Good intonation and balance are two basic elements that are essential to any good performance. When a band lacks either good intonation or balance, it is quickly and painfully apparent. Both conductors and ensemble members are responsible for good intonation and blend, but the process needed to reach these objectives is not always easily found. While intonation and balance are always a challenge, there are useful techniques that directors and band members can implement as they attempt to achieve their goals with these important elements.

Initial Tuning

Tuning is the essential first step of every rehearsal. Tradition dictates that orchestras tune to an A, because it serves the string section well. However, although the A works equally well for some wind instruments, it has only limited benefit for other winds. For this reason, many bands elect to tune to Bb or F as the principal note. Again, however, these notes serves some instruments better than others. To accommodate all of the various instruments of the ensemble most effectively, it may be best to use several tuning notes, instead of one, so that each instrument is given a tuning note that is best suited to it. Consider using specific tuning notes for particular sections of the band, as suggested below:

Concert F – horns, clarinets, bassoons

Concert A – strings, flutes, oboes, saxophones (all sizes)1

Concert Bb – trumpets, trombones, euphoniums, BBb tubas used in band playing

Concert C – C trumpets, CC tubas used in orchestral playing

The reason behind most of these suggestions should be readily apparent. The choices in many cases are based on the overall length of the instrument with few or no valves or keys depressed.

Most school bands will find that tuning to F, A, and Bb (C is seldom needed), as suggested above, helps to improve the intonation of the ensemble as a whole. This process usually works much better than just tuning everyone to either Concert F or Bb. Using these additional tuning notes does not take much longer, and the results are worth it.

One extra cautionary point about the tuning process is that students should be aware of the tendency to want to hear their pitch on the sharp side. Players may seek to find a comfort zone in which they are able to hear themselves, and more often than not, this tendency leads to a player’s pitch being high. To counter this tendency, especially with wind players, it is often a good idea to have everyone pull out so that all players begin the tuning process flat. It is usually easier for players to come up to the desired pitch, rather than come down to pitch. The director’s goal should be to bring everyone’s pitch to A440 and to try to keep it there so that this increasingly becomes the norm.

Another general rule to note is that when players are having trouble hearing themselves, they usually are closer to being in tune and blending with the rest of the section. Similarly, when two different instruments are playing perfectly in tune, they usually will blend their timbres, creating a new sound quality. Thus, when a flute and clarinet player are playing perfectly in tune with each other on a unison pitch, they will create a tone quality that is a hybrid of these instruments (a flutinet, if you will).

After the initial tuning is done, there should be an ongoing process of evaluating intonation, and this should continue throughout the rehearsal or performance. During this process pitch adjustments will be made through adjustments in embouchure or adjustments of the hands or finger, rather than from any changes to the length of an instrument. In making these adjustments the teacher and students will need to draw upon good listening skills.

Maintaining the initial pitch standard should also be an ongoing goal, especially when the performance is held on a well-lit stage that continually gets hotter as the concert progresses. Longer pieces may also cause the overall intonation to become progressively worse if individual players give in to the tendency to want to hear themselves, which usually makes the pitch go sharp. When this happens with a number of players, the overall pitch will continually climb as each player unconsciously gets caught up in a game of one-upmanship.

Modes of Tuning

Satisfactory intonation has been the subject of much study. Experimentation over hundreds of years has led to the development of a variety of tuning systems. Despite all of this study and experimentation, there is no tuning system that fits every situation, melodically or harmonically. Therefore, the goal with all tuning methods is to find a process that involves the least invasive compromises.

To appreciate the struggle to create functional ensemble intonation, it takes a basic understanding of Pythagorean, Just, and Equal temperaments, along with an understanding of how these three interact with each other.

Pythagorean Intonation: Tuning with Melodic Sense

Western tonality is based on scales of eight notes within an octave designed from varying patterns of whole and half steps. The placement of the half steps is the most critical aspect of each mode. For instance, a major scale (Ionian mode) can be divided into two identical groups of four notes. The first group of a C scale is C D E F, and the second is G A B C. Each group represents a perfect fourth, and each contains a leading tone, with half steps leading from E to F and B to C and with the intervals in each group being whole step, whole step, half step.

Pythagorean tuning raises the third and seventh scale degrees identically, placing them higher than Just and Equal temperament would. This raising of the third and seventh scale degrees creates what is known as tendency intervals, which allow for an enhanced melodic feel.

