Alfredo Casella’s Sicilienne and Burlesque holds a unique place in the history of contest pieces written for the Paris Conservatoire’s annual concours for flute. The Italian Casella was a child piano prodigy. He went to Paris just before 1900 to study composition and remained in France for at least 15 years. His teacher was Gabriel Faure; Maurice Ravel was a fellow student whom Casella admired and later emulated. At the time Paris was the musical epicenter for most established or aspiring European and American composers, and Casella met and heard music by many great or future-great 20th-century musicians: Claude Debussy, Gustav Mahler, Richard Strauss, Rimsky-Korsakov, Bela Bartok, Arnold Schoenberg, and Igor Stravinsky.

In particular, Casella embraced Stravinsky after hearing the riotous premiere of The Rite of Spring in 1913. Casella’s early compositional influences from the French Impressionists gave way to Stravinksy’s more barbaric primitivism, and his former French elegance of line and Romantic harmonies suddenly acquired new expressive extremes.

Written in 1914, Sicilienne and Burlesque represents a strange combination of French Impressionism, early Italian forms, and the Stravinsky of Rite and Petroushka. The unorthodox piano writing is largely responsible for the strangeness, with haunting parallel chords, superimposed harmonies, marcato sequences featuring seconds and open 4ths and 5ths, and growling bass motifs that accentuate the piano’s percussive qualities (e.g. the Jaws half-step motif during the Burlesque). We will examine Sicilienne and Burlesque by looking separately at each ingredient of Casella’s multi-national recipe and then swirl it all together for a final analysis.

Italy and the Commedia Dell’Arte

Sicilienne and Burlesque follows the French contest-piece formula of a slow, lyrical opening followed by a fast and virtuosic section. Rather than using a common title, such as Fantasy, or two tempo-related markings (e.g. Andante and Scherzo), Casella used Italian forms to distinguish himself from his Paris colleagues. The siciliana/siciliano was a slow pastoral dance in 6/8, 9/8, or 12/8, characterized by the lilting dotted rhythm we see in the opening bars of the piece.

Starting innocently enough, the lilt escalates quickly into a powerful climb up to high B in the third line. This outburst at the top end of the scale is more reminiscent of Jolivet and Dutilleux, writing some 30 years later, than of Casella’s peers, such as Gaubert, Enesco, or Faure. The same can be said of the cascading section on the second page. Even without considering the somewhat dark and unsettling piano writing underneath, this Sicilienne goes far beyond its Italian origins in mood and beyond the Paris Conservatoire’s typical treatment of range and dynamics for competition pieces.

Starting innocently enough, the lilt escalates quickly into a powerful climb up to high B in the third line. This outburst at the top end of the scale is more reminiscent of Jolivet and Dutilleux, writing some 30 years later, than of Casella’s peers, such as Gaubert, Enesco, or Faure. The same can be said of the cascading section on the second page. Even without considering the somewhat dark and unsettling piano writing underneath, this Sicilienne goes far beyond its Italian origins in mood and beyond the Paris Conservatoire’s typical treatment of range and dynamics for competition pieces.

The burlesca is an Italian form that goes back to at least the 17th century and is related to the commedia dell’arte, a uniquely Italian brand of theater originating in the 16th century. The plays featured stock characters and parodies of serious universal themes (e.g. love, age vs. youth) that are changed into outlandish and distorted versions of themselves. In music, the burlesque became popular somewhat later; it too used both serious and comic elements that were juxtaposed to result in a skewed and grotesque effect.  As with the Sicilienne, Casella’s Burlesque delves into an emotional realm quite outside the contemporaneous flute repertoire’s Romanticism and Impressionism. We see this superficially on the page with dynamics routinely reaching double and triple forte and increasingly agitated Italian phrases during the movement: allegramente, brillante e con fuoco, scherzando giocoso, con forza, stridente, sempre piu vivace, con bravura, stringendo sempre piu.

As with the Sicilienne, Casella’s Burlesque delves into an emotional realm quite outside the contemporaneous flute repertoire’s Romanticism and Impressionism. We see this superficially on the page with dynamics routinely reaching double and triple forte and increasingly agitated Italian phrases during the movement: allegramente, brillante e con fuoco, scherzando giocoso, con forza, stridente, sempre piu vivace, con bravura, stringendo sempre piu.

