Compilations of Great Ideas and Advice From The Instrumentalist Archives

Room for Improvement

By Jeff Jarvis

April 1998

Jeff Jarvis is a trumpeter, composer, professor, and music publisher. He was co-owner of Kendor Music Publishing from 1985-2015

The rhythm section of a school jazz ensemble usually has the most room for improvement, perhaps because most directors played wind instruments and are reluctant to cope with the rhythm section problems. Secondary school rhythm players generally have a good concept of rock, funk, and Latin styles but have not developed a good swing style. Often changes in equipment and a better understanding of these styles can make a great difference.

The only thing more troubling than watching a jazz ensemble set up a synthesizer as a grand piano is wheeled off stage is the sound that follows. Even the best sampled piano sound on a synthesizer is less satisfying than a real piano. It is absurd to spend thousands of dollars trying to imitate the sound of the instrument they’ve just pushed to the side of the stage. I often write contemporary charts with a synthesizer part in addition to piano to enhance the overall sound. Either instrument can be effectively used on contemporary Latin, funk, or rock charts, but the piano is the best choice for swing, jazz waltz, and jazz ballad styles.

The pianist should provide chordal accompaniment with rhythmic, percussive comping patterns and lean, resonant voicings. Novice jazz pianists tend to overuse the sostenuto pedal, which reduces clarity, but the greatest deficiency in young pianists is voicing chords. If charts do not include suggested voicings, inexperienced players often simplify the chords and produce harmonic clashes. An aspiring jazz pianist who sees a C+7 and doesn’t understand anything beyond the letter name of the chord will simply play a C major triad. However, the natural fifth played against the ensemble’s augmented fifth will create an unpleasant dissonance. Some jazz piano books to assist jazz pianists includes Voicing by Frank Mantooth (Hal Leonard), The Jazz Piano Book by Mark Levine (Sher Music), and The Chord Voicing Handbook by Matt Harris and Jeff Jarvis (Kendor Music)

Aspiring jazz guitarists tend to use equipment, settings, and concepts better suited for rock music. For swing charts the pickup selector should be set to the neck pickup and the tone control to a medium setting. When comping in the swing style, guitarists should use a basic rhythmic pattern of down-strums on each beat with a slight emphasis on the even beats. The entire forearm should be used in the strumming motion, not just the wrist. Pressure on the strings should be released slightly between each strum, and up-strums should be used sparingly. When conflicts arise between pianists and guitarists, they should alternate comping roles, with one player using sustained chords or laying out while the other comps.

Novice jazz bassists often play with a boomy sound caused by too much bass response on the amplifier settings. Adding some mid-range and treble to the setting will improve definition and pulse. This alone can profoundly improve the band’s concept of time. An acoustic bass works well for most styles with the exception of rock and funk charts. Either an acoustic or electric bass can be used for most Latin styles. Bassists should always connect notes, especially to walking bass lines in swing charts, unless the composer calls for short articulations. A subtle emphasis on the even beats will help the group to swing.

Drummers unfamiliar with the swing concept tend to use the kit the same way they would on a funk or rock chart, where the bass and snare drums keep time. However, a heavy backbeat on the snare and loud quarter notes on the bass drum will bog down the feel on a swing tune. The solution to this problem is to firmly close the hi-hat on the even beats while playing a steady swing pattern on the ride cymbal. The snare and bass drum should be used only intermittently for emphasis and color.

Teaching Improv

By Clark Terry

April 1991

Clark Terry’s jazz career spanned more than 70 years. He was a trumpeter, educator, composer, and NEA Jazz Master and performed for eight U.S. presidents. His original compositions include over 200 jazz songs. He once made a memorable visit to the Instrumentalist offices.

I use the concept that the old-timers used. They knew that they could play a series of notes that they called the blue notes, which was the tonic, minor third, and the flatted fifth. They didn’t know whether these notes had names, and they didn’t care. If you can find those blue notes from any given note on your horn, you can play with the greatest rhythm section in the world. You’d be suprised what you can do with those three notes. I tell the kids at my jazz camps that anybody who plays anything other than these three notes owes me a quarter. This immediately instills in them the discipline that is necessary to play jazz.

