There are a number of musicians in the world, particularly young ones, who think that they are rhythmically challenged. In addition, a certain percentage of musicians who think their rhythmic skills are satisfactory could benefit by improving this area considerably. To improve one’s rhythmic skills, a person must both believe that they can be improved and want to improve them. Once this is the case, students still need to know what to do. Below are my suggestions, based on 30 years of teaching lessons and 25 years of teaching sightsinging and ear-training classes.

Movement

For some, the skill of subdividing the beat would come first. However, even this skill would be improved by first ensuring that rhythm, meter, and motion have been fully linked in the mind. There are a wide variety of ways this can be accomplished, but they all typically involve some type of motion on the beat while singing and/or clapping the rhythm of a given song. Probably the best motion to do on the beat is to walk. So, for example, a routine for linking movement and rhythm might progress something like this:

01. Listen to a song in a simple meter (duple or quadruple), and determine where the beat is.

02. Take a step on each beat.

03. Sing or hum along with the song while walking.

04. Experiment with slower or faster beats: try walking twice as fast or twice as slow. Think about how these different rates compare to the first rate of walking.

05. With any but the fastest rate of walking, feel the off-beat by bobbing the head (or the entire body) twice as fast as the rate of walking.

06. Step a bit more firmly on the right foot than the left for a while, then try the reverse. For any given song and rate of walking, one should always feel more natural than the other.

07. Sing or hum the song again.

08. Try some different songs, gradually progressing towards some with more difficult rhythms containing dots, ties, or syncopation.

09. Try some songs in triple meter, noting how the strong foot alternates between left and right.

10. Try some songs in compound meter.

11. At some point, try clapping the rhythm of the song while singing, and still walking to the meter.

After exercises like these progress to a certain level of comfort, a good next step would be to read and clap various rhythms while walking. For many people, it is best to start with simple rhythms and increase the level of difficulty incrementally.

Next, it can be valuable to learn the various conducting patterns, at least for duple, triple, and quadruple meters. After achieving a certain level of comfort with these patterns, the student should sing various songs or rhythms while conducting. Conducting immediately provides a visual and spatial representation of how various rhythms fall with respect to the meter. Note that triple and quadruple meters can take some time to get used to, but duple should be able to work for them quickly. In addition, it may be best to start with songs in a moderato or andante tempo.

Once a student has progressed through a rhythm-and-motion regimen like this, they should keep it up for a long time, even if they only invest a few minutes each week in this type of activity.

Subdividing

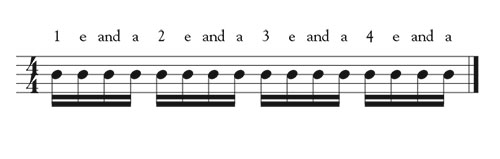

Once a rhythm and meter have been firmly linked to motion, efforts to improve subdividing should pay off. In my opinion, the most valuable way to practice subdividing is by counting rhythms aloud. Of the possible systems for doing this, I recommend the Eastman system for simple meters:

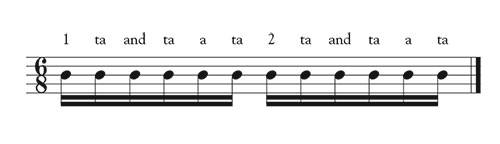

Unfortunately, I know of no system for counting subdivisions in compound meters that is nearly as user friendly to apply nor as widespread in its use. Below is the system that I currently use:

For best results, students should speak the written rhythms in a normal voice and whisper (or speak much more quietly) subdivisions that do not get articulated.

Some students might be tempted to skip this step, perhaps because they do not see the merits of it or do not want to work that hard. To make sure that your students are doing this, ask them periodically to submit a recording of an assigned excerpt. Another possibility is to take it upon yourself to convince them of the exercise’s merits, because there are no shortcuts to creating a stronger and more reliable rhythmic sense. One possible strategy is to use an argument by authority: challenge students to find a person whose rhythmic skills they respect but who is unable to do this exercise well.

Time Signatures

Some of the people who consider themselves rhythmically challenged are actually metrically challenged. Such people might know to hold a dotted quarter note three times as long as an eighth note, but that type of understanding is insufficient for rhythmic mastery, because the vast majority of rhythms that students will encounter will occur within a metrical framework, and it is this framework that some students need to understand and internalize better.

Common time is by far the best understood meter among beginning and intermediate musicians. For metrically challenged musicians, the goal is to become as comfortable in other meters as they currently are in common time. I would recommend that students tackle additional meters in the following order: 3/4, 6/8, quadruple and duple meters with values other than a quarter note in the denominator, triple and compound meters with different values in the denominator, then asymmetrical meters. I do not address 24 in the list above because I rarely see it pose a difficulty.

Students who find 3/4 challenging should very strongly accent every downbeat until the meter sounds entirely natural throughout the excerpt or piece. Similarly, the best remedy for those for whom 68 and other compound meters prove difficult is to accent every beat. To people for whom neither of these meter types are difficult, hearing so many strong accents can quickly sound plodding or belabored. Please be patient while struggling students get acclimated to these meters.

