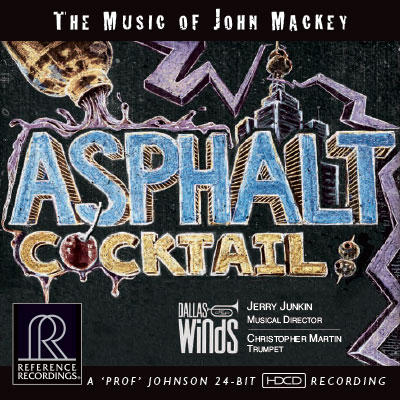

When Dallas Winds conductor Jerry Junkin and composer John Mackey met in Dallas last summer to record a full album of Mackey’s music, it was a reunion of collaborators and friends. Junkin has been a long-time proponent of Mackey’s music, and the Dallas Winds wanted to document its full range. Fellow travelers on this journey included New York Philharmonic principal trumpet Chris Martin, University of Colorado Director of Bands Don McKinney as producer, and the veteran recording team from Reference Recordings, assembled by Dallas Winds Executive Director Kim Campbell. The result is Asphalt Cocktail, a 12-track album to be released this fall. In the midst of the recording sessions, Junkin and Mackey paused to discuss the project and their musical partnership.

John Mackey, Dallas Winds Founder and Executive Director Kim Campbell, and Jerry Junkin take a break during a rehearsal for the recording session.

What are your musical goals for this recording?

Jerry Junkin: I have wanted to record an all-John Mackey CD for a long time. Everybody loves John’s music, but some people have a narrow view of his work, and his palette is wider and more diverse than they realize. I wanted this recording to show that. I wanted to include the high-energy, loud, strong music that he does so well, but also the introspective, quiet intuitive pieces that are not what people think of first.

Who decides how many recordings the Dallas Winds make in a year?

Junkin: The realities of fundraising go beyond my artistic desire. Like any organization, half or less of our funding coming from ticket sales from our loyal subscriber base. Philanthropic support is one of the other sources of money. Because recording is an expensive proposition, we only make one recording a year. There was a four-year stretch when the economy was weak when we did not record at all. Now, we have hit a good stretch where we have been recording again. These projects are a collaboration between me, management of the Dallas Winds, and Reference Recordings. I first talked to one of the founders of Reference Recordings about making a John Mackey album ten years ago, back when he did not have enough band music to make an entire CD.

You have been working together pretty much since John started writing for concert band.

Junkin: I met him when everybody else did in Minneapolis at CBDNA, when Fran Richard (ASCAP) introduced John to the profession as someone we should all know.

John Mackey: I sent my piece Redline Tango to Jerry in about 2005, and he told me that he planned to program it. And then he didn’t. I thought, “he must hate the piece.” Then, once he programmed it, he wouldn’t stop doing it. Since then, we have worked on almost every piece I have done except Foundry, which is explicitly for middle school band.

Junkin: I thought about recording Foundry, as well as several of the easier pieces that deserve a professional recording, for this CD. There are so many middle school bands that play that piece. However, eighty minutes is the maximum on a CD. At a certain point you just have to put the double bar on it.

In the booth during the recording session. John Mackey makes notes (left), while Reference Recordings Technical Director/Recording Engineer Keith O. Johnson follows a score (right).

John, having become primarily a band composer and working with Jerry throughout that portion of your career, how has he influenced your decisions?

Mackey: As I write the more expressive slower pieces, I am aware of how Jerry interprets those. It appears in my head when I am writing. If I am writing something with a lot of neo-romantic rubato in it, which you don’t hear much in wind conducting, I hear that now in my mind because of Jerry. Over the years of working together, I will have an idea of the expressive potential of a piece. Often he will do so much more than I would have imagined.

Jerry, do you feel that your interpretation of his music is affected by knowing him pretty well?

Junkin: I’m sure it is. I do feel like I have an insight into how he’s thinking because he has told me. I am not a mind-reader. We have had many discussions about how he hears music and feels about it. By sharing these thoughts, we can collaborate even if he isn’t in the room. I am affected by our previous collaborations.

Mackey: Would you do any of the pieces differently if I wasn’t here this week?

Junkin: No. Absolutely not.

Mackey: Interesting. I think that’s true.

Junkin: I feel confident with my insights about how he may be thinking and hearing his music. With a composer I have not worked with, I am learning about them. John and I have never had major blowups about music. If there had been, I have enough confidence to say “John, I know how this goes more than you do, because I have done enough of your music to know. You just need to listen to this.” I wouldn’t necessarily feel confident about doing that with another composer. If John said to me, “Absolutely not! I am the composer and this is what I am thinking” then I would relent.

Jerry, does your friendship affect how you interpret his music?

Junkin: Hopefully, yeah. The notes are on the page, but that’s just a language. The music is in the back of the notes somehow, and that is what you have to get at as a conductor. It helps to know the composer and understand their thought process and how they hear music. Some composers I have worked with over the years become more concrete in their thinking as they write more music. They might say, “I said quarter note equals 63; it has to be 63.” That doesn’t happen with John.

