Excerpts from an Interview with Eugene Migliaro Corporon

Originally published: January 1994

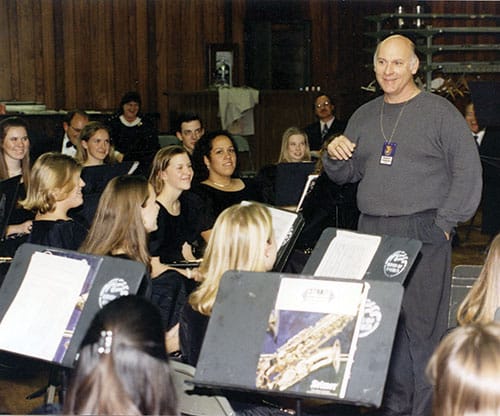

Eugene Corporon was already well-known when this interview appeared in the January 1994 issue. At the time he directed bands that the Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music and later became Conductor of the Wind Symphony and Regent Professor of Music at the University of North Texas. His groups have released more than 150 recordings.

Courtesy of Bands of America, Inc. and Jolesch Photography

What aspects of musical performance should students learn in high school?

Listening is the most important aspect directors can teach musicians at any performance level. In What to Listen for in Music, Aaron Copland defines performing as the act of converting listening into an audible representation of the piece. As musical symbols are turned into sound, poor performances are usually the result of individuals who are locked into their parts and do not listen to the group as a whole. Instrumental musicians play from one line parts, while choir members see the whole score, removing any doubt about who has the important material at all times. Consequently, the biggest challenge for instrumental instructors is teaching students how to listen to the other parts as well as their own.

Students should also know how a composer wanted the music to sound and make a performance correspond. The form and structure did not happen by chance. Composers convert an idea into rhythmic, melodic, and harmonic elements. When students understand this, the can recreate the original intent.

Finally, there is feeling. Music making is more than analyzing music and playing the right notes at the right time. That is making it right, not making music. Performers make music by using all of this information. When students say they have to miss rehearsal but know their part, I give a long philosophical discussion about how knowing the part is where rehearsals begin. Taking someone out of a combination of people who all know their parts takes away from the whole. Even with the best reason in the world for missing a rehearsal, the group is incomplete because one person is not there.

Is it possible for directors to be too serious in rehearsals?

I intentionally use the word play when referring to interaction with music. Like playing a game, it should be fun. This is important. Conductors sometimes are too serious. There is a dark side to intensity in which nobody has fun because the musicians fear making a mistake. Sometimes older musicians are afraid to show enthusiasm. There is often a diminuendo in enthusiasm with age. Think about beginners as they learn to play notes. They are enthusiastic and cannot wait to take their instruments out. Somewhere between this stage and adulthood, we become afraid to share our enthusiasm. I’ve talked backstage with musicians who have looked at me deadpan and said, “Boy, this is so exciting.” They are being careful not to appear overly zealous. Older students mistakenly think that this is part of becoming a professional player.

I would prefer students to emulate Barry Green, principal bass of the Cincinnati Symphony. He gets as excited about music as a 12-year-old. When asked about his enthusiasm over playing the Beethoven 5th Symphony for the 200th time, he mentions that the hall is a little different or he is different or the conductor is different, so no two performances are ever the same. Each recreation is unique. That’s the kind of model music students should have: people excited about music.

How do you keep rehearsals moving at a fast pace and avoid becoming too serious?

Rehearsals are my favorite part of making music. The goal is to understand and express ideas and feelings in the music. The director’s job is much like an archaeologist on a huge dig, who variously uses a bulldozer, a shovel, and sometimes a very fine brush. Musicians should understand the differences between short and long, loud and soft, and fast and slow.

I try not to let a rehearsal become bogged down by problems. Although there is much to be done, everything cannot be corrected at once. Remember that students are in band to play, not to hear the director talk. Offering a quick solution to a problem spot is always more effective than bringing a rehearsal to a screeching halt. Directors should identify the problem, offer a solution and move on. In addition to paying attention to the problem at hand, it is important to monitor those who are not playing. They will let you know how much time to spend. While you may not be able to correct a problem fully, at least you can outline a method for practicing the trouble spot.

Rehearsals should be serious, focused, and fun. There is nothing wrong with being serious. I use an hourglass approach when rehearsing: large sections, specific phrases, and large sections. This guides my analysis and rehearsal plan. Directors should take a piece apart and put it back together quickly. Students need to experience success in every rehearsal. Keep changing the focus and use the zoom.