Note-grouping is a phrasing technique in which the performer groups or clusters several notes together to express or enhance a musical idea or gesture. Note-grouping was first taught at the Curtis Institute of Music by professors William Kincaid (1895-1967) and Marcel Tabuteau (1887-1966). My first exposure to note-grouping came from flute professor Frances Blaisdell at the National Music Camp (now Interlochen Arts Camp) She was primarily a student of Georges Barrère, but had additional training with William Kincaid. In one of my first lessons, she asked me to play by memory a two-octave scale, with four sixteenth notes per pulse, slurred. Like most band-trained students, I accented the first note of each of the four sixteenth notes staying exactly in time with the metronome. My scale sounded plodding at best.

After I played, she sang a two-octave scale with these words: “I, am going home, to take a bath, to wash the car, to eat some food, to watch T-V, to feed the bird, to walk the dog.” Then she had me play the scale while she sang these words. We continued this duet until we had circled through all of the major scales using this note-grouping concept. Of course, when singing, she made octave adjustments here and there so the notes of the scale fit the range of her lovely voice.

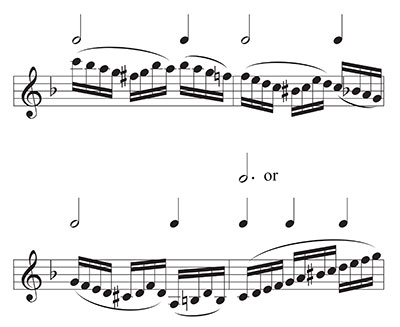

Next, Blaisdell wrote out a two-octave scale on a piece of manuscript paper. She told me that the first note was called a solitaire, and the next notes were played in the grouping of 2,3,4,1. Above these notes she wrote a small bracket. She said these brackets were think marks and did not affect the articulation or rhythms of the printed music. These groups were more energy marks. I later learned that oboe professor A.M.R. Barret expressed very similar ideas in his writing “On Expression” in his Oboe Method. He refers to the groupings as playing with nuance.

.jpg)

To help me master note-grouping, she played the solitaire note and then I played the 2341, and we continued alternating throughout the scale with her playing one group of 2341 and me playing the following 2341 ping-pong style. She encouraged me to be as sing-songy as possible in order to learn to feel the notes leading into the 1.

When teaching this in a band setting, use a 9-note scale (F, G A Bb C, D E F G, F E D C, Bb A G F). Play slurred. The first note should be played with resonance remembering that the strongest part of a note is at the beginning. Then there is a silence to be sure all students are in the same place. Begin softly on the G making a slight crescendo or a slight bit of energy with the air stream into the next notes. Place a small silence again between each group of notes. Repeat on the D E F G group, the F E D C, and finally the Bb A G F group. Repeat this several times. As the term progresses, a good goal is to be able to play this grouping on all 12 major scales. Once mastered, play without the silences.

When teaching this, I found that saying 1, 2341, 2341 was cumbersome and looked for a name for this concept. I let the students vote, and we decided to call this phrasing grouping “forward flow” because the notes flow into 1. This term seems to be sticking as at conferences I now hear the words “forward flow.”

Two Gestures

In music there are two gestures: forward flow (see above) and down/up (strong/weak). The down/up gesture comes from the Renaissance (1450-1600) when composers of madrigals used the concept of text painting. In text painting the music echoes the dynamic of the words. For example: Sing-ing (loud, soft), Lov-ing, Dy-ing, May-ing. Baroque and Classic composers used this gesture frequently in their music. In the 1700s the Stamitz family of composers referred to these two-note gestures as a Mannheim sigh because they lived and worked in Mannheim.

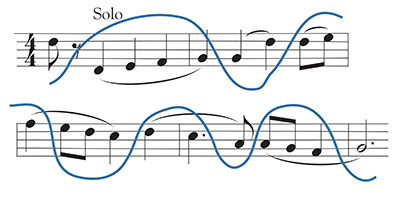

The A.M.R. Barret melody on the following page from The Flute Top Octave by Patricia George, published by Theodore Presser, illustrates this idea of two-note slurs or the two-note (down/up) phrasing gesture. See measures 2, 4, 5, 6, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 (three two-note slurs), (repeated in 15 and 16), 18, 20, and 22 for two-note gestures. Have students play just these measures with the second note softer than the first. My students are always amazed that once they find the two-note slurs, they have a phrasing plan for 15 measures of a 24-measure melody.

