The left hand can be mysterious and confounding, especially to young and inexperienced conductors. Many wonder how to use the left hand effectively and where to place it when it is not active. Students are often taught not to mirror the right hand with the left hand too frequently. Its primary purposes, instead, are cuing and dynamics. Mirroring serves too narrow a purpose and shows an interdependence between the hands that will not serve a conductor well. This article offers suggestions about using the left hand as an effective tool for all conductors. The first step is understanding left-hand cuing and dynamics.

Cuing

The most common left-hand cue is the point, where a conductor uses the index finger or the hand in a downward motion to indicate an entrance. It is often done above the beat plane to emphasize the gesture and primarily when signaling soloists or small groups. This can be a personal and affecting gesture, but can also lead to traffic cop conducting, where the conductor is a facilitator for the players. A conductor can become a tool for the players instead of being a collaborator. In the same vein, I sometimes remind players that I am not their metronome; the tempo and time are carried within the group by each performer.

Conductors are artistic conveyors of musical intent and cuing should be approached in that spirit. Use functional gestures only when needed by the ensemble and not as a habit for all entrances. An effective cue creates an indelible bond between the conductor and player and serves as more than a rote reminder of a particular musical moment.

Cues are most effective when coupled with two complementary gestures: eye contact and breathing. Cues utilizing these two gestures create powerful and sympathetic connections with performers, regardless of the participation of the left hand. Players – especially soloists – seek reassurance of their counting and confidence in their entrances, something eye contact provides. Breathing heightens the connection between conductor and players, similar to preparatory gestures. In addition, the baton hand can be used to cue with a pattern by employing a sharp wrist gesture, elevating the hand above a normal rebound, and exposing the palm of the hand then utilizing a downbeat appropriate to the style of the music. For example, if a conductor wishes to give a solo cue on beat one of a measure, an effective procedure is:

1. Make eye contact with the player at least one measure before the cue, depending on the tempo, time signature, and importance of the entrance.

2. Convey style and anticipation through facial expression as the entrance nears.

3. Inhale a stylistically appropriate preparatory breath; at the same time, bring the wrist up beyond the normal pattern, exposing the hands and wrist to the ensemble in order to elevate the baton.

4. Expel air and relax the facial expression once the player has entered and is successfully performing.

5. Bring the pattern back down to the beat plane.

The left hand, in this case, can be used to reinforce the process, or not at all.

Using the Left Hand in Cuing

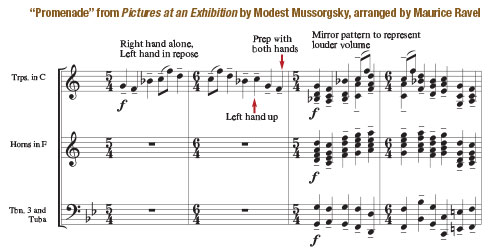

Left-hand cues are best used with broader entrances, within the pattern, and in conjunction with the right hand. An example of this is the brass sections’ entrance following the trumpet solo in the “Promenade” to Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition, arranged by Maurice Ravel. The trumpet solo in the first two measures should be conducted with the right hand only and with a small pattern (because, as I tell my students, one player does not need a conductor). Once the soloist begins, eye contact should be established with the brass sections, the left hand raises in anticipation of their entrance, and both hands are engaged on the preparatory gesture going into measure 3. The left hand effectively doubles the size of the pattern, corresponding with the expansion of the sound from a single player to an entire instrumental choir. The left hand disengages at the re-entrance of the trumpet solo as the conductor anticipates the next brass choir entrance and subsequent use of the left hand.