Meters with different denominators can be a stumbling block for young musicians until they get used to them. The main problem is a lack of experience reading these meters while endeavoring to understand them, so reading through a great deal of music in such meters is one of the best cures. Another useful strategy is to write out a particular rhythm first in a very common meter and then in one with a different denominator. It is also valuable to write well known simple songs, such as Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star, Jingle Bells, or Happy Birthday, in a variety of meters.

Ties and Dots

For some, the biggest rhythmic challenges are posed by notes of unusual duration or notes that do not begin on a beat. Usually, such notes involve ties or dots. The best strategy for quickly mastering passages containing dots or ties is first to remove them. Removing a tie is an easy enough concept. For example, you would play the following passage

like this instead:

The removal of a dot is essentially the same thing, because a dot is a type of tied note. So, the following passage with dots

is the same as the following rhythms with ties,

which would instead first be practiced like this:

Once a passage can be performed well without ties, it should not be very difficult to add them back in again.

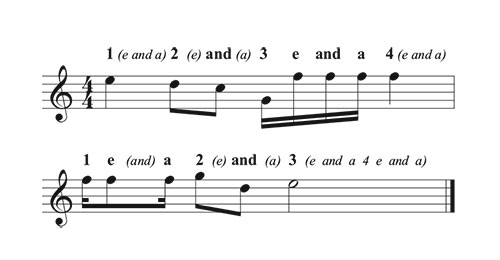

Another strategy is to leave in the dots and ties and also add accents where the beats occur. So, the first example above would instead be performed as shown at the top of the next column.

Note that the goal would never be to perform the passage with these additional accents. They are a temporary measure to help students get their brains around the rhythms.

Sightread Rhythms Daily

By and large, people learn by doing. Students who struggle with rhythm should get some sightsinging books and spend at least ten minutes a day, five days a week, reading rhythms. Ideally, students should have a metronome on for at least 60% of this time. However, tempo is not a priority; slow and accurate is better than fast and sloppy.

Transcribe Rhythms of Familiar Songs

After the above activities, a somewhat more advanced exercise is to transcribe rhythms. Rhythmic dictation always provides an excellent way to strengthen a musician’s rhythmic sense, regardless of how much time or how many hearings are required. It is a good idea to start with pieces that a student already knows, then progress to unknown pieces, starting with simple ones and gradually increasing rhythmic complexity. Only as the final step should the number of hearings or the amount of time to complete the dictation be decreased.

Conclusion

By following the recommendations above, good rhythmic skills will eventually come. Some students will wish for a short cut, but, in my experience, the regimen outlined above is the shortest route to success. Above all, students must be persistent and patient with themselves. l

Suggested Reading

Rhythm

Basics in Rhythm by Garwood Whaley (Delray Beach, Florida: Meredith Music, 2003).

The Rhythm Bible by Dan Fox (Van Nuys, California: Alfred, 2002).

The Rhythm Book: Studies in Rhythmic Reading and Principles by Peter Hampton Phillips (Mineola, New York: Dover, 1995).

Rhythmic Training by Robert Starer (Chicago: MCA Music, 1969).

Sight Reading: The Rhythm Book by Alex Pertout (Fenton, Missouri: Mel Bay, 2010).

Studying Rhythm by Anne Carothers Hall (New York: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2005).

Sightsinging

Anthology for Sight Singing by Gary Steven Karpinski and Richard Kram (New York: Norton, 2007).

Manual for Ear Training and Sight Singing by Gary Steven Karpinski (New York: Norton, 2007).

Melodia: A Course in Sight-Singing by Samuel W. Lewis (New York: Carl Fischer).

Movable Tonic: A Sequenced Sight-singing Method by Alan Clark McClung (Chicago: GIA Publications, 2008).

Music for Sight Singing by Thomas Benjamin, Michael M. Horvit, and Robert Nelson (Wadsworth Publishing Company, 2012).

Music for Sight Singing by Robert W. Ottoman and Nancy Rogers (New York: Pearson Prentice-Hall, 2013).

A New Approach to Sight Singing by Sol Berkowitz, Gabriel Fontrier, and Leo Kraft (New York: Norton, 2013).

Progressive Sight Singing by Carol J. Krueger (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).

Sight Singing by Earl Henry (New York: Prentice Hall, 1997).

Sight Singing Complete by Maureen Carr (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2014).

Sightsinging Complete by Bruce Benward and Maureen A. Carr (Wm. C. Brown, 1991).

Available at the International Music Score Library Project

1000 Exercises by Arthur Somervell (London: J. Curwen & Sons Ltd, 1911).

Graded Studies in the Art of Reading Music at Sight by Horatio Richmond Palmer (Cincinnati: The John Church Company, 1891).

Melodia: A Comprehensive Course in Sight-singing by Samuel W. Cole and Leo Rich Lewis (Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania: T. Presser, 1909).

The School of Sight Singing by Giuseppe Concone (New York: G. Schirmer).

Sight Reading Exercises, Op. 45 by Arnoldo Sartorio (London: Augener, 1909).

Solfège des solfèges by Adolphe Danhauser (New York: G. Schirmer, 1891).