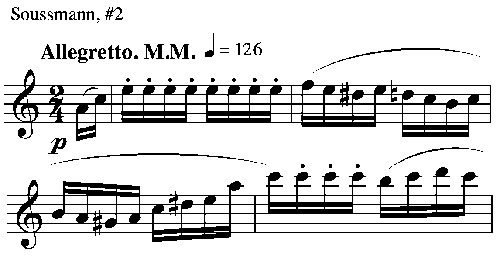

Soussmann’s excellent Grand Studies, available separately as Part III of his Complete Method, are a truly advanced set of etudes that represent one of the best lesser-known collections.

Etude #2 in A minor deals with the muddy range around middle E and uses a repeated-note staccato motive throughout. His instructions imply a forward tongue placement, “without touching the palate.”

This is the other critical articulation element for clarity in the Sonata. The tongue should be forward with just the tip touching the back of the teeth, so there is a minimum of movement and maximum of response. A single-tongue exercise as dictated by Soussmann, you can also practice #2 with double tongue and strive for the same evenness as with single.

Melodic Lines in the Sonata

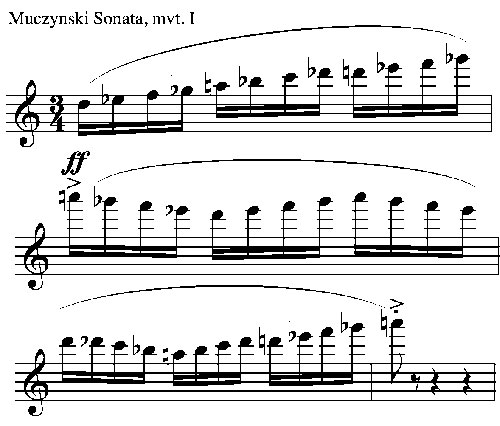

Muczynski’s melodic lines, both short motives and long phrases, are predominantly constructed of major and minor seconds and thirds and chromatic patterns. Some passages have a harmonic minor cast to them due to the combination of minor seconds and minor thirds, which can be found in the first movement five measures after #13,

the fourth movement in measures 4 and 5 of the cadenza, and from #47 (the 5/8 bar) to the end.

.jpg)

Muczynski’s use of the jazz blues scale is evident at the start of the second movement in measures 1-9. The first six notes spell out the blues pattern 1, 3, 4, diminished 5, and 5 (with a diminished 4 – the E flat – thrown in as passing tone).

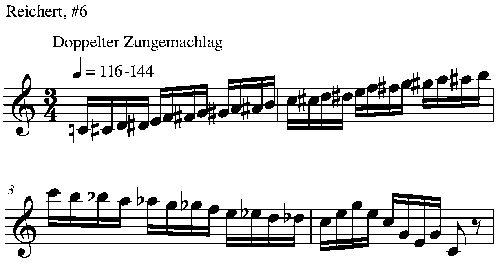

The demands for facility and speed in all but the third movement sent me searching for exercises with minor and chromatic writing as well as complex interval structures. The most cut and dried of these is #6 in Reichert’s 7 Daily Exercises, which is a very fast, double tongued, chromatic series in all keys.

The key sense comes from the arpeggio at the end of each scale. The exercise is very taxing when you tongue it all. In the beginning start by alternating with slurred scales. The finger-tongue coordination required in #2 in Reichert’s will be very helpful for numerous passages in the Sonata’s fourth movement, including the opening bars and much of the cadenza to the end of the piece, where intense sound is also needed. I suggest using a large and forceful airstream in these scales, whether tongued or slurred, and going for as much power as you can and still maintain a focused sound. I describe this sensation of massive air as a whoosh of motion through the flute.

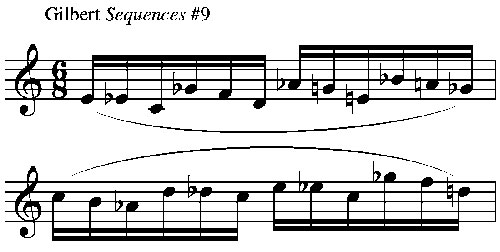

For the fingering patterns that are not quite chromatic and not quite minor scales, there are two exercises in Geoffrey Gilbert’s Sequences. This is a book of patterns based on scales and chords that Gilbert was working on while I was a student at his master classes in the 1980s. (He tried out ideas with the class to see if we approved.)

Etude #6 in Gilbert’s book is a series of leading tones (half steps) and major chords. The perfect fit for the Sonata would have been minor chords, but this is still very close to many patterns in all the movements – a minor second followed by a skip of a third followed by more minor seconds. This exercise is easy until you push the tempo and try to do all the articulations that Gilbert suggests. The goal is to play the pattern until it is almost second nature.