Just Intonation: Well-Tuned Intervals

Just intonation is the natural harmonic pattern based on sounds occurring from an open tube or a stretched string. For example, when a string is stopped at the mid-point of its length and then plucked, the resultant sound is double the vibrations per second or one octave higher. Just intonation requires an analysis of how intervals should be tuned, based on the interval relationships evident in the overtone series.

Just intonation is most helpful when analyzing intonation problems that occur with simple chord intervals, such as fifths and thirds. With perfect fifths, Just intonation would call for fifths that are naturally higher than in Equal temperament (which occurs when the pitches in a scale are divided as a series of evenly spaced half steps). Just intonation produces major thirds that are naturally lower and minor thirds that are slightly higher than those in Equal temperament.

After studying the intervals and tendencies in Just intonation, students will learn how best to tune these intervals. This understanding will help students to eliminate the sound of beats that occur when two or more notes in an interval are being played out of tune.

Equal Temperament: A Compromise

Equal temperament is a tuning system that is based on an octave divided by a series of half steps in which all of the half steps are equidistant from each other. Keyboard instruments, including piano and percussion keyboards, are all based on Equal temperament. Instruments with Equal temperament tuning do not use the natural sharpness of leading tones that occur when music is thought of melodically (as in Pythagorean tuning). Equal temperament also does not use the natural flatness of the third of a major triad, which occurs when pitches are thought of harmonically (as in Just intonation). Thus, except for octaves, Equal temperament is ultimately is a compromise, as it is different from both the Pythagorean and Just temperaments.

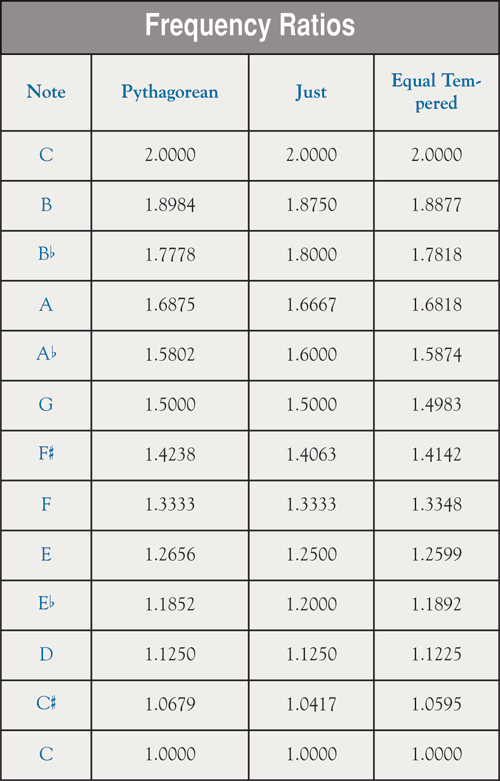

When comparing the various scale degrees in the frequency ratios listed below, pay close attention to the fifth scale degree (G), the third (E), and the seventh (B). Melodically, the third and fifth are noticeably higher in Pythagorean tuning when compared to Equal temperament, which reflects what the pitch tendencies of a melodic line should be. Also, the major third in Just temperament is noticeably lower than in Pythagorean and Equal temperament, which reflects how low the pitch should be in a triad that is correctly tuned. Notice also that the interval of a perfect fifth (C-G) and perfect fourth (C-G) are the same ratio in Pythagorean and Just temperaments.

The result is a blend between listening for what seems best both melodically and harmonically. All of this can seem overwhelming when trying to listen to everything with two different ears. The task of the conductor is to listen critically to all that transpires and to use the information above if any problem arises. Concerning the different temperaments and band intonation, Mark Hindsley once observed:

“It is my conclusion that we should try to have our bands play in a the combination of the just and Pythagorean temperaments. Theoretically and for practicality, wind instruments would be tuned to equal temperament in manufacture and adjustment: in their playing we should go as far as possible toward the tone pitches of the other temperaments. We should prefer the Pythagorean scale for melodic lines, but at the very worst may have to accept the equal scale, We should prefer the consonant, simple-ratio relationships of the just scale harmonically, but at the very worst we may have to accept the harmonic relationships again of the equal scale.”2

Which Method Is Best?

Research has analyzed which of these three modes of tuning performers most commonly use. In a study of how string players perform, the research showed that no particular method of tuning is adhered to at all times. However, it did show that when melodic patterns arise in tonal music, then the intervals tended to lean more toward Pythagorean tuning. Performers placed more importance on creating melodic leading tones, rather than on harmonic blend.3

The two other approaches, however, proved to be important at other times. When tuning simple chords, Just intonation is valuable. Equal temperament is acceptable when working on melodic lines and is preferable when tuning chromatic harmonies. In sum, however, no one temperament is completely acceptable in all cases, and all three approaches have their virtues at particular times and situations.