After they are restricted to those few notes they see how a blues scale fits together. Beginners are told to listen, but if a kid sits down with Coltrane records, it doesn’t get them anywhere. Kids should learn the basics. It’s like building a house, the deeper you dig the foundation, the higher up you can go. Beginners have trouble with an eighth note followed by quarter notes. The longer the phrase, the faster they play it. It’s like a runaway train. I try to teach them to lay back and get the true jazz feeling.

Musical Peaks and Valleys

By Maynard Ferguson

February 1986

Trumpeter Maynard Ferguson came to prominence in Stan Kenton’s orchestra before forming his own band in 1957. His groups often included rising jazz talent.

When you go through different stages of playing, I think you have to stay on the middle path and accept what’s happening. Eventually it will become the positive path and be good for you. If you have to take ten steps backwards because you’re going to have braces on your teeth, look at it as if you’re lucky because you’re getting something corrected…. When you’re in a valley, leave the drama to Broadway, Hollywood, and Bombay, and don’t allow your brain to make a drama out of something that goes wrong.

I like what I do in life because I love it. I think students should play an instrument because they want to play, not so they will come in first in a competition. Anytime you hear a person do something incredibly beautiful on an instrument, you should love that person and what you just heard. If you think competitively, you do yourself a terrible disservice. I admit my non-competitive thinking doesn’t always work in America school systems, where we’re looking for budget for another teacher or better equipment. Coming home with a plaque or medal can make things a lot easier for the music educator.

There is something about being competitive that I feel is thankless. It has never been anything but a joy for me to hear any of the great players like Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis, Freddie Hubbard, or Wynton Marsalis. They are all a joy to me. I enjoy listening to them and playing with them, and at the same time I know they don’t want to sound like Maynard Ferguson. There is only one Maynard. There is also only one Bud Herseth. That is an important part of my teaching. What comes out of the horn comes out of your own mind, your own disciplines, and your own habits.

Teaching

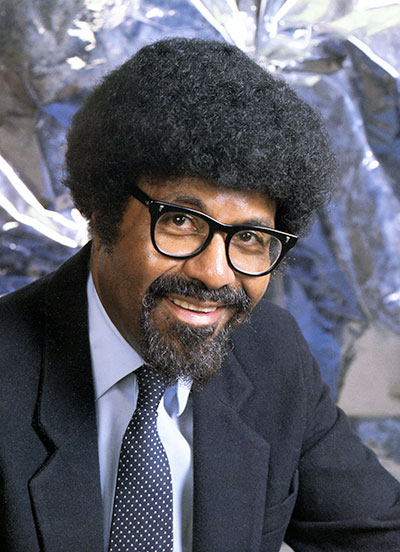

By David Baker

December 1986

David Baker was a jazz composer, conductor, musician, and professor of jazz studies at the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music.

Teaching requires constant renewal. I’ve never been able to understand teachers who can use the same syllabus year after year, as though new information does not exist. People say, “Why do you continue revising a music history class? History doesn’t change.” I say to them that our perceptions of history change. Things that formerly were seen as footnotes to a period in history may emerge as major epochs. The opposite is also true. Because of our proximity to certain events, they may seem important. Ten years later, it may turn out that these things weren’t important at all.

Focus on the Basics

By Bob Lark

October 2008

Bob Lark is a widely recognized educator and performer and was Director of Jazz Studies at DePaul University for more than three decades.

During the early fall rehearsals, I often take all of the toys away from the drummer except the ride cymbal, hi-hat, and the snare drum. This forces the drummer to concentrate on what is important, instead of adding a variety of nuances. This works great with student ensembles, and I will even do this with graduate students. The most important skill for any drummer to learn is timekeeping, and this is true whether the music is a swing chart, samba, rock tune, or ballad. On the snare drum, the left hand can subdivide important figures to guide the horns if necessary.

