This gem from our archives originally appeared in the August 1976 issue of The Instrumentalist.

Early in my career as a conductor I remember feeling somehow cheated if the group before me was poorly balanced or lacking in the needed instrumentation. I continually looked for bigger forces to command, for that Utopia where all chairs would be filled with competent players, eager to be led to the heights of artistic satisfaction.

Sound familiar? Enough of my intimate colleagues have voiced the same thoughts to make me realize that many young conductors probably share this common longing. Perhaps our attitudes are to be expected. As students we were encouraged to reach for the stars, and after all, young musicians tend to see only the glamour of the professional music world beckoning to them like a siren on the rocks. We studied our scores, hearing the smooth, well-balanced sound of a Chicago Symphony, not the struggling, asthmatic efforts of a school orchestra. And then reality struck! We took a position with a 30-piece school or community orchestra, and those dreams were lost in frustration and disillusionment.

There are several typical reactions to this situation. Some directors plow through the pages of a score, conducting as though they were indeed facing a great orchestra. They simply ignore what it really sounds like, indulging their private Walter Mitty fantasies – and they often put on a heck of a show on the podium! Others prefer to take it out on the players through barbed criticism and sarcasm. Such conductors let it be known that they resent working with a less-than-perfect ensemble. They see themselves as unfortunate victims of a cruel fate who have a right to be nasty because their orchestras don’t deserve them (well, at least they’re right about the last part).

Then there is the martyr’s approach. Throughout the rehearsal these conductors lament, “If only we had more violins, oboes, horns, basses, etc., it would sound good.” This attitude passes along the conductor’s personal sense of disappointment to everyone in the orchestra and eventually generates despondency and a sense of hopelessness among the players. The group feels defeated – and they play like losers.

However, now and then one encounters a conductor who sees a so-called hopeless situation as a challenge and approaches the problem with enthusiasm. For these imaginative men and women, music doesn’t make them, they make music. Sure, it’s more exhilarating to lead a fine professional orchestra. The musical rewards are built in. But there are also rewards in taking a feeble, unbalanced ensemble and creating something musically worthwhile with it, and in good conscience, we do want the members of our orchestras to have satisfying experiences. It is not their fault that instruments are missing. So we must do the best we can with what we have, no matter how scrappy and illogical our instrumentation may be. Even poor instrumentation can be made to sound good.

Seating

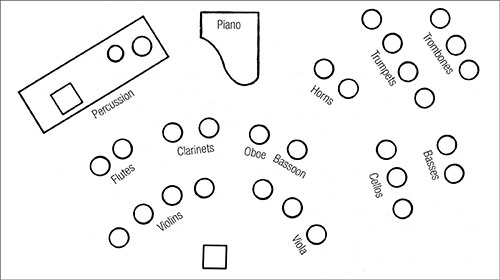

As conformists (and competitors) we want our groups to at least look like the big time, so we seat them in the conventional 19th-century orchestra tradition, but this standard formation often puts an unbalanced group at an even greater disadvantage. Second violins are strung out so that they sit somewhere in the vicinity of the horns or percussion, the brass face forward so that their sounds strike the audience (and the backs of the heads of most of the orchestra’s mid-section) with full force. Our semicircles look great in the annual photograph, but the actual sound can be garbled and few players can hear themselves, or anyone else, very well. What a difference when we seat a small string section in a semicircle around the podium, each member facing forward! Woodwinds also benefit from curved seating patterns rather than the usual platoon-style rows, and brass will not be so overpowering if placed at the sides of the orchestra, facing inward. These seating arrangements will greatly aid the players in relating to one another and in hearing themselves. Also, smaller sections won’t feel so intimidated.

For example, let’s say you have six violins, one viola, three cellos, two basses, two flutes, one oboe, two clarinets, one bassoon, two horns, four trumpets, three trombones, piano, and full percussion. To make the group sound good try an arrangement like the one shown at the top of the next page. Depending upon the relative strengths and weaknesses of your players, there are several possible arrangements to try.

