When I was 18 years old, I switched from classical to jazz flute. I was told that beyond improvisation, the biggest difference between these two styles was the treatment of rhythm. This was confusing to me. Wasn’t rhythm the same? Isn’t a quarter note a quarter note regardless the style it is played in?

I completely missed the point of this exercise because all I could hear was the weight of his quarter notes, and how different they sounded from the ones I played. His were both mesmerizing and grounded.

For musicians who play melodic instruments, the idea of practicing rhythm can be elusive. Rhythm is generally thought of in terms of its relation to someone or something else. Playing with a metronome can feel sterile while playing without one leads to problems. My lesson with Teuber sent me on a quest to improve my rhythm.

Developing a Grounded Sense Of Time

Rhythm felt like an abstract concept that either you understood or you didn’t – and I just didn’t. On the advice of my teachers I started listening to recordings of myself and was surprised by how different my rhythmic phrasing sounded than I expected. My rhythms were not connecting at all. When I played with others, I floated above them. It made me feel like the music was going on beside and underneath me, and not around and within me.

I began listening for what interested me in music, and it always came back to the rhythm. This is what allow s players to breathe together in the music. When everyone feels the rhythm together, they create forward momentum and also land together.

Heartbeat

Think of the beat in music as a living thing just like one’s heartbeat, breath and pulse. Like a heartbeat, if you listen for it, you will hear it. However, if there are too many other sounds, it gets drowned out. Even when you cannot hear it, however, it is still there and quietly informs everything you do.

Metronomes

A common misconception about practicing with a metronome is that it will make you sound mechanical. Instead, consider the metronome a placekeeper to show where you are in relation to the beat. With each heartbeat, the heart moves the blood, and the continuous motion between the beats keeps us alive. In music, the flow between the beats is the life. A strong internal beat pushes music forward, giving it momentum and life. A weak beat can make music fall flat even when all other aspects are in place.

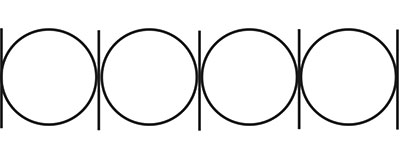

In the above illustration, imagine that the vertical straight lines are the beats and ticks of the metronome. All that space in between is what musicians should learn to control and manipulate as a first step toward rhythmic independence and a grounded sense of time.

In the following exercises move on only when the exercise is mastered, not just played correctly. Mastery in this context means it is easy to play correctly many times in a row. When you make an error, think about why you made it. The process of noticing and correcting these slips is what will improve your time feel and perception of the beat. Make sure you stay on each exercise until you no longer make errors before moving on.

When practicing scales with a metronome, the natural instinct is to put a click on every single beat. If done with careful intent, this can be very effective for improving precision, but it does nothing to improve time feel. If the metronome is ticking constantly, you do not have time to get off between each click and are able to rely on the metronome to keep the time rather than generating it yourself.

More Time between Clicks

The following exercises gradually increase the time between each click of the metronome without changing the tempo. This encourages players to keep some of the beats internally and grow a sense of an internal beat. The more space left between each click of the metronome, the more obvious the inconsistencies in your perception of time will become. This process will help with the concept of keeping tension on the time. This means that rhythm should have a feeling of tension and momentum. Imagine two people holding hands and leaning away from each other. If they completely trust each other and lean away with their full weight, the tension created holds them up with only the muscles in their hands being engaged.

Relating this to rhythm, consider that each person is a beat, and the hands holding them together are the time feel. Keeping the tension on the time is what holds everything together. The trust in this context is between the musicians and their instruments in relation to each other. If even one person lets go, we all fall.

When playing in an ensemble, trust is a big part of what can make it great. If one person is not holding their share but rather hanging in the others’ grip, it forces other ensemble members to carry that weight, and the rhythm feels uneven. When playing with this idea by yourself, treat the metronome as the other person. The metronome itself does not provide tension, but your relationship to it can create it. This sensation of tension is something musicians should relax into like the surface tension on a trampoline. Be very careful not to let it translate to physical tension in your body.

Taffanel et Gaubert, No. 4

Use this or your favorite scale pattern with the metronome set at quarter note = 60. The click begins on each beat as shown by the accent, and then gradually beats get removed to create more space. Play each version until you are fully comfortable in every key. Make sure you are exactly on the beat no matter how difficult the fingers are. Keep working until it is perfect. Record yourself and listen for your attack and how it lines up with the metronome. In doing this you will begin to notice which parts of the bar you tend to speed up or slow down at and can address that.

When you stop and start over, you are only working on starting the scale with good time. When you keep playing and adjusting as you go, you are improving your time overall. Both are important, but be clear with yourself on which one of these aspects you intend to practice.

As your success improves, try setting the metronome to every four and then eight bars. These drills will help you improve your internal rhythm, allow you to keep tension on the time, and generate a groove without anyone else playing. This can be done with any scale in any key and with any articulation. It is a fantastic way to integrate improving time into your practice routine no matter what you are working on. The most common reason for time slipping or feeling lost is being insecure with the notes you are playing. For lines to flow no matter what key you are in, you have to practice all of the keys.

Building this relationship to time is a long process. It goes beyond muscle memory and into an even more fundamental awareness within the music. You may spend 10 minutes a day for a month with the metronome on beat one of every bar, and that is perfectly fine. Every moment you spend with awareness on time is a moment well spent. It takes time to cultivate. Sometimes it comes easy, and sometimes it is hard. At the end of the day, it is a physical sensation of feeling at home in the way the rhythm sits around you. Once these concepts become internalized, all of your other musical attributes will shine brighter in any style of music.

Once you can execute this correctly, then remove the accents on beats 2 and 4.

Once you can execute this correctly, then remove the accents on beats 2 and 4.

Next try placing the metronome on beat 1 of every other bar. (The metronome is now clicking at 7.5 bpm.)