A.M.R. Barret melody

.jpg)

A good activity is to have students place an asterisk over each two-note slur in one of their band pieces and to practice those two-note slurs until they can always make the gesture strong/

weak or loud/soft. The duration of either note may flucuate. Sometimes the down/up gesture will be two sixteenths, two eights, or a half-note and a quarter. The important thing to notice is the slur placement and play the second note softer than the first note of the slur.

When teaching the down/up gesture in a band setting, use a 9-note scale (F, G A Bb C, D E F G, F E D C, Bb A G F). Play F, G, A, Bb pause, C D E F pause, G F E D pause, C Bb A G pause, F. Each group of four is slurred. The strongest note is the first of the group, and the following notes are played with a small diminuendo or decay. Repeat this several times.

As the term progresses, a good goal is to be able to play this grouping on all 12 major scales. Once mastered, play without the silences. Then alternate between the forward flow scales and the down/up scales. My students find that thinking of either going to 1 or coming from 1 is concise and helpful.

Another Way to Understand

Note-Grouping

My flute professor at the Eastman School of Music was Joseph Mariano (1911-2007) who was also a Kincaid student. Mariano added to the grouping concept and said that wind players should play as if the music was bowed (as in string technique). He told me that when playing in orchestra, I should pay attention to the concertmaster and follow the bowings. I realized that I knew little about string bowing, so I enrolled in a year-long MusEd violin methods class taught by David van Hoesen, an author of several string method books. I learned that the bow moves in two ways – down bow and up bow. A down bow starts with the right hand close to the player’s nose, and the up bow starts at the tip with the right hand away from the player. Generally, notes to be taken down bow start on the beat, and notes to be taken up bow start off the beat. Due to the construction of the modern bow, down bow notes naturally become softer as the right hand moves farther away from the player, and up bow notes naturally become louder as the player’s right hand comes closer to the player.

.jpg)

After taking this course and discussing my findings with Mariano, I began to mark my music with the down and up bow icons. From my violin studies, I realized that I could take many notes on a down or up bow, not just 2341 as in the example above. See the example below for forward flow and down/up groupings. When there are many forward flow groupings, I suggest students move about a ½ inch forward (VF) and then back (VB). For oboe and clarinet, moving slightly from side to side is a good way to practice this gesture.

24 Progressive Studies for the Flute by Joachim Andersen, Op. 33

.jpg)

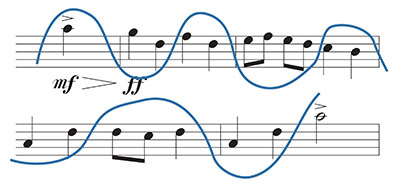

The Gustav Holst First Suite for Military Band, Op. 28, No. 1 provides some clear-cut exercises for note-grouping. The first movement begins with a chaconne that is repeated throughout the movement. I have marked the note-groupings using the scallops. I find using the scallops keeps the air stream moving more than the brackets. You can experiment with your students to find which method is most effective for you. One of the grouping rules is that notes of shorter value lead to notes of longer value.

.jpg)

In this next example at letter A, the notes of shorter value lead to notes of longer value. There is a crescendo until the third bar, and at that point the strength of the beat rule should prevail. That is, the first beat is the loudest, the second beat less strong, and the third beat the weakest. Often in the passage, a group will play beat 3 stronger than the opening beat of the measure.

.jpg)

In the following example, the rule of the strength of the beats comes from the rhythmic modes of the 1300s. The first measure implies a half note followed by a quarter (with figuration) or a long, short in poetry scanning. The player should show this inflection.

Letter B

Intermezzo, Movement 2

This is an excellent example of forward flow beginning with the opening 2, 3, 4, 1.

Tempo di Marcia, Movement 3

This is an excellent example of dancing or marching music. The down/up gesture is present. The strength of the beat should be followed.

As you work with these ideas personally or with your students, remember two wonderful quotations from cellist Pablo Casals, “the art of interpretation is not to play what is written” and “the heart of the melody can never be put down on paper.”