.jpg) “Technically, the band is proficient, but too many intonation problems marred a good performance.”

“Technically, the band is proficient, but too many intonation problems marred a good performance.”

From my experiences with adjudicating bands across the country, I hear enough evidence that music educators are generally competent at teaching technique, but lack an organized approach to teaching how to play in tune. By incorporating intonation as a fundamental part of technique, students develop the habit of listening while playing.

Sing the music. Faulty intonation results when students don’t know how to listen. Singing requires listening, so have beginners sing every line before playing it. By progressing from scale-wise patterns to intervals, a format used in most beginning method books, young musicians learn to sightsing without realizing that it might be difficult. Try using singing as a regular part of rehearsals with junior high and high school groups as well. If students have never sung before, experiment by having each section hum its note when a chord is out of tune. Next, ask students to play the chord, then change to humming when you give the cutoff. If your students are listening, the chord should be in tune. You can transpose to a comfortable octave if necessary. Students are often inhibited the first time you ask them to sing. With a little practice, however, they can become more confident singers and will enjoy performing compositions that involve singing as well as playing. Including such a number on a concert not only improves singing and listening skills, but also provides variety for the audience.

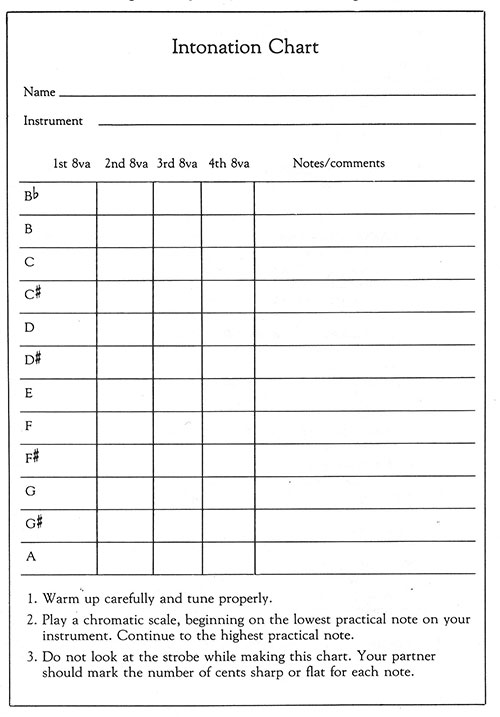

Develop an intonation chart. Using a tuner, work with each student to create an intonation chart that will make him aware of the general pitch tendencies of his instrument as well as his own inherent intonation problems. For example, flutes are generally flat in the low register and sharp in the third register, whereas clarinets are generally sharp in the throat tones and flat in the third register. After the student warms up, have him turn away from the tuner, then play a chromatic scale from the lowest practical note to the highest. Using the intonation chart, write down the pitch tendency of each note shown on the tuner’s display. Use a plus sign to show the number of cents sharp, +3, and a minus sign to indicate the cents flat, -2. A zero means the note is in tune. Have the student keep his chart in his music folder for reference. After he memorizes all tones over five cents sharp or flat, ask him to make a second chart with the goal of improving the readings from the first chart. When you evaluate the intonation chart, offer suggestions for alternate fingerings and slide compensations to improve intonation.

Listen to beats. A musician who listens can tell whether a pitch is sharp, flat, or in tune; students can learn this response by eliminating the acoustical phenomenon of beats, which result when notes are not in tune. Have two trumpet players sound an open tone with the tuning slide on one instrument pulled out as far as possible. Ask the class members to close their eyes and use their hands to represent the frequency of beats, moving them rapidly at first, then slowing them as the trumpeter pushes the tuning slide back in. When no beats are heard, all hands should be still. With this exercise you can observe each student’s aural perception.

I teach my high school students intonation by assigning unison scales; the goal is to play eight notes perfectly in tune. Scale ranges correspond to ability; a beginning trumpeter plays from C4 to C5; a more advanced student from G4 to G5; and the most advanced player from C5 to C6. Set the metronome at quarter =60, and ask the student to hold each scale tone for four counts, then let him identify which notes are out of tune. This assignment teaches students to concentrate on tuning as well as how to listen and adjust. It builds confidence in listening abilities, encourages the use of alternate fingerings and slide positions, and emphasizes good tone production. Consequently, I spend less time addressing intonation problems in rehearsal.

Using a tuner daily and telling students if they are sharp or flat doesn’t train them to listen. Instead, ask the ensemble members to tune to a sounding pitch and let them adjust themselves, offering help only if someone cannot make the correct adjustment. It is also a good idea to inspect each student’s instrument for needed repairs, such as warped pads on woodwinds and dents in critical segments of brass tubing, to alleviate potential intonation problems.

Exemplary intonation is no accident. If you approach intonation with the same resolve you apply to sightreading and building technique, your students will learn to play in tune.