When I was a grade school piano student, part of my instruction included a weekly theory/performance class. Sometimes our class attended the high school theory/performance class so that we could hear advanced students play their recital pieces. I am pretty sure this was intended to inspire us to practice harder or even practice at all. One thing I noticed right away in the high school class was that the pianists did not count out loud when playing their pieces while I had to count everything in a full voice. I remember thinking I can hardly wait to be older so I don’t have to count out loud. If my teacher had told me at the time that as I developed as a musician, I would actually count more parts of the beat in order to play accurately, I would have been surprised. I am thankful for her insistence in counting because having a good rhythmic understanding and execution makes for great sightreaders, and I love to sightread.

In band, woodwind and brass players cannot count out loud because they are blowing and articulating with the tongue. Many students incorrectly solve this issue by playing along by ear or rote which makes for sloppy performances. Of course, the solution is to teach students to count in their heads. However, counting in 12 in one’s head for extended lengths of time becomes quite unwieldy. For this reason, once students understand the rhythms and counting, it is best to simplify what they are saying internally. For example, in 12/8, I encourage counting four 1-2-3’s rather than 1-2-3-4-5-6-7-8-9-10-11-12. Some teachers incorporate syllables of words to aid counting in the head such as merrily, merrily for 6/8.

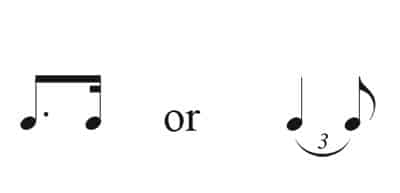

One of the most common mistakes students make is understanding where to place the second note in the following rhythms:

For an accurate performance, subdivision is the key. Ask students to subdivide by fours in the first rhythm (simple meter) and by threes (compound meter) in the second.

Time

Introduce students to the idea that there are three parts to time in music: tempo, meter and rhythm. The tempo is shown by a word or a few words at the beginning of the piece (or at beginning of sections later in the composition). Sometimes there is a metronome marking to pinpoint what the composer intended.

A word of caution: The metronome was invented by Maelzel in 1815. Wind-up metronomes varied widely in accuracy and were used until the mid-1980s when they were replaced with the quartz metronome. Metronome markings annotated before the quartz metronome should be noted with caution. Beethoven was the first to use the Maelzel metronome, but many later composers were not interested in putting metronome markings in their works. Often they were inserted by publishers. Composers Poulenc and Liebermann have both said that the metronome markings written in their works were incorrect. Richard Wagner’s friend, conductor Hans Von Bulow, remarked that there is one measure in every piece that indicates the tempo of the passage. This should agree with the metronome setting.

Meter is divided into two categories: simple and compound. Simple meter divides the beat in twos and compound meter by threes. In early music education, simple meter is taught first because the human body is in twos. We walk left, right. We open and close our eyes. We breathe in and out. Simple meter is easy to feel. Insufficient time is often spent on compound meter, and for most students playing in compound meter is a challenge.

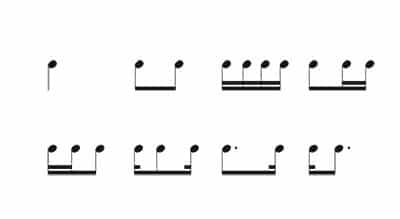

Rhythm is what happens on an individual beat. Just like in reading where 20 sight words are often memorized before moving onto phonics, there are eight rhythms in music that educators focus on in early instruction. These are:

There are several ways to teach these rhythms including using a pencil to tap on a music stand, clapping in the air or on the lap, and playing in unison on instruments. Practice playing in various tempos and varied dynamics. I like to do a passing game where one of these rhythms is passed from one section to the next, back and forth ping pong style, employing echo dynamics (woodwinds to brass and percussion or flutes to clarinets, etc.). Point out that a clean attack is a goal as is a clean release. Once students can execute these basic eight rhythms in simple meter, have them practice the rhythms piano style with the right hand tapping one rhythm and the left hand another rhythm. This aids in learning to play as an ensemble.

When I was in conservatory, we regularly practiced rhythmic reading. With the right hand, we conducted the number of beats in the time signature. With the left hand, we tapped the background (in simple meter this would be four sixteenths and in compound meter three eighths or six sixteenths.) And finally, we counted out loud which was eventually replaced with singing the pitches and dynamics.

This was showing the meter and rhythm in three different ways. One teacher said that the more body parts you can include in learning and understanding rhythm, the better. At the time I thought this was a challenge and had to practice rhythmic reading on a regular basis. However, in my performance career, this is how I have learned most of the new works in the repertoire that have challenging mixed meters or unusual rhythms and articulations. It was certainly worth the effort to learn this skill. How much of this you can teach to students depends on the level of advancement of the group and length of class time.

Subdivision

We skirt on teaching subdivision when teaching the difference between simple and compound meter, but as students advance, subdivision becomes more important. Students who study privately often are exposed to playing subdivisions in slow movements of Baroque, Classic and Romantic style sonatas and concertos, and orchestral students see subdivisions in slow movements of music from the Baroque on timewise. Sometimes this is called playing in eight because the eighth note is usually the consistent pulse throughout the repertoire.

Alla Breve and Subdivision

Most band students are exposed to alla breve or cut time in the first method book. Teachers can describe this to students by saying that it means to play what is written at double speed as if a flag or another flag is added to the stem of note. To subdivide the opposite occurs as a flag is removed. When going from a section in 4/4 into a cut-time section adding a “telephone pole” in the music prevents errors. Likewise, when going into a subdivided section, a “telephone pole” is also helpful.

Select some level 2 or 3 band music to use to begin teaching subdivision. Keep it simple with music written in whole notes, half notes, and quarters. The question asked is, “How many eighths are in a whole note – 8, in a half note – 4, and in a quarter note – 2.” This will seem tedious to some students so work in 4 or 8 bar units. Before playing, mark the telephone poles over the music. Eventually this will no longer be needed except in special instances. Discourage students from counting with their air stream as there is a natural tendency to do so when counting longer subdivisions. As you continue raising the difficulty level, you will encounter dotted notes. Playing dotted notes accurately is a good by-product of teaching subdivision.

Private teachers often use music books such as Rhythmical Articulation (A Complete Method) for singers and instrumentalists by Pasquale Bona, published by Schirmer and 48 Studies for Oboe or Saxophone, Op. 31 by W. F. Ferling, edited by Martin Schuring, published by Kalmus. I am particularly fond of the Ferling as the melodies are beautifully written and incorporate trills, gruppettos, and cadenza like passages. I also teach the slow movements of the Handel 12 Flute Sonatas before advancing into the orchestral repertoire.

Regular practice of alla breve and subdivided music leads to musical, accurate performances. As master teacher Nadia Boulanger said, “To live you have to count. One who counts best lives best. One should be a saint to be a true teacher. The eyes give food to the hands.”