In 1972 EMI recording company invited three young soloists, who had been successful in recent competitions, to record a tribute album to Henri Dutilleux. The soloists were Kathleen Chastain, flute; Yves Poucel, oboe; and Jacques Delannoy, piano. The LP was to include Dutilleux’s Sonatine for flute and piano, the Oboe Sonata, and the Piano Sonata, Op. 1. Only the piano sonata had been given an opus number because Dutilleux had not deemed the two woodwind “Morceaux de Concours” worthy of them.

In 1972 EMI recording company invited three young soloists, who had been successful in recent competitions, to record a tribute album to Henri Dutilleux. The soloists were Kathleen Chastain, flute; Yves Poucel, oboe; and Jacques Delannoy, piano. The LP was to include Dutilleux’s Sonatine for flute and piano, the Oboe Sonata, and the Piano Sonata, Op. 1. Only the piano sonata had been given an opus number because Dutilleux had not deemed the two woodwind “Morceaux de Concours” worthy of them. Chastain, who had been my student and later my wife, had graduated from Jean-Pierre Rampal’s Conservatoire class. She was to record the Sonatine. At the recording session she played the Sonatine twice through and the producer decided that it was fine. Everyone was looking forward to a successful LP of these previously unrecorded instrumental works.

Soon after the recording session Kathleen saw Dutilleux at a concert. She told him I was playing the Sonatine in Alice Tully Hall in New York City and she was recording the Sonatine in Paris. Dutilleux, whom Kathleen and I knew quite well, was unaware of the project and became quite upset. He thought he had done a poor job in composing the Oboe Sonata and the flute Sonatine and did not want either piece recorded. Dutilleux was currently working with EMI and Rostro-povitch on a recording of his Cello Concerto, so he called EMI to hold off the pressing of the LP.

Henri Dutilleux is like that. He is a very shy man who is extremely critical of himself, and even more adamant about the quality of his own work. So, to everyone’s disappointment, the record was put on hold. The Sonatine was eventually released much later in a CD called Flute Passion.

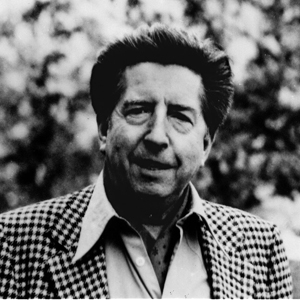

January 2012 marked the ninety-sixth birthday of Henri Dutilleux. He was born into an artistic family and raised in Douai, the same city as Gaston Crunelle. Dutilleux always complained that he was a slow worker, which accounts for his relatively small catalog. In addition to a love of painting (his great grandfather was the 19th century painter Constant Dutilleux), he is extremely sensitive to poetry, which explains the titles of many of his works.

He wrote most of his great pieces on commissions, many of them coming from orchestras in the United States. Métaboles (1964) was commissioned by the Cleveland Orchestra (George Szell, Music Director). It explores the transformation of a musical idea in a kind of Enigma Variations format but in a different stylistic context, of course.

Symphony #2 “Le Double” (1959) was commissioned by the Koussevitzky Foundation for the Boston Symphony (Charles Münch, Music Director). This symphony features a concertino group (one player from each section) in dialog with the larger symphony.

His main works for soloist and orchestra are the fruit of commissions by great players. Isaac Stern commissioned L’arbre des songes (The Tree of Dreams) (1985) for violin and symphony orchestra. Jean-Pierre Rampal practically begged Dutilleux to write a piece for flute and orchestra, but unfortunately it never came to fruition. The best commission was by Mstislav Rostropovitch, “Tout un monde lointain…absent, presque défunt” (1970), (A whole world far away… absent almost dead), for cello and large orchestra. I was then a member of the Orchestre de Paris and I have a vivid memory of the premiere. Ah! To be witness to such a great musical moment!

In my opinion, the Sonatine is still one of the best 20th century works for flute, but I perhaps can explain why Dutilleux dislikes the work. One of the perks of the Prix de Rome, which Dutilleux won on the eve of WWII, was to receive commissions for the Morceaux de Concours. The problem with this was that it was restrained by certain formal, age-old traditions. The composition must be approximately 8-10 minutes in length, have a fast movement, a slow one, some détaché, some legato, and a cadenza. The Sonatine had to be composed in a month, in total secrecy, and premiered at the Concours. Henri Dutilleux, the slow writer, was running short of time. That is why he chose to repeat the first cadenza a half-step higher. He told Monsieur Crunelle and me that he disliked this expedient. He said that during the month he always planned to work on the Sonatine, and he never got around to it. The version we have today dates from 1943 and contains a few errors.

There should be a very slight ritard before rehearsal 1, but none before rehearsal 3. In the finale, the scale in the 7th bar after 10 should be meno mosso. Finally, the last notes of the Sonatine, in spite of the written accents, are the culmination of the long final accelerando and should be given rush, not weight. No Brahms Symphony here!

The movement that Henri Dutilleux claims to like and would have reworked is the first one. He was, at 27, still influenced by his artistic and poetic family. He says he had in mind a Cubist painting, where lines and volumes create tension instead of sensual figures.

It is a mistake, in my view, to play the Sonatine like the Poulenc Sonata or even the Sancan Sonatine, with too much color change and rubato.

Home > Henri Dutilleux

Henri Dutilleux

SHARE THIS ARTICLE

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Michel Debost

Michel Debost is the former principal flutist of the Orchestre de Paris and flute professor at the Paris Conservatory and Oberlin Conservatory. He is the author of The Simple Flute.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

A Conversation with Linda Pulley

Five Tips for Guiding Student Arrangers

ADVERTISEMENT

Order your Marching and Color Guard Awards this Fall!

Orders may be placed through the online store, by email (awards@theinstrumentalist.com) or by calling 888-446-6888.