Doublings & Substitutions

You can double weak parts effectively with other instruments, without losing the intrinsic character of the orchestration. Here are some possibilities.

Flutes

Trumpet with cup mute

Eb clarinet, played pianissimo

Oboes

Trumpet with straight or shastock mute

Solo violin or viola, perhaps con sordino

Eb clarinet

Soprano saxophone

Guitar

Clarinets

Soprano saxophone

Violas

Trumpet with shastock or cup mute

Bassoons

Trombone with solo-tone mute

Cellos

Tenor saxophone

Three clarinets in unison, in low register

Euphonium or upper-register tuba, played piano

Bass clarinet

Horns in lower register, played slightly staccato and pianissimo

Horns

Trumpets played into stands or with hat mute

Trombones with hat mute

Cellos, especially if they divide, arco and pizzicato, to resemble tonguing attack

Clarinets behind a baffle or into a box

Bass clarinet

English horn

Saxophones playing pianissimo, without vibrato

Trumpets

Oboe, preferably two in unison

Clarinet and oboe doubled

Soprano saxophone

Viola in upper register

English horn in upper register, played staccato

Trombones

Cellos

Bass clarinet

Euphonium

Bassoon, preferably doubled

String basses, dividing arco and pizzicato

Horn in lower register, played slightly open

Tuba

String bass

Two bassoons in unison

Contrabassoon or contrabass clarinet

Baritone or bass saxophone

Piano playing octaves at bottom of keyboard

Violins

Any woodwind instrument, phrased and articulated to correspond with the printed violin bowings

Trumpet, legato with straight or harmon mute

Violas

Two or three clarinets, in middle or low register

Trombone in shastock mute

Horn stopped or muted

Alto saxophone played pianissimo

Cellos

Euphonium

Trombone with cup or hat mute

Bassoon, preferably two in unison, playing piano and legato

Bass clarinet, preferably two

Basses

Tuba, possibly with mute

Bassoon, preferably two or three in unison or doubled with bass clarinet

Contrabassoon or contrabass clarinet played staccato

Bass trombone with cup or hat mute

Piano playing octaves in lowest register

Harp

Autoharp

Piano with pedal down, played piano

Marimba

Clarinets, pianissimo, doubled with pizzicato in strings

Guitar

Bass clarinet, marcato, doubled with pizzicato in cellos

Piccolo, played piano and staccato in lower or middle register, doubled with bells, played with very soft mallets

The important thing to remember when doubling and substituting instruments is that the effect results as much from the dynamic level and style of playing as from the instruments used.

Choosing Music

Much of our traditional orchestra music gives the hard stuff to the higher instruments, while other members of the group accompany with simple chords or after-beats. The poor first violins work themselves into a lather while the lower strings and winds huff and puff on dull, uninteresting harmonic figures. Pieces that have long, simple melodic lines on top and put more active harmonies and rhythmic patterns underneath are harder to find but they enable student orchestras to sound better. Ron Nelson’s Jubilee and Ippolitov-Ivanov’s Procession of the Sardar are two good examples of such pieces. The brass parts supply wonderful rhythmic underpinning, the woodwinds function as fillers, doublers, or soloists, while the strings perform easy, soaring melodies and sound great.

Rewriting String Parts

Because most of the music we play originated before wind instruments became such versatile orchestra members, we find ourselves severely taxing the strings much of the time, while allowing the winds to develop dry rot. Traditionally, demands on string players are heavy, and few student string sections have the technical ability to fully meet the challenge. It takes a bit of work, but the smart director can alleviate this problem. Passages can be rewritten so that the strings play in unison or octave sustained notes while the winds take care of the harmony and counterpoint. Let the winds do more of the tough virtuoso work while the strings sustain the harmonic base, if your players’ techniques call for it. The charts of today’s pop songs and film scores demonstrate how effective easy string parts can be. It is better to have less flourish and more solidarity than a ragged, failure-prone string section trying to play beyond their capabilities. Give the poor kids a chance to sound good once in a while!

