Rhythm is one of the most frequently missed elements during sightreading, so finding a way to improve understanding is paramount. There are numerous methods for teaching rhythm, but finding a method that teaches students how to count rhythms independently and can be quickly incorporated into warmups has been more difficult. In 2005 I worked with Chicago-area middle school students to measure the effectiveness a visual system had in aiding rhythm reading and improving sightreading. The effectiveness of this system, known as the Dot System, showed heightened results when used versus other students who did not employ this method.

Understanding the Dot System

The Dot System uses the smallest subdivision necessary for most rhythmic patterns – the sixteenth note. The system pairs with any rhythm-syllable method and provides students the opportunity to analyze rhythm patterns independently by assigning dots to each note in a given rhythm. After assigning the dots, students can then transfer the correct syllables that relate to the pattern. The system also helps students by displaying each note’s duration compared to other notes. While the understanding of proportions through the assigning of dots is not completely necessary, having this information may assist the students who best understand abstract concepts through visual aids.

Using the System in Rehearsal

To begin, I always ask students, “How many sixteenth notes does this note receive?” From their answer I will then assign the appropriate number of dots (sixteenth notes) to each note. Sixteenth notes get one dot, eighth notes get two, quarter notes four, half notes eight and whole notes 16.

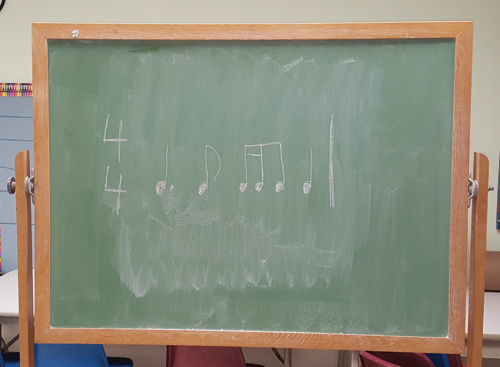

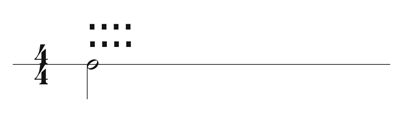

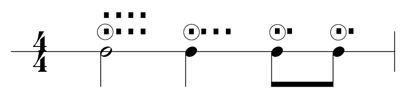

After students answer, I will then assign the correct number of dots above the rhythmic figure. To assist students with accounting for the correct number of sixteenth notes, I will often limit the number of dots each note receives to four per line (which may assist with further defining the quarter note pulse). For example, a half-note would receive eight dots, representing eight sixteenth notes. If notated without a break, it might clutter the remaining rhythm analysis and make it difficult for students to know whether they counted the note value accurately. Instead, limiting the number of dots to four makes it more readable and allows for the student to confirm accuracy:

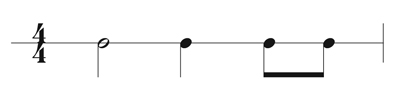

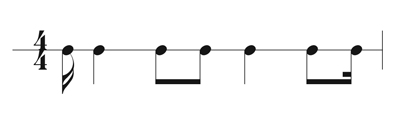

The following example shows how to employ the Dot System in everyday warmup and rehearsal.

The first step is to ask the students, “How many sixteenth notes does each note receive?” After each note, the director would notate the rhythm as:

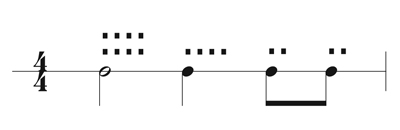

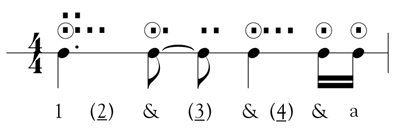

To check answers, use simple multiplication of the two numbers in the time signature to confirm the correct number of dots in each measure. Four times four is sixteen (students should be the ones to answer this), so in 4/4 time, there should be 16 dots, one for each sixteenth note. A 3/4 measure will have 12 dots. Confirming the number of sixteenth notes using this method works only with time signatures where the quarter note is the pulse. It is recommended that the director use rhythms in these time signatures first before exploring time signatures in which the pulse is something other than the quarter note.