Exercise #9 includes sequences on chromatic scales and is a dizzying series of downward and upward seconds and thirds.

Again the patterns require time to assimilate and play rapidly. Passages in the Sonata that benefit from these two studies include the ones already cited from the first and fourth movements. Almost all 16th-note passages in the three fast movements offer some form of altered chromatic or minor pattern. The few regular scale passages include the E-major runs on the first page of the second movement, the B-major scale towards the end of the third movement, and the B flat-major run in the opening of the fourth movement, which becomes a D-major run in the cadenza.

For that special painful moment in the Scherzo at #24, when the right pinky can develop serious cramps in four short measures from the repeated low C-D flats, there is an extremely effective pinky exercise in Trevor Wye’s Practice Book vol. 2, Technique. Twelve patterns sliding from low C or C# in various excruciating combinations will strengthen the pinky finger with short sessions daily.

The pinky’s position makes a significant difference in comfort and ease of movement. Angle the entire right hand slightly down towards the foot joint, so that the pinky can curve and rest on the key toward the outside edge. This position offers more maneuverability and takes off much weight and pressure which allows faster sliding.

The Sonata’s moments of legato, sustained lines are few. The third movement offers relative calm, but even the opening sinuous melody has more unrest than resolution. I think that the fewer breaths in the first 11 measures the better, in order to preserve the tension of the long phrase.

If possible, try to make it to the middle of measure 3 in one breath. Breathe again in the middle of measure 5. At this point the phrase keeps being extended, so try to make it to the downbeat of measure 9 for your last breath.

To play the opening expressively with additional breaths is acceptable; to play it with the breaths I suggest takes the music to a more rarified place. To extend your breath capacity, try practicing the solo from Afternoon of a Faun. The super breath that I take in two parts before Debussy’s solo – one big inhalation to the lungs, another while holding the first one to the upper chest – serves me well in these first three bars of the Muczynski. The same goes for the absolute evenness with which we must parcel out the air in Faun. Interestingly, the range of notes is almost exactly the same in the Muczynski as is the smooth-as-glass texture of the line. You will extend your breath capacity almost immediately for the Sonata by gearing up for it the way you would for the Faun solo.

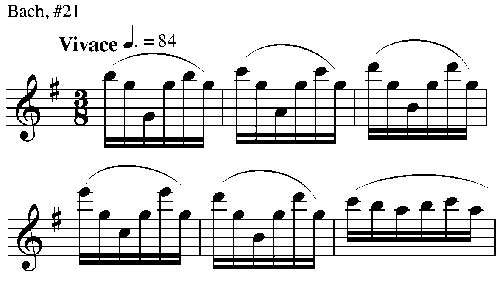

The other legato writing occurs mostly in the final movement at 38 and 41. Here the smoothness of the line is at odds with the tension, and our job is to make that point by playing extreme legato with little expression, as though trying to smooth over the underlying emotion. These phrases have large dropping intervals, always more difficult to execute than upward ones. We must keep the air going, drop the jaw, and change the air angle at just the right moment. To practice this, #21 from the Bach Studies is perfect. Originally a keyboard piece, this G-major Prelude uses a broken-chord figure that is natural for hands on the piano but unidiomatic for flute.

Here lies an answer to one of my early questions about playing transcriptions: they stretch our limits precisely because they were not written for us. Master the smooth downward jumps of a sixth, seventh, or an octave in this study and you will have no trouble with the jumps in Muczynski.

Learning Muczynski’s Sonata with the help of these etudes will give you more insight into the true nature of the piece’s technical makeup than you would have from simply practicing the piece on its own. This approach does take more daily practice time; you may wonder, “Can I afford to spend the hours to learn three etudes, four daily exercises, etc., when my degree recital is coming up in three months?” Time is always of the essence in recital preparation, and managing time is one of the lessons you should develop. I have found that the time spent working out technical problems in the repertoire through exercises and etudes that specifically target those problems actually saves time in the long run. Instead of sweating it out over the passage in my recital piece – which has much at stake – I can redirect that pressure to an innocuous etude and focus on the purely technical issues without injecting my recital angst into the mix.

I learn faster when I detach playing problems from emotions. When I go back to the recital piece, I have new confidence that often surprises me. The research into my etude collection has made me a more effective teacher. I may still place the entire Andersen Op. 15 on a student’s stand, but we no longer set forth on the page-by-page trek to the end. We may cover all 24 etudes by the time we are done, but the journey will have lots of detours, side roads, and U-turns along the way. The triptych will be designed for that student’s stage and playing qualities and for the solo music she is learning. It turns a seemingly dry and irrelevant practice experience into a vital part of the success of a concert performance.