Years ago, one of my students complained to the dean that she didn’t like the way I taught scales. The dean asked what was the problem. Her answer, “She makes us do all of them. In my high school band, we only did Bb and Eb.” Of course the Dean took my side, and I continued to teach all of the scales. I wondered though how many students go through a band program and never learn every scale.

Soon after, in a conversation with the symphonic band conductor, I mentioned my concern for the lack of knowledge of scales and in honor of the upcoming Olympics, I suggested we have a Scale Olympics with the flute section (16 flutists) challenging the other sections of the band to play all of the major scales in unison, two-octaves, with slurred sixteenth notes.

The competition was held during band rehearsal, and since the flutes had challenged the other sections, they went first. I was really proud of how they played all the major scales, slurred, two-octaves, in sixteenths with excellent ensemble. We had practiced in the weekly studio classes, but on this day, they played better than they ever had. The challenge was picked up section by section. The flutes were declared the winners and were awarded a pizza party. Several students remarked that everyone was a winner because they had learned their scales.

Later that spring, this band presented a concert at the state music educator’s conference. The concert was scheduled to follow a banquet. As we were finishing our desserts, the band entered and the conductor said they were going to warm-up for a few minutes. The band started in F major, playing the scale with two octaves, slurred, and in sixteenths. The diners continued to talk until they realized that the band was playing every major scale. After several keys went by, the ballroom became very quiet until they finished the 12-key cycle. Then the room exploded with a standing ovation. A band director at my table remarked that this was probably the only band in the state that could play all twelve major scales. Their efforts working on these scales resulted in a fantastic learning experience for the band. Tone quality and intonation improved throughout the year as had their technical skills. Pedagogically it was definitely worth the effort to learn more scales than merely Bb and Eb.

Teaching Scales by Tetrachords

Using tetrachords is a quick and almost painless way of teaching major scales. Students can learn the concept in less than an hour and then improve their tone quality, intonation, and tempo in the following weeks.

A tetrachord is a group of four notes with the first and the last being a perfect fourth. In the case of a major scale, the tetrachord is comprised of a whole-step, whole-step and half-step.

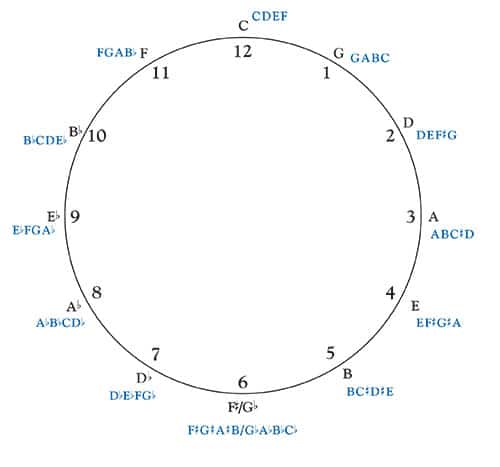

To introduce this concept, draw a circle of fifths on the board as indicated below and also include the numbers as if this circle were a clock. By each number write out the tetrachord in alphabet letters.

Have students practice playing the 12 tetrachords slurred one after another until each tetrachord is played quickly and on one blow of air. After a week or so, put two tetrachords together to play a major scale. So, to play a G major scale, students would play the G tetrachord – the 1 o’clock tetrachord – followed by the D tetrachord – 2 o’clock. These notes comprise the eight notes of the major scale.

Students will then continue the cycle by playing 2 o’clock plus 3 o’clock; 3 plus 4 o’clock etc. Proceed around the circle of fifths playing all twelve tetrachords. This simple drill teaches all 12 major scales in one octave in an understandable way. From here is it easy to add the second octave and the descent. As the year progresses, vary the articulation patterns and dynamics to keep this exercise challenging.

Choral Study

As a young band member, I always enjoyed playing chorales. I loved being engulfed in the richness or sonority of the sound. From one rehearsal to the next, I noticed how the band’s tone production improved as the instrumental sections learned to blend with each other. Our band director said that if one person was playing piccolo and another oboe, we should not hear the individual instruments but a blend of the two which he called picc-boe.

He had us play the contour of the hymn tune and showed that if one voice had a held note and another section had moving notes, then the held note should be played softer to let the moving notes sing through. Probably the biggest improvement though was in the area of intonation. Our director talked a lot about listening to the bass and setting the intonation from the lowest notes on up. Sometimes we played the hymn tune over the bass line omitting the alto and tenor lines to help us hear up the chord quality. At times we sang rather than playing our instruments. Looking back, it is evident how these pedagogical exercises contributed to the development of the ensemble.