There also are times when inevitable compromises must be made. When playing with mallet percussion and piano, which are Equal temperament instruments that cannot make adjustments, the best choice may be Equal temperament. On the other hand, if the wind instruments are sustaining their notes, while the sound of mallet instruments or piano is decayed, then the sound of the winds may be the dominant sound to address when tuning.

Another occasion for compromise occurs when pitches are playing a dual role. For example, a pitch may be both the third of a chord and also the leading tone of the melody. It would be impossible to lower the pitch of the third to tune the chord, and yet also simultaneously raise the pitch of the note as a melodic leading tone. In these places, the ear has to be the guide. It may help to consider the length of the chord. If the chord is held for a long time, the tendency may be to place value on the chord intonation over the melodic tendency of the notes. Conversely, if the chord is short, the melodic tendency may be more important. Ultimately, you have to listen and decide which factor carries more weight at that moment in the music. It is also important to remember that a sustained note held through several chord changes may require an adjustment in pitch to fulfill the nature of the note within each chord.

Intonation and Balanced Dynamics

Achieving balance with dynamics can have a dramatic effect on the overall quality of the ensemble’s sound. This includes good balance between high and low pitched instruments, balance within chords, balance between octaves, as well as balance between musical components such as melody and countermelody. There are several concepts that may help in the ongoing challenge to play two or more pitches together with the proper balance and alignment.

Balance of Low and High Sounds

First, correct balance between low and high sounds is critical, not only for a good ensemble sound but also as an aid to better intonation. When played softly, high overtones are less audible. The upper instrument played at pp and the lower at mf will produce a more satisfactory result, both in intonation and in dynamics. Because there are fewer overtones audible in lower frequencies, it is generally perceived to be easier to tune to a low pitch rather than a high one.

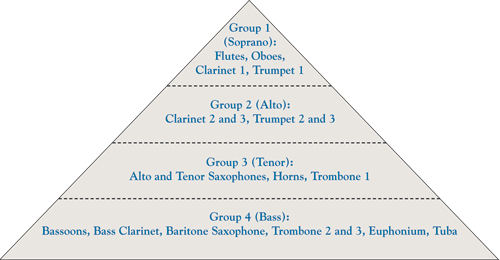

Francis McBeth advocates this approach in his book Effective Performance of Band Music. McBeth takes the position that the band has better balance and better perceived intonation if the lower instruments play successively louder than the high instruments. For example, the tuba should play louder than the piccolo and the third clarinet should play louder than the first. The balanced pyramid effect that McBeth proposes is shown in the diagram below.

When the ensemble plays in this manner, the lower overtones are not as easily dominated by the upper overtones, and a darker sound results. Whether the ensemble actually plays better in tune this way (as I think it does), or whether the ear just perceives that it is in tune (as some believe), the better results are obvious.4

An experience years ago gave me greater insight into this concept. I had arranged to have a concert recorded, and the person in charge of the recording process used new microphones that were attached to the floor at the front of the stage. The results were terrible. The recording reflected a great imbalance in the sound of the ensemble because the microphones picked up mostly just the first and second row players (i.e., flute, piccolo, oboe, and some clarinet). The sound of the ensemble with these instruments predominating was shrill, and it magnified every intonation inconsistency in the band, with very little of the rest of the group able to be heard. When I first heard the recording, I was bewildered as to how I could have allowed the ensemble to sound that awful, not realizing that the microphone placement had created a version of the McBeth pyramid in reverse. It was only when a student presented me a different recording of the same concert, made from the balcony situated well back from the stage, that I heard, much to my relief, a much more balanced ensemble, which sounded more like what I had anticipated for the performance.

Tuning Unisons and Octaves

The easiest interval to tune is the unison. Listen for the beats in the sound to check on intonation. The faster the beats are, the more out of tune the music is, and the slower the beats are, the better the intonation.

