As part of our 70th anniversary celebration, we will be revisiting a few classics from our archives. This article first ran in the November 1986 issue.

Nothing is as essential to a jazz performance – whether by a combo, a vocalist, or a big band – as the ability to play “in the groove.” This steady sense of pulse eludes many ensembles. In fact, as a jazz festival adjudicator, the question I most often hear among my colleagues is “where’s the groove?”

Maintaining a good jazz groove calls, first of all, for attention to the beat or pulse. Different tempos and styles can alter the sense of what’s happening to the pulse. Paying attention to these changes is what produces a good groove.

For students, developing a focused approach to listening is the first step toward understanding how to play in the groove. Because a jazz chart provides only a rough blueprint for the player, an appreciation of the techniques and subtleties that characterize the rhythmic essence of jazz can be gained only through careful, systematic listening.

Recordings of Count Basie’s rhythm section provide a solid example of a group that stayed together, kept steady time, and generally contributed to the body of music known as jazz. Dozens of Basie’s big-band and combo recordings are available today. You could pick up practically any one of them and gain insight. You may want to select one album to demonstrate the big-band setting and another to show the combo; for the most part, though, you will observe the same phenomenon regardless of the ensemble. If you’re eager to select a single album, I would recommend the exceptional Warm Breeze recording.

The first time you listen with your students, you should focus almost exclusively on the rhythm section. First, point out that Basie’s rhythm section never gets in the way of the rest of the group. Often their performance is so understated and simplified that you have to listen intently to know they are playing; yet all the while they provide a consistent, solid foundation that puts the band at ease. The rhythm section truly illustrates the principle that less is more.

As you listen to Basie’s rhythm section play at different tempos in various performances, you should notice that the players’ reactions depend on the specific conditions. When Basie plays a slow tempo, the rhythm section seems to delay the beat ever so slightly. This laid-back, behind-the-beat style should not be confused with dragging the tempo. The tempo remains constant, but the beat seems to be pulled between the band and the rhythm section, each playing on slightly different parts of the beat (the band more on the beat, and the rhythm section slightly behind). This helps create a sense of tension for a tempo that otherwise would seem listless and perhaps even uninteresting.

When young bands perform Basie’s charts or other pieces at a slow, relaxed tempo, they often fail to match the light, unhurried sound of the Count’s band. Achieving the subtle dualism of the beat characteristic of Basie’s group is undoubtedly demanding; but the alternative is to give a slow, boring performance that loses the audience. Some groups that try to replicate the delayed feeling of Basie’s rhythm section only end up playing progressively slower throughout the piece. This unmusical approach results in the band sounding (and indeed often feeling) tired.

At a moderate tempo (q = 120-180) the Basie rhythm section aligns itself more with the beat, along with the rest of the ensemble. Here again, there is always a strong sense of the rhythm section performing as a unit to obtain a solid groove. Most of this sense of solidarity results from each member of the rhythm section being concerned with complementing what the other members of the section are playing. The rest is achieved through a sensitivity to the metric sense and overall mood of the music. Although Basie’s rhythm section may move the feel of where the beat is, according to the tempo, concern for playing as a unit and an ever-present sensitivity to time is what ultimately characterizes Basie’s playing as being in the groove.

In up-tempo pieces, Basie’s rhythm section functions in a manner almost opposite from the way it approaches a slower tempo. At the faster tempo the pulse appears to be slightly ahead of the actual beat, giving the music drive and intensity, yet the actual tempo is always solid and I never feels rushed. In brighter tempos they play lightly, never hammering away at the beat. Even at blistering tempos, the rhythm section never I intrudes, exhibiting a sense of restraint. When the drummer, pianist, bassist, or guitarist is even momentarily prominent, it is to complement and spotlight the other players. Overall, the rhythm I section is responsible for maintaining control and reserve, providing the wind players a secure foundation from which they can perform at their peak. Basie’s soloists also carry on a solid sense of pulse that is especially prominent in the solo break, a favorite device of Basie’s. During this event the entire band, including the rhythm section, stops while the soloist plays two, four, or more measures alone. When such a break occurs, the sense of time is always particularly strong, and the soloist sustains this sense so that when the rhythm section (or the entire band) comes back in, it does so solidly, helping to produce a strong sensation of rhythm in the listener.