The French Connection

Casella’s debt to Faure and his admiration for Ravel showed in his music throughout his career. During most of his sojurn in Paris, Casella’s music was clearly full of the French Impressionists’ style, and the early Barcarola e Scherzo (1903) for flute and piano fits naturally into the melodic and harmonic molds of our best-known French collection, Moyse’s Flute Music by French Composers.

The fact that Sicilienne and Burlesque is still part of the French style but significantly altered by Stravinsky’s influence presents a performance challenge for flutists: How much Ravel and Faure do we hear, and how much Petroushka and the eerie beginning of Rite? The very opening piano solo, for instance, is reminiscent of the bassoon solo that begins Stravinsky’s latter work. Without the piano, the flute’s first couple of entrances appear to be the typical siciliano pastoral mood; with piano, the tone takes on a murkier quality that lends uncertainty, a heavy suspense, to the languido e dolce that Casella asks for.

As the movement progresses, we are surprised again and again by harmonies that underlie the flute part, particularly in places where expressive directions and melodic figures suggest something quite different on the page. For example, on line 6 of the first page, the flute’s D-flat entrance is marked pp espressivo with a broad crescendo to the middle of the phrase, then back down to begin a section that breaks into a light and capricious figure (end of line 7 into 8). If this passage were, say, Taffanel’s, the D flat would likely be part of a D-flat or A-flat harmony, and the low Fs three and four bars later might represent F minor.

The entire passage from line 6 through line 8 strongly suggests A-flat major/F minor and D-flat major/B-flat minor. When the piano enters, however, anything remotely suggesting tonality is obliterated. In fact, the only link between piano and flute is the piano’s undulating rhythms of the siciliano, which persist throughout the section. So the flute’s high D flat actually enters as a pale, unearthly dissonance to what is happening below. We must find a tone color to match this mood, not the one we might want to hear in our heads from Taffanel.

For a brief moment, the harmonies on the second page, line 1 and into 2, suggest a Ravel-like lushness – even a trace of Hollywood – that match the intent of the flute line. But as soon as we reach the trills and cascades of runs, the piano reverts to stark parallel intervals used for driving the flute forward with tense energy. With more traditional French writing, this would be a moment to stretch the tempo and shape the runs. Here we feel no room to relax and instead must propel forward to the high F in line 3 (largamente), which should be an arrival but is in fact a higher level of tension. Casella confirms this by saying senza dim. as the line falls, sempre molto f as we go into the capricious figure from page 1, and senza Rall. at the final bar of the section – a written-out rallentando by way of increasing note values. Clearly, Casella wants the flutist to maintain high tension and discipline to the end.

We need less beauty and more power, a sound closer to Jolivet’s Chant de Linos than to any of Casella’s contemporaries who wrote flute chamber music. The orchestral Ravel of Bolero and La Valse and the large scores of Stravinsky come closest to conveying the scope of tone colors flutists should seek in this work. The end of Sicilienne dissolves to a haunting low register in the flute, made strange and without repose because the piano’s chords have nothing to do with the D-flat minor triad that is the flute’s sole material. Notice that Casella again writes in a rallentando in the last line by increasing note values; he does not want to give any expressive leeway even at the close. He finally drops down a half-step to C, which suggests the F minor connection in preparation for the F major coming up in the Burlesque.

France, Russia and Musical Cubism

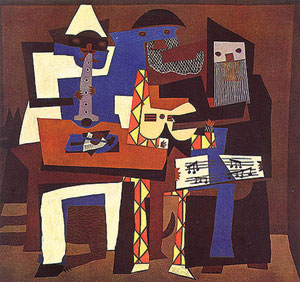

Casella has been referred to as a musical cubist during the period in which he wrote Sicilienne and Burlesque. Cubism is thought of primarily as a movement in visual art, with Picasso being its most famous representative.

A painting most musicians know is his Three Musicians, where we see three individuals playing instruments who are both interlocked and fragmented by geometric shapes. With cubism, the artist shows us many different angles or perspectives from which to view the work, rather than a linear and clear picture which the artist has imposed. In music, cubism exists when the composer presents a typical or expected form and manipulates it so that the listener is made to hear the work from several different and often conflicting points of view. This is exactly what Casella has done with Sicilienne and Burlesque: he has taken the familiar French Conservatory test piece and imbued it with the extreme expressionism of Stravinsky and the Ravel’s La Valse.