At the outset, I want to train the drummer and band to listen to and think about how the time is kept. It helps the drummer to focus on the basics if there are fewer equipment choices. With junior high drummers, this works remarkably well. I may restrict the drummer to playing a simple pattern with the right hand on the ride cymbal and have the hi-hat close on beats 2 and 4. In my experience, many drummers feel that they need to use all of the drums on an eight-piece set. Many can’t handle this without changing the pulse. At first, drummers may claim that they can’t play with just three instruments, but they can. Gradually, I let the drummer earn the entire drum kit, one drum at a time. I explain that it is like a stew: the other drums add flavor, but the essential ingredients are the three pieces of equipment they start with.

When working as a guest director, I may say, “I bet your drummer gets yelled at by your director more than anybody else in the band.” Usually there is a round of chuckling until I remind them that this is because the drummer is the most important person in the band. My technique of taking instruments away forces the drummer to focus on the basics.

Directing a Jazz Ensemble

By Bob Mintzer

July 1998

Bob Mintzer is a saxophonist, arranger, educator living in Los Angeles. He is currently holds an endowed chair at the USC Thornton School of Music and is a 30-year member of the Yellowjackets.

Good rehearsal techniques can help students develop the skills to play in an ensemble, including learning as a group to prepare music for a performance. I like to take difficult spots in a chart and dissect them, slowing down the tempo and having the musicians play the melody and accompaniment one at a time, so that everybody has a clear idea of what is going on. It is essential that everyone knows who is playing the primary melodic material and who is playing the accompaniment.

When things begin to jell rhythmically, I start to work on blend and phrasing. A good thing to do is to take a tutti passage for the brass and have them play without the rhythm section at a tempo much slower than the marked tempo. You can even begin with the first chord alone. See to it that everyone is aware of who is playing the lead voice and remind students that if anyone can’t hear that person, they should know that they are playing too loudly. Try to tune and balance the first chord until you can hear the chord ring. You will know when it is right. You may need to stop several times in a piece to do this when intonation and balance seem wrong. Once the blend is right, take a short phrase and have the band play, listening so they hear how it should sound. Make sure everyone is playing under the lead voice and that they are phrasing with the lead player.

Straight Ahead with Sammy Nestico

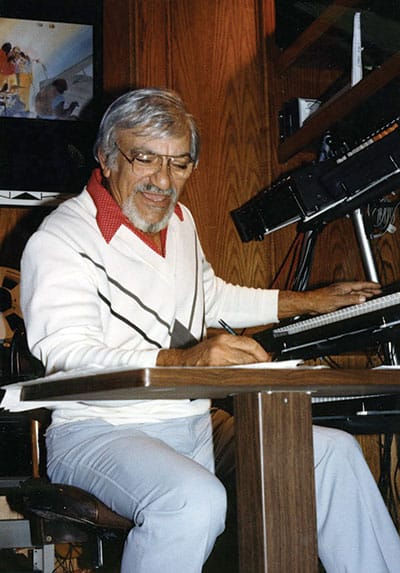

By Jim Warrick

February 1989

Sammy Nestico’s music has been played by countless jazz players. He published more than 600 arrangements for school band programs.

[A] musical highlight was when he started to publish his own music. “My first publications were watered-down arrangements of my Basie charts. In those days Art Dedrick was the father of stage bands, and he was just starting Kendor Music. I’ve always regretted that we simplified the first Basie charts I published. We just figured they were too hard for kids. In fact, we didn’t even publish Magic Flea for quite a while, and I think it sold more than any of the others when we finally published the recorded version.”

Speaking of his current success as a published composer, Sammy says, “I’m very proud to be writing for the schools of America. I think that’s terrific. There is something exciting about being able to write simple and melodic, but not bland pieces. It’s a challenge and a thrill to write something that you know has some musicality to it and yet is playable by young people. I’ll come out of my little studio and tell Margie that I really enjoyed that a lot more than writing a professional arrangement. A lot of love goes into the music I write for kids.”