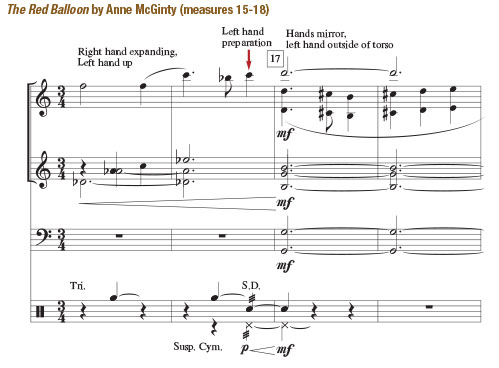

An example for younger players occurs in The Red Balloon by Anne McGinty, shown below. Measures 15 and 16 feature a woodwind and percussion crescendo that starts at p and culminates at measure 17 where the tutti ensemble enters at mf. It is tempting to use the left hand to indicate the crescendo; however, it may be more effective at measure 17 followed by mirroring the more expansive right hand. Its purpose here is to give a visual interpretation of the broadened style of the music. The left hand mirrors outside of the torso as the right hand functions normally, and the distance between the hands represents the breadth of the section. The left hand may disengage at the trumpet solo at measure 25 or show the sustained alto and bass lines by keeping it raised, hand in a relaxed position, no longer mirroring.

Another effective application is cuing the back rows of the ensemble. I often use my left hand to bypass the woodwinds for a brass or percussion cue. This is done when the back row players enter while the woodwinds are already playing. An example of this kind of cue happens in Festivo by Edward Gregson. In the coda of the work, the high woodwinds and percussion play overlapping ostinatos, and the saxophones and brass enter in the third measure. In this instance, the left hand is raised above the right hand in an open position to emphasize the entering half notes. Again, the cue begins with eye contact to the entering instruments.

Dynamics

Dynamics are often approached with a hand ascending to show an increase in volume, descending a decrease. In fact, another approach to dynamics is preferable, as will be described later. The palm should face upward when conducting in a stationary position only and not moving. It is challenging to create tension without discomfort when the palm is up. (Having the palm up and fully rotated causes tension in the elbow and forearm.) The palm-up gesture is better used to indicate sustain.

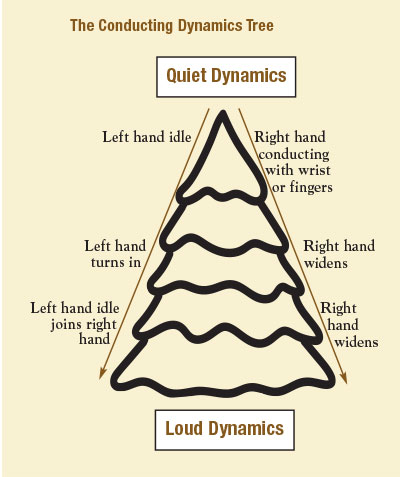

To use the left hand appropriately for dynamics, picture a Christmas tree: the quiet dynamics are at the top of the tree and inward, with the hands expanding down and out as the volume increases. The left hand can aid in this expansion. For example, at the quietest dynamics, the left hand can be idle at one’s side or used as a stationary indication of the subdued volume, resting in a relaxed position (palm forward) next to the right hand. In addition to indicating quiet, it also restricts the size of the right hand pattern. When intensifying the volume, the right hand descends and the beat pattern widens. The left hand then may become more active, initially turning inward and then mirroring the right hand.

The left hand can also prove effective for illustrating sudden dynamic changes. A subito accent becomes more powerful with a downward striking gesture, regardless of where in the pattern the accent falls. While I do not recommend an up and down gesture for dynamic contrast, the left hand smoothly descending (palm to the side, moving toward the body as it descends) can help diminish the intensity of the music. Note that the palm does not face down during this gesture.

Musical Style

The left hand can also indicate style. A stationary left hand in a specific shape can convey a mood or dynamic. Two examples are the gently cupped hand and the Italian O. A hand that is cupped naturally and raised slightly above the beat plane indicates a gentler, more relaxed style (e.g., the trumpet solo in movement 2 of Lincolnshire Posy). The Italian O is created by the touching the thumb and middle finger (or forefinger) of the left hand, creating a focal point at the connection point and a circle with the fingers. This gesture signifies precision, and the entrance is emphasized with a release of the connection between the fingers. It was taught to me by Anthony Maiello at George Mason University, who had a painting in his office of Arturo Toscanini executing that gesture.

Final Thought

There are myriad other uses for the left hand that convey musical style and meaning, and each conductor can identify the gestures that augment their approach to rehearsal and performance. It is fine to offer a cue or dynamics with the left hand, so long as that is not its sole function. Conductors collaborate with performers at every level, and they guide a journey of artistic discovery. The left hand can facilitate such interactions far merely signaling entrances and dynamic changes.