Even very young string players sound good playing pizzicato. Rearrange some passages so that solo wind instruments or sections play legato while the strings play pizzicato and you’ll clean up many messy problems. Bowed repeated notes played in a rhythm that mixes eighth and sixteenth notes are easy, and sound a lot more virtuosic than they really are.

Better Use of Brass

Brass players can play softly, but we seldom take full advantage of this stunning effect in our school orchestras. Look for places to add sustained pianissimo brass chords, especially in low registers where the sound is rich and won’t cover up the thinner strings. Crisp brass articulation (good staccato) will allow the string quality to come through, while sluggish attacks obliterate everything and cause the orchestral texture to be heavy and dull. For more subtle color changes, trumpets and trombones can play into their stands.

The “Wire Band”

Nothing hurts the orchestra director quite so much as the comment “Sounds like a band,” but anemic strings are all but lost when challenged by a full wind section accustomed to the loud dynamics they play in the school band. Since band arrangers have done so well by pilfering orchestral literature, why shouldn’t orchestra directors go to good band literature for their repertoire? Band pieces are less linear, are generally less difficult, and usually transcribe nicely. Besides, much of it is good music. The winds would then have enough to play and the strings could play enhancing parts full of unison and pizzicato passages, in lower, safer, richer ranges. The resulting sound is full, flattering, and quite orchestral.

Percussion Color

How sad it is that we neglect those eager supernumeraries of the orchestra. We wouldn’t feel that percussionists are extras if we understood and used the many colors they can bring to the orchestra. Adding bell tones, mallet passages (played piano or pianissimo), and batterie accents; reinforcing melodic accents with the incredible variety of instruments and beaters available; or even using the wonderful sounds you can make from junk all contribute to the color spectrum of your ensemble. If you have a scarcity of the usual color instruments (oboe, English horn, bass clarinet, viola, harp, etc.), make up for them through the use of color percussion. It can be just as effective.

Piano and Organ

The piano is usually looked upon as an orchestral cop-out, a last resort to fill out the harmony or replace missing parts. Well, it is a cop-out if the pianist continually plays a drab mezzo-forte, semi-legato, without giving a thought to the varied color possibilities on the instrument. Imaginative use of pedals, different articulations, and exploration of double and triple octaves are but three very obvious nuances available. When doubling a line in the orchestra, the pianist should strive for interesting sounds to complement, rather than intrude upon, the orchestral texture. Plucking the strings with the fingers for certain notes can highlight a passage the way a harp can, and depressing the sostenuto pedal can serve as an acoustical reinforcer for the entire orchestral sound.

The electronic organ is widely advertised as a synthetic orchestra, and while we may still hear vast differences between the real thing and an organ stop, there are some interesting combinations possible that can enhance the orchestral texture. Carefully controlled use of an organ can inobtru-sively round-out the sound of the orchestra and add thrilling new colors, expecially at climax points. Again, watch the dynamic levels; the organ needn’t remind you of the Easter service at St. Patrick’s Cathedral.

Amplification

Never, you say? Not kosher? What about professional recording studios? They make excellent use of microphones, not just to increase the amplitude of sound, but to create fine balance and texture, and even add reverberation. In fact, miking and mixing can even produce some sounds that are not possible with ordinary doubling. There are so many fantastic electronic devices available today that we owe it to ourselves and our players to investigate every possibility. Better amplifiers don’t distort; they have superb quality, can help improve balance, and can produce some beautiful effects by feeding the source through mixing channels. Contact mics are available for all instruments, and synthesizers can imitate many instruments with uncanny realism as well as produce new and exciting sounds of their own. Let’s not overlook these technological possibilities for school groups.

Imaginative directors of course will think of many additional ways to make their groups sound better. The instrumentation that you have been complaining about is really not as much of a stumbling block as you may think. What is important is planning it so your group is capable of sounding good even before they start to play.