When Sammy writes for publishing companies he feels added pressure to get it right the first time. “My schedule in Los Angeles never gives me time to hear school groups play my music. It’s almost always the publisher’s promotional record that gives me my first hearing of my music, and then it’s usually only 32 bars before it fades out. As I write I can hear the band in my head, but there are a few things that surprise me when I finally hear my music played by a band.

Sammy tries to write music that musicians will want to play. “Their enthusiasm for my music will spill over into the audience and the audience will like it. I like to write a piece that has everybody smiling after they hear it. I’m a happy person, and I like to write happy music. I guess that’s why I don’t write many minor key things.” When asked to name his favorite big band compositions or arrangements, he names Warm Breeze, Basie Straight Ahead, 88 Basie Street, Satin Doll, and Sweet Georgia Brown.

Reflections

By Jamey Aebersold

January 2018

Jamey Aebersold is an internationally-known saxophonist and authority on jazz education and improvisation.

Improvising Without Fear

Improvising can be scary, and we should dispel the myth that someone might not have the ability to improvise. One way to do that is to put students in a situation where they start out playing just on a scale. They need to develop confidence. The reason for the emphasis on practicing scales and chords, as well as learning melodies like Perdido or Satin Doll and numerous blues in the keys of Bb and F is that these are part of the basic jazz repertoire. Everybody has to do this sooner or later. If you wait until later, that probably means that you wasted a lot of time earlier just beating around in the bush and trying to find something that sounded good or impressed others.

If all students were taught to improvise as they come up through school, I guarantee that musical instrument companies would love it. People would graduate from school and continue to play their instruments and not retire them because they know how to improvise. They could play anywhere just for the enjoyment. Some do continue, but I would bet that the 98% who did not learn to improvise, never play music anymore after graduation. They listen to it, but they don’t play it. That’s sad.

The ego plays a part in this, too. It does not want you to sound bad. Once you start improvising the ego does not want you to play wrong notes, get lost, and stop at the wrong time. Nothing could be worse. The ego will discourage people from signing up for jazz band due to the unknown.

The Initial Breakthrough

When I was a 21-year-old teacher in Seymour, Indiana, I had a flute player with a great sound and great technique. One day we had ten minutes left in her lesson, so I asked her to improvise on a D minor scale over two octaves. There was a little piano in the practice room, so I played a walking bass line and chords in that key and told her to play whatever she wanted to play. I had never asked anybody to do this before. Right away I realized she was playing nice two-bar phrases, which she was imagining in her head. We did that for a couple of minutes, and I stopped and said, “let’s go up a half step.” We went to Eb dorian. I had her play the scale two octaves, then we tried improv again, and she did just great. We came back down to D minor and played it again, this time with the chord progression from So What. That’s what got me started – a young girl who could improvise with nice phrases without ever having done it before. She didn’t have a stack of records like jazz players do and hadn’t heard jazz before. That made me wonder if everyone could do this.

The Sounds in Your Head

I discovered that if I sit at the piano and slowly play a random but logically flowing chord progression, anyone can sing a solo to go along with it. The voice is a magical instrument, and the mind can sing great solos if the tempo is not too fast and the chord progression is not difficult. I have done this many times and that’s where my “Anyone Can Improvise” words came from.

Once I was giving a clinic in New Hampshire. I asked for a volunteer to come up with their saxophone and try to play along with me while I played some random chords on the piano. The volunteer sounded awful. Then I asked him to grab the microphone and sing for me instead, and he sounded great. He included notes that with diligent practice might take three years to play on his instrument. It was very musical but he had no knowledge of scales or chords or jazz in general, but his musical mind knew. All of the other students applauded because it sounded like music. Unless someone is nervous, nine times out of ten people will sing a good solo. It made me a true believer in our inner musical mind. It’s the instrument that holds us back. An instrument cannot match what a person hears in the mind. While in the early stages of learning improvisation, that is just enough to make someone give up. The ego says, “I told you that you couldn’t do it.” However, the ego lies.