The octave is the next easiest to tune. A common problem often arises with octaves, however, which is the natural tendency of the upper note to dominate the lower. This tends to happen because the higher pitch has fewer low overtones in its sound. To counter this tendency and find balance, try to have the lower note played louder than the upper. In particular, have the upper note play at pp while the lower note plays at mf, and then notice the result.5

Overtones and Difficulty of Tuning

The number of overtones shared by two pitches in an interval will determine the difficulty level of tuning the notes together. The more overtones there are in common, the easier the tuning will be. For instance, when the overtone series for a C is compared with that of a G (perfect fifth), there are four pitches in common. Perfect fourths have three overtones in common, while major thirds, sixths, and seconds as well as minor thirds have two. Minor sixths and sevenths have one common overtone, and minor seconds, major sevenths, and tritones have none.6

When tuning a chord during rehearsal, a good method is to work from the easiest to the more difficult intervals to tune. With this approach, you would begin with the root and its octave. Then you would add the fifth (four common overtones), followed by the third of the chord (two common overtones). Once these notes are in tune, the seventh should be added if the chord has one. With the seventh, keep in mind the possible tendency of a major seventh to resolve up a half step and the tendency of a dominant seventh to gravitate or resolve down a half step.

Tuning Like Instruments

Versus Different Timbres

Many players find that it is easier to tune like instruments rather than tuning to another timbre. If the ensemble uses the approach of tuning to just one pitch, instead of multiple pitches (using the method discussed earlier), then it may be a good idea to tune the woodwinds and then the brass separately, or even tune by individual section. This way, students will be tuning to like timbres, which often makes tuning easier.

Discrepancy in Intonation

and the Length of the Tone

Whether intonation can be discerned is directly related to the duration of the sound. For example, if two instruments sound an A4, and one plays at 440 Hz and the other at 444 Hz, the difference of four cps (cycles per second) determines that if the tone is sustained for less than one-fourth of a second, no intonation difference is discernable. With a note an octave lower, if two notes are playing A3, one at 220 Hz and the other at 222 Hz, the difference of two cps would permit the tone to be sustained for almost one-half second without any evident difference in intonation. With a note an octave lower than that (A2), if one player is playing at 110 Hz and the other at 111 Hz, the difference of only one cps would dictate that the tone could be sounded for nearly one full second before the discrepancy becomes audible. Conversely, if the note is played an octave higher (A5), with one instrument at 880 Hz and the other at 888 Hz, a difference in pitch of eight cps will decrease the time at which intonation is detected to just one-eighth of a second.7

In these examples, even though the pitch ratio difference at each octave is the same, the time it takes for the pitch discrepancy to be discerned is much longer on the lower tones. That is because, with low notes, more time is required to establish the difference beat – i.e., the sound one hears when two notes aren’t quite in unison – and this is due to the difference in the wave-lengths. In practice, this means that a listener will notice two piccolos playing out of tune in a fraction of the time that it would take to hear two tubas or string basses playing out of tune.

Increasing Awareness

To develop good awareness of tuning and intonation, students have to be taught how to listen. This requires students to learn to be cognizant of their surroundings, and they also must learn about the particular acoustical properties of their instruments. Good intonation cannot be the conductor’s responsibility alone. Rather, correct intonation and balance should be the responsibility of both the players and the conductor. There is never a moment in the rehearsal or performance when either the players or the conductor will have the luxury of not listening critically.

Critical listening by the ensemble members is crucial. Here are some important concepts to emphasize when working with students on tuning and intonation.

You Can’t Tune a Bad Sound

Players should have a good concept of the characteristic sound of their instrument – a sound reflecting the quality of a professional player, absent any excessive pressure, pinched quality, or constriction. Most students use an inadequate amount of air, so they should focus on increasing both the amount of air and the speed of the air through the instrument. Playing with more air can solve many difficulties students have with tone, dynamics, and range.

The Effects of Temperature on Pitch

Students should have a good understanding of the effects of temperature on pitch. For winds the pitch rises as the temperature rises. String and percussion instruments react in the opposite manner.

The Pitch Tendencies of Each Instrument

Students should also know the pitch tendencies of their particular instrument – both the tendencies of the instrument in general, as well as the specific tendencies of their personal instrument. When students try to identify the tendencies of a particular instrument, it is good to have each student partner up with another student. As one plays, the other should record any discrepancy on each note as indicated by an electronic tuner. This method is better than having students work individually, because players working on their own may look at the tuner and adjust the pitch unconsciously.

Tuning to a Straight Tone, Without Vibrato

Students should get in the habit of always tuning to a straight tone, with no vibrato. Use of vibrato may cause some players to play the pitch higher or lower than normal. Tuning with a straight tone will keep any changing or masking of the tone to a minimum.