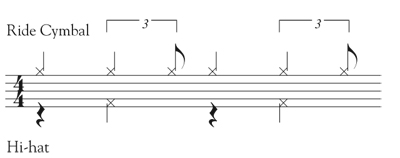

Now that your students have heard how crucial the rhythm section is to obtaining a solid groove, you can begin teaching traditional techniques and precepts of jazz comping. Rhythmically speaking, everything begins with the drummer. To help your drummer develop a good swing groove, have him begin by keeping time with the hi-hat cymbal only on the second and fourth beats of the measure. Each time the cymbal closes there should be a clear, distinctive “chick” sound. Once the player can maintain this pattern he should add the ride cymbal in a typical swing pattern that, when combined with the hi-hat, would look like this:

Only after your drummer can play this pattern securely should he gradually add the entire drumset, using the left hand and bass pedal. This is usually the time that young drummers create problems that interfere with setting a groove. Encourage the player to restrain the left hand, making sure that it doesn’t interfere with the swing feel. In addition, the bass pedal should be kept light, providing a delicate sense of pulse.

The bass player may well have the most critical role of any single member of the group. He has the responsibility for providing the harmonic foundation while scrupulously maintaining a sense of time. The difficulty of the role is compounded by the need for the bassist to play with taste and mature musicianship. It’s little wonder that many young bands have problems keeping a groove when a single player is so vital to the ensemble.

To help your bassist achieve a solid groove technique, have him first concentrate on keeping time with a legato sound. He should strive for a relaxed approach, using a fluid articulation and avoiding a ragged quality. Even a young player can learn to observe the difference between major and minor qualities in chords. This is a big problem for young, inexperienced bassists, and it can really work against the effectiveness of an ensemble. Bass lines should, as a rule, use the root or fifth of the chord on the first and third beats of the measure. The second and fourth beats may use passing tones, but repeated tones should be avoided.

At the same time the bassist should be sensitive to the pulse of the music. An inexperienced bass player should work hard to maintain a metronomically even beat. Once that is secure, have him begin to emphasize the second and fourth beats when playing swing figures. Once he can provide a walking bass that maintains strict rhythm, using the proper notes within the harmonic structure and making the appropriate changes, he has mastered the basics. Now encourage him to add chromatic tones a half-step above or below a new chord change on the fourth beat of the preceding measure, using the new chord to help accent the progression.

I’d like to add an admittedly biased view about jazz basses. In some circumstances the use of the electric bass guitar is appropriate and even desirable. In school jazz programs, though, this instrument has been used in situations beyond these acceptable settings. The rationale for this, of course, is always that student interest does not go beyond learning the electric bass guitar. This is no justification for failing to encourage students to master the acoustic bass as well. The process is no more dramatic or demanding than the common transition from clarinet to saxophone.

Today’s professional acoustic jazz bassists perform music that would have been considered impossible for the instrument just a few years ago. A student bass player needs to have as comprehensive an understanding of all facets of bass playing as possible. In addition, jazz performance requires the appropriate use of the right instrument under the right circumstances to satisfy the aesthetic demands of the music. Certainly in the case of traditional swinging jazz the acoustic bass contributes significantly to the overall groove feel. Everyone in the group will benefit if you can convince your bass students how important it is to master the acoustic bass.

Once you are satisfied that the drummer and the bassist can work together as a unit that maintains a solid beat, you are ready to bring your pianist into the picture. Student pianists often are confused when they first perform jazz. This usually stems from a general lack of formal preparation and a disparity between the music they have studied and what is expected of them in the jazz ensemble. Having the pianist proceed slowly in a system that gradually builds technique in a logical sequence of levels will enable the player to develop skill and confidence and allow him to perform with the ensemble at all stages of progress.

The first step of jazz comping is to develop facility at playing simple two-measure rhythmic patterns in octaves. Unquestionably, the key word here is “simple,” and you should make certain from the outset that your pianist avoids playing too busily. The pianist should strive to leave open spaces in the voicing in the same manner as Count Basie. This way, piano lines will not interfere with the melodic lines played by the soloist.

The following rhythm patterns are recommended to help guide your pianist through the initial stages. Remember, at the beginning the pianist should only use octaves with these patterns.

Piano Comping Rhythms

After your pianist is able to use these rhythm patterns naturally and creatively within the context of the music, have him harmonize them in block-chord voicings. The following sequence represents one possible approach.

• Start with root position chords, playing only these until progressions are smooth and comfortable.