There are many excellent chorale band books on the market. Some focus only on the works of J.S. Bach, who in his career harmonized over 400 chorales, while others are newly composed. One especially clever chorale book is Leonard B. Smith’s Treasury of Scales, published by Alfred. While the name of the book implies scale exercises, in essence it is a book of 96 chorales in four parts. The band instrumentation is grouped into four parts (soprano, alto, tenor and bass) with a scale (major or minor) written ascending and descending in one of the parts. All 12 major and 12 minor (melodic form) keys are presented. It is published with a conductor’s score with individual books for each instrument. An example from the book (Db Major) is shown below. Notice that the scale is in the soprano line.

From The Treasury of Scales for Band, Published by Alfred By Leonard B. Smith

While the chorale was a Baroque form, most bands do not follow Baroque performance practice when playing them. Usually, chorales are played in a Romantic-era glued style with molto rubato. Playing with rubato means students have to follow the conductor’s baton.

The three major areas of development from studying and playing chorales are sonority and blend, intonation, and rhythmic ensemble performance. The following are lesson plans to spur creative and engaging rehearsals. These ideas may also be used with woodwind quintets, brass ensembles and string chamber ensembles.

Sonority and Blend

Play the chorale through so each student understands what a chorale or hymn is. While no dynamics are indicated, use a mf level remembering to play the contour of the hymn tune. Play at various tempos such as quarter = 60, 72, 88. Once students are familiar with the chorale concept, then add rubato. Remember that Chopin said if a piece is two minutes long without rubato, it will still be two minutes long with rubato. Rubato means robbed and paid back. Then try the following:

Ask which instruments play a scale in the chorale and then have all students play that scale.

Play the chorale again but have students who have the scale in their music sing the scale.

Have everyone sing the chorale using la. If your program teaches solfege, then have students sing in solfeggio.

Have the soprano line play with bass line. Repeat with the alto playing with the bass line. Finally have the tenor play with the bass line. Since intonation is set from the lowest note, this helps students hear the bass line.

Repeat playing all parts.

If there is a moving part, ask who has that part. Remind students that moving parts should be a bit louder than held notes.

Have students play the chorale with their legs extended out in front of them. This exercise improves tone production because playing in this position shows how tight the abdomen should be when playing.

Intonation

Have students download a tuning app on their phones so they can practice intonation at home as well as at school. The first step in working on intonation is being able to play a note keeping the needle on the tuner still. This means the needle is still on the attack and duration of the note. At this stage, don’t worry if the note is sharp or flat, the goal is to simply figure out how to keep the needle still. An even air stream is the key. Practicing with the legs extended often helps at this stage. Once students can keep the needle still, you can pay attention to the pitch of the specific note. Often the attack is sharp and then settles to pitch. Have students practice breath attacks (HAH) to start the note. Then gradually add the T while still keeping the needle still. Remember the tongue releases the air stream.

Have students work in pairs to make a pitch tendency chart for each note on their instrument. With less experienced players, this exercise may need to be repeated depending on how much control a student has on the instrument.

Play each chord of the chorale one note at a time followed by a rest. Arpeggiate the chord (1, 3, 5, 3, 1) so that each student can mark in the part whether it is the 1st, 3rd, or 5th of the chord. For the major third, the third is lowered, and for the minor third, it is raised. To explore this idea, have the bass line play the note, then add the fifth and finally the third. Listen and explore to get the most resonance or ring.

Good intonation is fluid. For example, the clarinet section might finish a phrase playing sharp. Then the flutes take over the phrase in the lowest octave where they are often flat. The solution is for the clarinets to try to finish on the lower side of the pitch and for the flutes to try to enter on the sharp side of the pitch. It should never be approached as an “I am right and you are wrong” type of thing. A good ensemble is always compromising with intonation.

Rhythm and Ensemble Performance

The goal of every group is to play with good ensemble. This means that each student plays on the same part of the beat. Because most groups have players varying abilities, this means that the weakest instrumentalists generally play early on the beat, and the better ones play on the beat. Whoever plays first calls where intonation is, which may mean that the weakest players are setting intonation for your group. If the strongest instrumentalists set intonation, imagine how much better it could be.

The next exercise develops playing exactly on the beat by counting and playing the subdivision. Notice that the first part of the beat is always a rest. After playing the chorale with the indicated subdivisions, play it again straight through and notice how beautifully aligned the attacks are on the beat notes. A follow-up exercise is to play the chorale and fill in each beat with a background of eighths and sixteenths in simple meter and then again with eighths in compound meter.

Chorale Soprano Line

Play the chorale in quarter-note beats with each of the above subdivisions. Then create other subdivision patterns based on rhythmic passages in the literature the band is studying. This rehearsal technique may be applied to many passages in the literature, especially lyrical sections.

Leonard B. Smith writes in the preface to The Treasury of Scales, “Scale mastery is the basis and only lasting foundation for true musicianship. Since many of the student’s difficulties in sightreading, ear training and technical proficiency stem directly from his lack of familiarity with all of the scales, both major and minor, it follows that the principle is wrong which places demands upon the performer in excess of his ability.” One of my students commented that I not only teach scales but I practice scales. What a great observation.