Mackey: Maybe it should!

Junkin: His composing is influenced by music he listened to long before he ever knew anything about bands. His writing has an expressive quality that goes beyond the printed image on the score. I try to get into a composer’s head and soul. I want to determine how they are thinking and feeling.

Mackey: I will never forget the first read through of Wine-Dark Sea. I marked it at 84, and Jerry conducted it at about 40. I thought, “someone didn’t listen to the MIDI recording. Someone just decided what it is supposed to sound like.” I tried to push the tempo back up. When Jerry conducted it at the original tempo, it sounded clunky. I find that when I disagree on tempos, often I will end up relenting.

Mackey: There are recordings that happen without the composer there that turn out quite well. I think that would have happened here. I hope I can provide another set of ears to point out interpretations that are important that might have gotten lost in the shuffle. I think I am especially effective at listening to specific sounds that I want from the percussion. There are always lots of intonation issues that are getting dealt with by others in the recording booth, and percussion sometimes do not get the same attention. When I make a MIDI recording of a piece, I am very precise about how I want it to sound, how long a china cymbal is allowed to ring before it is choked. When I am at the recording, I can specify exactly the mallet I want to hear.

With tempos, I think Jerry will get those, but not everybody does. There are plenty of recordings of my work with simply the wrong tempos. If they had allowed me to be in the room for any rehearsal, I would have made suggestions about the right tempos for the recording. When I post music on my website, it has exactly the tempo I think is right. With my fast music, I believe my marked tempos are right. As I said before, the slow music has greater freedom of time.

If I have marked music at 176, I want it at 176. If I mark it at 56, by the time you get to that tempo, it could work best at 46 or 66. By being here, I can make sure that some tempos do not get too far away from what I had in mind.

Junkin: I have learned over time that when you are recording, you have to trust the people in the booth 100%. What I hear is not what they are hearing, especially in the Meyerson Symphony Center where the sound is big. I have no clarity whatsoever about the sound during the recording sessions. I have to rely on Don McKinney, who has extraordinary ears, and the other people in the booth. It is so helpful to have the composer here to point out when he cannot hear the percussion. Because of the mics out in the hall, the whole sound field is different from what I hear.

New York Philharmonic principal trumpet Chris Martin came to record your trumpet concerto for the album. What was it like to have such a great player attached to this project?

Mackey: The first time I heard him play the flugel music in the concerto, I was amazed. There is a reason he is regarded as one of the greatest trumpet players in the world today. I have been fortunate to have Joseph Alessi play my trombone concerto and Tim McAllister play my soprano sax concerto several times. There are parts of those pieces that are almost impossible. At times I think the soloists are about to make a mistake, but they don’t. These players have a skill for identifying a problem and making an adjustment in a millisecond without anyone hearing it. Chris Martin is a machine, an expressive machine, so I am excited to have a forever document of what he sounds like on this recording with a professional ensemble.

Junkin: It would be easy for a person of his stature not to go to the lengths he has to be here. I appreciate his participation very much. In the overall scheme of things, there are several audiences for this CD. Reference Recordings has a huge audiophile following. There are people who buy every recording Reference puts out regardless of the medium. That is one market. Then, there is the band community and fans of John Mackey. Chris Martin adds another layer to all of this.

John, you have eight years of your work on this album. How has your voice changed or stayed the same?

Mackey: I think I am a much more confident composer. I do not feel the need to prove anything with the volume of the music unless it is warranted. Around the time I wrote Asphalt Cocktail, I was excited about writing music with the maximum level of aggression. Back then, there were few pieces that had a constant visceral punch. That can be fun, but it can become almost cartoonish. Some people decided that style was what my music sounds like. “Oh, that’s the guy who writes the super-loud stuff with too many cymbals.”

I no longer feel like I need to write what I called at the time “Napoleonic testosterone” music. The more grown up and musical approach is to trust that I know how to do this without distracting you with a punch in the face on every down beat.

Jerry, what is your favorite Mackey piece?

Junkin: The easy answer is Wine-Dark Sea just because of my connection with it, but I like many of his pieces. Honestly, the first time I heard Asphalt Cocktail, I thought to myself, “I’m never doing that piece.” Then, I was forced into doing it at a band festival I conducted in Japan. Once I conducted the piece, I changed my mind. I am happy to do it now. I learned something along the way.

There’s a lot that’s going well. Obviously, Texas is what I know the best. I am continually impressed when I work with Texas high school bands. There are more good bands and band programs in Texas than ever, and music in the schools is viewed as culturally important. I know that there are parts of the country where it is a more difficult situation, but there are a lot of great things happening and almost everywhere I go.

What is the secret to success in Texas?

People see the value of music education. I won’t diminish the role that the Texas Music Educators’ Association has played in that, particularly Executive Director Robert Floyd. That group has been such a dynamic lobbying organization, and they have been politically active in the state. When the occasional bill comes before the state legislature that might hurt music education, the forces are rallied, and I think it’s been a terrific watchdog organization for the health of the arts. The lobbying part of that group has been great.

What changes about how you rehearse with ensembles at different ability levels?