A painting most musicians know is his Three Musicians, where we see three individuals playing instruments who are both interlocked and fragmented by geometric shapes. With cubism, the artist shows us many different angles or perspectives from which to view the work, rather than a linear and clear picture which the artist has imposed. In music, cubism exists when the composer presents a typical or expected form and manipulates it so that the listener is made to hear the work from several different and often conflicting points of view. This is exactly what Casella has done with Sicilienne and Burlesque: he has taken the familiar French Conservatory test piece and imbued it with the extreme expressionism of Stravinsky and the Ravel’s La Valse.

The Burlesque, as mentioned earlier, is a musical form that exaggerates character and accentuates the bizarre. The flute writing features lots of marcato and staccato passages, along with exaggerated dynamics and abrupt shifts from aggressive to playful moods. The piano has brassy sounding chord clusters moving up or down in parallel motion, as well as high-register riffs sounding like top woodwinds that recall the opening market scene from Petroushka. There is also a more sinister-sounding, half-step theme in the piano’s low register that precedes the bravura staccato flute passages on pages 4 and 6.

The movement begins and ends solidly in F major and follows through with key changes when the main melody modulates (e.g. page 3, line 7: D-flat major; page 5, line 10: D major). The playful scherzando, giocoso theme also lands on key centers (page 3, line 8: C major; page 6, line 2: F major). In between these “French” areas, however, the listener is immersed in the more intense sound world of Stravinsky, which is represented in the piano’s clusters, riffs and growling bass motives.

Beginning with page 3, line 9, the piano sets up a low drum-like beat that goes to the last measure on page 4, line 4; the statements of the initial theme by the flute in this section have no harmonic basis, and the drum beat below changes the theme’s character to suspenseful and ominous. You may want to alter your sound to dark and hollow, with perhaps a more brittle articulation. These are options each player should address as the piano score becomes more familiar. Knowledge of the piano part in a duo work is always mandatory to create the most convincing performance. In this work the need to know the piano score is especially critical, given the combination of styles and perspectives that Casella presents.

From page 4 through the final return of the main theme (Giocoso) on page 5, the piano allows no tonal foundation. The pace becomes increasingly frenetic, and if you adhere to Casella’s markings starting with the first triple forte at the bottom of page 4 to Giocoso on page 5, the sound and articulation must keep intensifying all the way through. The only moments in the Burlesque that are not intense – the playful theme on pages 3 and 6 – should be performed with as much dynamic and textural contrast as you can muster. Playing this motive light and dry, thinking tongue in cheek, will add the bizarre edge to the music coming before and afterwards that Casella had in mind.

The Etudes

Finding etudes that address the technical problems of Sicilienne and Burlesque along with Casella’s heightened emotional demands was a challenge. Sigfrid Karg-Elert’s 30 Caprices, Op. 107 were written precisely during Casella’s compositional period, and they come from the same highly charged expressive world.

In Karg-Elert’s own words, from the Introduction to his Caprices:

“The 30 Caprices originated from the urgent need of forming a connecting link between the existing educational literature and the unusually complicated parts of modern orchestral works by Richard Strauss, Mahler, Bruckner, Reger, Pfitzner, Schillings, Schoenberg, Korngold, Schreker, Scriabin, and Stravinsky; . . .The Caprices explore new and untrodden paths in technique; a technique which may be required from one day to another in some new impressionistic or expressionistic work.”

Number 16, un poco mosso, umoristico, is helpful for the scherzando passages in both movements. Execute all the carrot accents in this etude, and you will have the context for Casella’s biting humor.

Number 20, Ardito, capriccioso ed assai mosso, is terrific for work on extreme and sudden character changes..jpg)

Most of the Italian terms are common or easy cognates (e.g. malizioso, umoristico). One you may have trouble with is loquace, which means loquacious or talkative. How to put this character into the music is a fascinating problem. You might think about a recitative kind of style, which allows for some rubato in the line. Whatever you decide, exaggerate the various characters to the fullest.