Keeping the Same Pitch at All Dynamics

Students should practice maintaining a consistent pitch while playing at all dynamic levels. A good way to work on this is to have students play crescendo and decrescendo exercises without allowing the pitch to go flat or sharp as the volume changes. Here are some instrument-specific suggestions that may help students as they work on this exercise:

• Flute. For crescendos, flutists should increase the opening of the aperture and gradually lower the direction of the air stream by pulling back the lips and lower jaw while increasing the air speed to keep the pitch from going sharp. For decrescendos, the flutist should decrease the opening of the aperture and gradually raise the direction of the air stream by moving the lips and lower jaw forward while decreasing the air speed to keep the pitch from going flat.

• Oboe. During a crescendo, the oboist should gradually relax the embouchure while increasing the air speed to keep the pitch from going sharp. On a decrescendo, the oboist should gradually firm up the embouchure while decreasing the air speed to keep the pitch from going flat.

• Bassoon. For crescendos, bassoonists should gradually relax the embouchure while increasing the air speed to keep the pitch from going sharp. On decrescendos, the bassoon player should gradually firm up the embouchure while decreasing the air speed to keep the pitch from going flat.8

• Clarinet. For crescendos, clarinetists should gradually increase the pressure of the lips around the mouthpiece, especially the lower lip against the reed, to keep the pitch from going flat as the sound gets louder. For decrescendos, as the sound gets softer, the clarinetist should gradually relax the embouchure and decrease the air speed to keep the pitch from going sharp.

• Saxophone. On a crescendo, a saxophone player should open the embouchure slightly and increase the lip pressure around the mouthpiece while increasing the air speed to keep the pitch from going flat. For a decrescendo, the saxophonist should maintain breath and embouchure support while decreasing the air speed to keep the pitch from going sharp.

• Brass. On a crescendo, brass players should gradually increase the aperture size to keep the pitch from going sharp. On decrescendos, brass players should gradually decrease the aperture size to keep the pitch from going flat.

Practice by Singing

Singing is also a good method of practice. If you can sing it, you will develop a better mental concept of how the music should sound when you play it.

Solving Intonation Problems in Rehearsal

There are times when problems arise with intonation, and there seems to be no clear way to begin the correction process. When this happens, there are a few ways to start work on solving the problem.

First, identify and separate the different melodic and harmonic components. With melodic lines, the concepts drawn from Pythagorean tuning may help. For instance, the third and seventh scale degrees typically should resolve toward the fourth and eighth scale degrees. With chords, try using the concepts of Just intonation. For example, when tuning a chord the fifth generally should be higher than Equal temperament, while the major third should be lower than Equal temperament.

A second good technique is to identify the different instruments that are playing the same line. Then, all of those instruments with the same note or line should work on listening and matching their pitch or phrase together.

Third, when working on tuning chords, focus on matching pitch in the following order: tune unison and octave first, fifths next, thirds after that, then sevenths, and so forth.

A fourth key to developing good ensemble intonation is to be sure that the ensemble’s balance is correct. This requires a good balance between high and low voices, good balance between notes in the chord, and good balance between different musical components (e.g. melody vs. accompaniment, melody vs. countermelody).

In preparing for performance the goal is always to eliminate anything that might distract from the music. To do this, a focus on the basic elements of good intonation and balance is essential. These elements will always be a challenge to musicians, regardless of their level of ability and experience. My hope is that the concepts and techniques discussed here, when put into practice by directors, will help students to achieve the goal of performing with great ensemble intonation and balance.

Endnotes

1 The Art of Saxophone Playing by Larry Teal, (Summy-Birchard, Inc., 1963), pp. 61-62.

2 “Intonation” by Mark H. Hindsley, Book of Proceedings, Sixteenth National Conference, College Band Directors National Association (1971), p. 109.

3 "Research in Pythagorean, Just Temperament, and Equal-Tempered Tunings in Performance” by Acton Ostling, Jr., Journal of Band Research, Spring 1974, p. 16.

4 Effective Performance of Band Music, by W. Francis McBeth (Southern Music Co., 1972) pp. 5-15.

5 “Methods for Improving Intonation,” by Wayne Bailey, The Instrumentalist, December, 1984, p. 50.

6 “Absolute Intonation and the Fusion of Wind Sounds” by William F. Swor, Journal of Band Research, Spring 1982, p. 24.

7 “Absolute Intonation and the Fusion of Wind Sounds” by William F. Swor, Journal of Band Research, Spring 1982, pp. 22-23.

8 Guide to Teaching Woodwinds, 5th ed. by Frederick W. Westphal (Wm. C. Brown Publishers, 1990) pp. 31, 75, 141, 184, 221.