I’m working with high school students at a band camp this entire week, and they are remarkable. In one week, the program will be Procession of the Nobles and all of Wine-Dark Sea, and they are doing beautifully! I don’t feel that I adjust my conducting at all, and I try to speak to the high schoolers as adults. I will say that, even though it is fast work, there are three hours of rehearsal a day, so rehearsal is not as focused. With the Dallas group or in Hong Kong, you just have to move quicker. Because I know those players, I trust them. They know I am not going to belabor a point. I’ve said it, I mentioned it, I’ve seen the heads nod and the pencils go to the page, so I know that the next day it’s going to be better. If it isn’t, then we address it, rather than just having supervised practice. That’s not going to work with professional musicians or with a mixture of talented undergrads and grad students like at UT.

What tips do you have for people who want to improve as conductors?

People ask me all the time at conducting workshops about common pitfalls I see. The answer is that people do not know their music well enough usually. It starts with that. So many people overestimate how well they know the score and underestimate how well you should know the score. So, know your score better. Second, watch conductors. We are all part of this amazing YouTube sensation right now where a person can go online and see so many people, watch what they do as conductors, and evaluate what things make them effective. What I find most interesting is to watch people rehearsing. If you respect a good conductor, would like to model them, and can possibly get to a rehearsal, you will learn more in that hour than in any other way.

How do you program concerts for any ensemble you might be conducting?

That is different for every group. The main purpose of giving a concert at the university is the experience that the students have. It is all about the students. At UT, I have to reserve one piece per concert for a grad student to conduct, plus I have soloists and visiting composers. During the season – we give seven concerts a year – there aren’t really that many pieces that I get to select that I just want to perform. We have commitments.

With the Dallas Winds, the soloist or the theme of the concert is more important. I try to start with a big piece, maybe a concerto with a soloist or a symphony, and build the program out from that. I try to make sure that the concert has a great start and a great end. The season in Dallas begins in September, so I have the program put together ten months in advance, because there has to be publicity, and tickets have to be sold. For UT, usually I try to have it completed by May for the following September.

What is a valuable lesson you have learned over your career?

It is important to be nice to people. I tell my conducting and wind ensemble students it is an important part of being musicians. Be nice to people. Be responsible. When you are supposed to be there, show up fifteen minutes early. Be prepared. Have everything that you need. Be nice to people while you’re there. That goes a long way, actually. One of the things I think I have learned is that I can’t know everything. I thought for a while that I was supposed to know everything, and then I realized that every day it seems like that elusive goal is further away. There is more to learn! I have accepted that I’m never going to get to the end of the web. There is always more, so all you can do is the best that you can. You try your hardest, you work hard. I’m in a fortunate situation in this job. I never have to set the alarm clock because I wake up before it would go off and I’m ready to get to work. I love the work and it’s true what they say: my work is my play.

I do not have go-to doublings. It depends on the piece and what color I get in my head for a given moment. There was a crazy one in an early piece called Turbine, where I put the melody in bottom octave piccolo sounding in unison with soprano sax, and that combo was doubled two octaves lower by a bassoon. It is a strange sound, but maybe it is because that combination is literally impossible to get in tune.

How can a conductor balance faithfulness to what a composer has written with coming up with their own interpretation of a work? What do you like to see? What bothers you?

One of my favorite conductors is Richard Clary at Florida State. With my earlier works especially, which were scored so thickly and with overwritten dynamics (Turbine starts with a full-ensemble quadruple forte, which honestly is just dumb), Clary has been a master at making every single line in a score jump off the page. He starts by telling the group to take every single dynamic in a piece of mine down by two levels and then as rehearsing, he brings out certain lines so that nothing is ever covered due to my scoring missteps. So, I look at the score, and I think I’m hearing what I wrote, but I’m hearing his interpretation of my dynamics. I’m hearing what I think I wrote. Things like that are exciting.

Obviously with slow emotive music, there’s a much wider range of what I find perfectly acceptable and interesting and beautiful. As the marked tempo goes down, in general I think the suitable amount of personal conductor interpretation goes up – dynamic shaping of phrases, pushing and pulling of tempo, and overall soloist expression. The faster the marked tempo, the pickier I tend to get about specific articulations and observation of the marked tempo. If I mark a tempo at 100 and it’s played at 82, that will make me insane. If I mark it 56 and “with rubato” and you do it between 48-60 given the place in the phrase, that seems fine. Junkin is a master of both of these extremes. Nobody does rubato like him, and with faster music, his tempos are impossibly consistent.

What do you find that ensembles performing your music tend to neglect?

It’s not that it is neglected, but the main thing I have to work on when I attend a rehearsal is the attention to the percussion section. Sometimes I wonder if some younger conductors study the score but only get down as far as the tubas. So, more often than not, I spend a rehearsal doing everything from asking percussionists to use the mallets that I explicitly requested, or choking cymbals faster than they had been, or tightening the hi-hat pedal, or – even in more cases than I’d like to say – pointing out to the marimba player that the marimba is not a transposing instrument, and the player is in the wrong octave!