Teaching rhythm to an instrumental group is always a struggle. One of my teachers, Roger Rocco, once told me that the most common question he was asked as a teacher was “How does this go?” This question poses a dilemma for teachers. Ideally, we want to teach students to make sense of rhythms on their own. Some students are spectacular sightreaders from the beginning while others struggle with it through college. One growing field of music education research offers possible answers for the best way to approach teaching rhythmic notation: neuroscience.

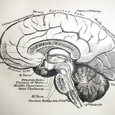

There is a science to rhythm, and our brains process rhythmic information in a precise way. Rhythm is inherent to our cultures and our everyday lives. Our bodies have natural internal rhythms controlled by a part of the cerebellum, which is in the very back of the brain. It is a lobe that contains the thickest neural tissue in the entire brain. Every animal with a backbone has a cerebellum. Reptiles and amphibians only have a cerebellum, which is why many neuroscientists refer to the cerebellum as the reptilian brain. This portion of the brain regulates the internal rhythms of the body including heartbeat, balance, and breathing. It is also the part of the brain that primarily reacts to rhythm in music. It likes a nice, steady beat (similar to your internal rhythms) and can make you move to tempo.

When teaching rhythm to students, you should employ this internal sense of steady rhythm. Most elementary students are already aware of a steady beat. They can repeat a short rhythmic sequence in an echo exercise and can sing a short song with a steady rhythm rather easily. They can do this without even being aware of it because their cerebella have developed basic motor skills such as standing, walking, and singing since birth.

Teaching methods for learning printed rhythms should rely on this innate working knowledge of rhythm. At first I tell students to ignore the numbers under the music (the rhythmic analysis) in their method books. Teaching analysis to beginners is like teaching etymology in a first grade reading class. The information might help later but does not assist students in reading and performing basic exercises. Instead, I model exercises after a first-grade reading lesson. Because students speak before they can read, they should also be able to play rhythmically before reading music. Their ears should be engaged in the music lesson instead of focusing on the printed music. This cements the sound in their heads so they can reproduce it later. The cerebellum must be engaged before any further learning can take place. When the cerebellum is comfortable feeling the rhythm, then introduce what the sound looks like.

At this point introduce small, basic reading variations to help the students apply what they have just learned aurally. For example, demonstrate the following rhythm and have students echo it.

When they can play it comfortably, you can then go over the analysis. Start with the basics of analysis, such as time signature and beat identification. Show where beats one, two, three, and four are. Use the time signature to explain why we only count to four, and use the quarter and eighth notes to show the differences in note duration. Explain the differences in the look of the notes, specifically the ones that are barred together. Avoid going much more in depth; students need not think too hard about the analysis yet. The next step is to change it slightly.

The small variation teaches that two black dots that are joined together go by faster, but evenly, than ones that are not. Continue to make the variations longer and more complex with more eighth notes, half notes, rests, and duets on different rhythms. The trick is varying the rhythm slightly instead of repeating the same exercises over and over. Once players can identify and perform the written rhythm, they are ready to learn the analysis, which is a frontal lobe process. I think of teaching from the back of the brain forward.

Just as students do not become literate by reading the same book repeatedly, musical literacy comes from playing a variety of music. Simply memorizing repeated rhythmic patterns does not help when faced with new rhythms. The better focus is developing a rhythmic vocabulary that can be applied in a variety of ways.

With older students these techniques transfer well to more advanced subdivisions. These subdivisions often prove difficult for middle school students.

It is important that students can identify the ways that these two patterns sound different. If the cerebellum and auditory cortex (located in the mid-brain) cannot decipher the difference between these two patterns, reading and performing them correctly will be impossible. Once again, think about teaching the brain from the back to front.

When the brain can decipher the notes by sound, it can then process the written notation and anticipate changes. This anticipation occurs in the frontal lobes. This frontal part of the brain allows humans to anticipate future events. We learn to anticipate based on experiences. As our brain reacts to external sounds, it develops an entirely different set of expectations.

Recently, I was playing tuba in a rehearsal of El Salon Mexico by Aaron Copland. The low brass parts are mostly on the strong beats, however the meter alternates between 5/8 and 6/8 with a 7/8 thrown in for fun. Students struggled with the changes. Our brains are always anticipating what will happen next, but some music does not lend itself to this. It takes a change of approach to perform the offset beats.

The way to teach it is by fooling the brain and turning off its ability to anticipate. Because anticipation occurs in the cerebellum, it is necessary to preoccupy other lobes with information so we do not try to anticipate the offset beats. We do this by subdividing. The eight note is constant (and can be anticipated), but the accents and hyper-rhythms are not. We occupy the cerebellum with the eight note pulse while the frontal lobes process the offset beats. Put more simply, we subdivide.

Subdivision is a feeling in the cerebellum. It is a more accurate way to anticipate what comes next. By the time students learn to subdivide, they already know the concert of pulse. The key to progress on subdivision is exposure and analysis. I love music that uses compound meter and asymmetric time signatures and listen to it regularly. I can anticipate compound meters such as 78 and alternating 34 and 68 much better than my students simply based on exposure to music. The music students listen to often uses common time signatures, and few seek out anything that is different.

Progressive rock and heavy metal have many examples of these time signature. Because most students are more familiar with rock and pop music, they will be more open to the music and be able to remember the sounds better.

I recommend the following songs for introducing asymmetrical meter:

Schism by Tool (12/8 as 2+3+2+2+3. Tool rarely sticks with one time signature for long).

Clocks by Coldplay (8/8 as 3+3+2).

Living in the Past by Jethro Tull (10/8 as 3+3+2+2).

Hanging Tree by Queens of the Stone Age (10/8 as 3+3+2+2). The subdivisions in these songs move slowly enough to allow students to process the asymmetry and find the groove. Unless they have heard this type of music before, they will not properly hear the subdivisions, and if students cannot hear it properly, they will not be able to play it or analyze it.

Teaching by rote before learning the notes is not a new concept. However, neuroscience research expands on this idea by giving further insight on what happens in our brains as we process information. That continuing knowledge can help teachers improve their methods.

Suggested books:

This is Your Brain on Music by Daniel Levitan.

Musicophilia by Oliver Sacks.

Music, the Brain, and Ecstasy by Robert Jourdain.