A student who has difficulty understanding rhythm as an abstract concept may find the visualization that the first note (the half note) receives twice as many dots as the next note (the quarter note) and the last two notes receive half as many dots as the quarter note.

Once dots are assigned, the director should circle the first dot in each set.

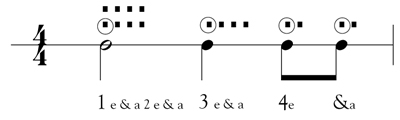

From this the ensemble can move to the counting system they already use. Circling the first dot in each set shows which syllables to articulate. The example below shows every syllable with the omitted syllables for analysis faded and in smaller font.

This can be a helpful transitional step for students to see if needed, but I usually just write the syllables that are to be articulated on the board.

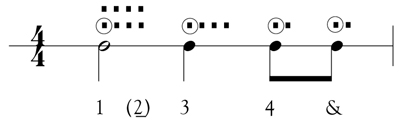

It is ideal for students to know where in the rhythm the pulse occurs. If a pulse is part of a held note, I include it in parentheses and underlined, indicating that it is not to be rearticulated. If there are rests in a measure, I notate them in parentheses but without the value underlined.

Having the analysis and visualization of rhythmic proportions represented by the dots might assist students in becoming stronger rhythm readers. The ability to write down the rhythmic analysis will not increase proficiency at performing a rhythm, but it does give students a second tool to add to a familiar counting syllable system.

Application

There are several practical uses for the Dot System in rehearsal. As students enter the rehearsal hall have them take out a notebook, copy a rhythm from the board, and analyze it. I start the year with simple rhythms and work toward more difficult ones as the year progresses. The rhythm presented can be from the literature being rehearsed or one constructed by the director. Before taking the podium, I ask for a student volunteer to announce the analysis both above (dots) and below (syllables) the given rhythm. If correct, I then have the ensemble perform a scale with the rhythm of the day played in its entirety on each pitch ascending and descending.

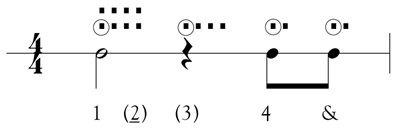

On the day of a football game, I often limited playing time during the school day so students’ chops were functional that evening. One activity we did those days was to play stump the band director. Students selected a classmate to construct a rhythm. My responsibility was not only to analyze the given rhythm, but also to perform the rhythm in a key of the student’s choosing on my trombone. The only rule that I implemented was that the rhythm I was given had to fit the time signature correctly. Students would receive a prize if I was unable to analyze the rhythm accurately within 30 seconds, I could not perform the rhythm correctly after have one minute to practice, or the student who provided the rhythm could accurately perform it in a key of my choosing. While the prizes ranged from receiving a small trinket to being able to select a stand tune to conduct later that evening at the game, the joy for most of the students was to stump the band director. Needless to say some of the rhythms became very demanding and quite creative:

As the ensemble director, it was encouraging that my students were able to develop their skills to analyze rhythms of this magnitude. In all honesty, it challenged me as their director and as a musician to perform such rhythms.

Ties and Dotted Rhythms

Ties and dotted rhythms are treated the same as notes that are longer than a quarter note. In the following rhythm, the analysis would be given as:

Of particular interest is the dotted quarter note in the above example. Similar to the rationale of splitting the dots of note values greater than a quarter note, accounting for a dotted rhythm by having the dots above the primary note helps students realize that they have accounted for the note and its dot. The same can be done with a dotted eighth note:

Triple Meter

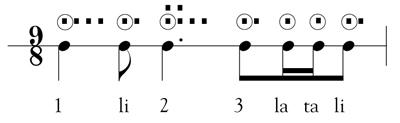

Rhythms in triple meter can be analyzed similarly to those in duple meter. What might be different is the director’s choice of syllables. The following rhythm in 9/8 time shows one possibility when using the syllables 1 ta la ta li ta. (six sixteenth notes per dotted-quarter note pulse):

The ability to read, understand, and perform rhythm is extremely important. As students begin to grasp the concept of using the Dot System, they will be capable of analyzing more difficult rhythms. Although this acquired skill will be helpful, the ability to play more difficult rhythms only becomes obtainable with practice.