There are several major pieces for concert band that feature folk songs as the main melodic material. Beloved examples of this genre include Ralph Vaughan Williams Folk Song Suite, Percy Grainger’s Lincolnshire Posy, Gordon Jacobs’ William Byrd Suite, and Gustav Holst’s First Suite in Eb and Second Suite in F.

There are several major pieces for concert band that feature folk songs as the main melodic material. Beloved examples of this genre include Ralph Vaughan Williams Folk Song Suite, Percy Grainger’s Lincolnshire Posy, Gordon Jacobs’ William Byrd Suite, and Gustav Holst’s First Suite in Eb and Second Suite in F. At the beginning of the 20th century, British concert band literature largely consisted of popular music or transcriptions of orchestral music, rendering the concert band something of a second class musical citizen. Gustav Holst’s First Suite in Eb (1909) was one of the first original works for the concert band that helped define the concert band as an important musical medium. Holst wrote the Suite when he was 35 years old. The Second Suite was written two years later in 1911.

The First Suite was not commissioned by any particular group but was written to fit the mold of characteristic sounds of the typical British military band. The instrumentation of military bands was always in flux, because most of the bands were made up of players from local communities.

Neither suite became a part of the standard repertoire of bands, either in England or America, for many years. At first Holst published only a condensed score and set of parts. Because of this, there are some lingering questions regarding instrumentation. The flute part for the First Suite is marked Concert Flute and Piccolo (there is also an ad lib part marked 3rd Concert Flute in default of Eb clarinet in the Boosey & Hawkes Company 1921 edition). It is not indicated exactly where the piccolo is to double throughout the combined part; however, it seems clear that the piccolo should not double every single note that is written in the flute part.

Since Holst was not writing for any particular military band, it is possible he was leaving some instrumentation issues open to the discretion of those performing the work. Because the concert flute/piccolo part is written so that players of both instruments play from the same physical part, I believe this opens the door to various interpretation of the doubling. We might also consider Percy Grainger’s concept of bandistration where different colors and combinations are possible by way of playing or omitting various cues written in the parts. Again, this seems to encourage the idea of changing instrumentation to highlight strengths within a particular group. I can remember being asked to add piccolo at different places in the Holst suites over the years at the request of the conductor.

Frederick Fennell (1914-2004), founder of the Eastman Wind Ensemble, devoted his lifetime to the study, performance, and recording of wind band literature. In 2005 Fennell made a critical edition of the Holst First Suite in Eb and Second Suite in F which were published by Ludwig Masters. This score of the First Suite contains a reprint of an article written by Fennell about the work. The article was first published in The Instrumentalist magazine in 1975. Likewise the score of the Second Suite contains another reprint of an article also published in The Instrumentalist in 1977. Fennell’s artistic ideas on doubling seem to maximize tone color contrasts in the ensemble. In general, he asks the piccolo to play in the same octave as the flute when the overall sound desired is warmer, and in tutti passages, the flutes are doubled at the octave by the piccolo. This doubling adds a sheen to the overall sound of the group. Since folk songs are repetitive by nature, the instrumentation change often happens on a repeat of the melody which adds contrast and makes musical sense.

In the Fennell edition of both suites, a separate piccolo part has been published which clarifies the doubling issues. Fennell’s piccolo doubling choices are listed for each work below:

First Suite

Mvt. 1: (Chaconne) Piccolo plays doubling flute line bar 30-39, then again at bar 41, again in bar 112

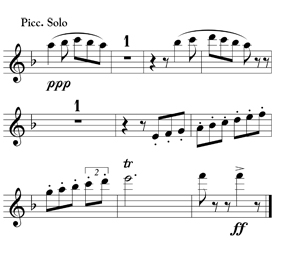

Mvt. 2: (Intermezzo) Piccolo enters at pickup to bar 151 thru bar 199, again at bar 241 until 272, doubling flute’s octaves, then plays a small solo at the close of the movement for half a measure.

Mvt. 3: (March) Piccolo doubles the entire length of the movement playing flute line, but plays in the lower octave in two measures which is specified in the part.

Second Suite

Mvt 1: (March) Piccolo doubles flute up to bar 19 (sounding in the same octave from bar 11), in at bar 23 sounding 8va. Bar 35: Piccolo doubles flute octaves through the rest of the work.

Mvt. 2: (Song Without Words, “I’ll Love my Love”) Piccolo doubles flute octave in bar 12-13, from beat four, bar 20, from beat four in bar 24-26 and from beat four in bar 28-30.

Mvt. 3: (Song of the Blacksmith) Piccolo doubles flutes at sounding octave.

Mvt. 4: (Fantasia on the “Dargason”) Piccolo doubles flute octave to bar 57, bar 72-121: same octave as flutes, bar 128-171 doubles flute sounding one octave higher, small solo from 202 to the end.

It seems Holst enjoyed the punctuation mark of a piccolo ending for a couple of the movements, including the half bar solo that ends the Intermezzo movement of the First Suite and the closing of the Second Suite.

When performing this solo, it is important to maintain strict rhythmic integrity and come in exactly on time. The piccolo is involved in a “call and response” pattern with the tuba that should sound humorous due to the register extremes presented. It helps to stress the first quarter notes in the pattern with a bit of vibrato (Note the tenuto stresses on the notes are from the Fennell edition and are not in the original parts. Fennell has also added the word lyrically to indicate the sweet nature of this solo, which is a terrific editorial suggestion).

Keep the articulated ascending staccato scale light and forward moving, taking care to play the duple rhythm in time. If you slow down at the end, this is not the correct musical intention. It is stylistically correct to add a termination on this trill (note that the Fennell version has it marked) and crescendo into the final F. I prefer using the triple tonguing pattern TKT, TKT all the way through the triplets due to the low register. This seems to speak more cleanly than the usual strict alternation of syllables TKT, KTK. I use single tonguing for the duplet.

Frederick Fennell’s ideas about the interpretation of the piccolo doublings are but one solution. As you perform this piece in different ensembles, it might be interesting to keep a diary of each conductor’s decisions.