There are two Bach Studies that I find very effective support for several technical passages in Burlesque. Lines 2 and 3 on page 3, and the bottom of page 4 look surprisingly similar to Bach’s writing, as do the staccato bravura passages on pages 4 and 6. Etude #12, Prelude (for pages 3 and 4), and #24, Presto (for pages 4 and 6), are both from solo violin partitas and demand a more forceful or high-energy sound and articulations approximating a violin.  To play with this style through both etudes is exhausting and will definitely build embouchure endurance. Using transcriptions you will reach further than you would with one of Bach’s flute sonatas to play a kind of heightened Baroque that will take you closer to Casella’s music. If you think about playing his passages with the even, strong sound and finger technique, and the drive of Bach, you are well equipped to dig into Burlesque with great command of its technique and compelling tone throughout.

To play with this style through both etudes is exhausting and will definitely build embouchure endurance. Using transcriptions you will reach further than you would with one of Bach’s flute sonatas to play a kind of heightened Baroque that will take you closer to Casella’s music. If you think about playing his passages with the even, strong sound and finger technique, and the drive of Bach, you are well equipped to dig into Burlesque with great command of its technique and compelling tone throughout.

For the passages that modulate quickly with the same material or are stated in multiple keys (such as Burlesque’s main theme and section at the top of page 5, lines 1-3), Geoffrey Gilbert’s Sequences are helpful. In particular, #8 has some of the same contour of line as Casella’s passage on page 5, and it moves faster than other examples in the collection. Play it as fast as possible and slur everything if you want to simulate the passage in Casella.

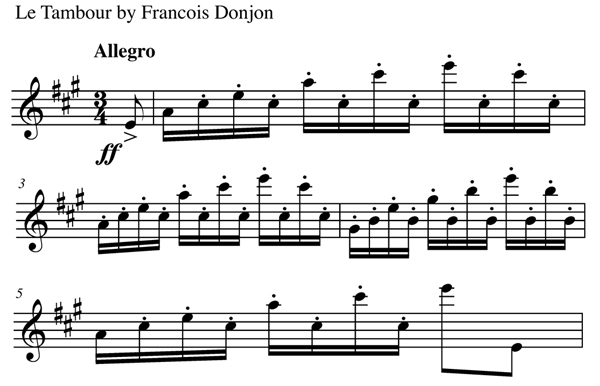

The last two etudes come from contrasting periods, but both help improve staccato articulation with uneven or widening intervals. One is from Donjon’s 8 Etudes de Salon, which is found in The Modern Flutist. Called Le Tambour [The Drum], its outer sections are a vigorous workout in broken chords that are marked (rather uncharacteristically) fortissimo. The other etude is #3, Pour le staccato from Douze Etudes by Marcel Bitsch.

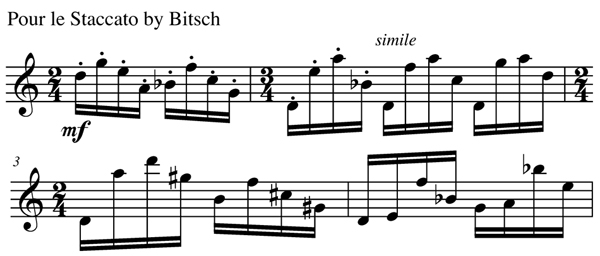

Called Le Tambour [The Drum], its outer sections are a vigorous workout in broken chords that are marked (rather uncharacteristically) fortissimo. The other etude is #3, Pour le staccato from Douze Etudes by Marcel Bitsch. This etude is wonderful for acquiring great embouchure flexibility while maintaining an even staccato.

This etude is wonderful for acquiring great embouchure flexibility while maintaining an even staccato.

At a time when our flute repertoire was firmly rooted in late-Romantic and early-Impressionist styles, Sicilienne and Burlesque offers a taste of the emerging Expressionist (using melodic or harmonic manipulation for expressive effect) manner. Casella’s multifaceted technique, which presented essences of the older styles at the same time as the new, offers us a true musical prism and a unique performing challenge. Sicilienne and Burlesque stood (and still stands) alone in our French concour pieces as a unique representative of its turbulent time.