• Progress to inversions.

• Begin using common-tone chord progressions. The pianist should be concerned about repeating common tones between chords in the progression. Be sure that chord changes fall on the first beat of the measure whenever appropriate.•

• Now begin using open voicings in the left hand (with fifths, fourths, sevenths, or octaves) and closed voicings in the right hand (seconds, ninths, thirds, and so on). Avoid playing roots.

Other approaches to piano voicing are available, most notably Jimmy Amadie’s Harmonic Foundation for Jazz & Popular Music.

In traditional jazz settings, the guitar is optional. Of course, if your group performs many jazz-rock or funk tunes, the guitar becomes more important. No matter what the style considerations, it is vital that the guitar not interfere with the piano. The entire rhythm section should always listen carefully to ensure that this never happens. If you do use a guitar, make sure that the rest of the rhythm section is already performing in a tight groove before making these suggestions to the guitarist.

First, have the guitarist set the amplifier volume level on low so that it resembles an acoustic guitar. (This may be the most difficult task you encounter.) The guitarist should avoid using barré chords (which use open strings and an all-six-string strum). Two-note voicings are particularly effective when they make use of the third, sixth, or seventh in the chord. Finally, in swing charts, your guitarist should comp on all four beats, playing quarter notes with light accents on the second and fourth beats (thus providing an extra emphasis to what the bass and hi-hat are performing).

If you can persuade everyone in your rhythm section to listen to models of individuals and rhythm sections to better understand his own function within the ensemble, you will have taken a big step towards helping your group play in a jazz groove. Furthermore, if you can get your rhythm section to concentrate on the basics outlined here, you will find that achieving a groove performance is that much easier.

Every member of your ensemble should listen to each other so the group plays together as a unit. The first step is for each player to assume that he is wrong and adjust to the rest of the group. Each player should compromise rhythmically and melodically to conform with the others in the ensemble. This means, of course, that members recognize and agree upon the musical objective for each piece. Impress upon them that they need to continue to listen and adjust throughout the performance.

Adjusting to others calls for good communication, whether through eye contact or body movement. The following example demonstrates how this process evolves from the first reading to a performance before an audience.

Assume that you have selected a new swing chart for your jazz group. First, the group should read through the chart and work mainly on perfecting the technical details, simultaneously listening carefully to gain an overall feel for the composition. When your ensemble can accurately play all the rhythm patterns, accidentals, and key changes, along with the indicated articulations and dynamics, you can progress to the next challenge.

Identify the elements of the performance that contribute most significantly toward providing a jazz feel. These might include a shout chorus, a tempo change, a saxophone or trumpet feature, or a specific mood change. Anything that gives the music a distinctive character should help you in your decision, and your main objective should be to exploit this special character.

This is the logical time to bring a recording to your rehearsal to demonstrate your rhythmic objectives. Rather than having your group mimic a famous recording of the work you are rehearsing, have them listen to a recording of another composition that demonstrates the same feeling of a groove. This way, students can learn general concepts and apply them to the chart you are rehearsing.

During the same period, the rhythm section should play at a low volume level. When this doesn’t happen, the result is rhythm players who don’t play logically or with any comprehension of the piece. If the rhythm section doesn’t take the time to listen to how the piece is constructed and how they should consequently interact, their playing may be inappropriate to the piece, neither complementing the band nor supporting the groove. When that happens, it is difficult to obtain a good groove feel within the ensemble. Only after the rhythm section fully understands how the piece is constructed with respect to form, contour, and general feel, can they begin to expand their parts. At any time, a rhythm player should be able to justify what he is playing based upon the construction of the chart.

The next step in the procedure is probably the most dramatic for many conductors because it departs so drastically from traditional conducting strategies. You should now experiment with the various elements of the piece so that you highlight your ensemble’s strengths. This may mean changing the form, adding or subtracting a chorus, altering dynamic levels, or taking a different tempo. Each ensemble has its own personality; any director who inflexibly forces a group to play a chart as written when the group naturally expresses the work differently is working outside the jazz tradition and creating unnecessary problems for the group. What’s more, the piece probably will never work well in performance. Part of setting a groove involves an emotional, expressive element. Balancing emotion with technique is a matter of taste, but both must go into the performance. It is this balance that makes jazz distinctive and appealing to contemporary audiences.

Once the technical problems have been solved and the director has adjusted the chart to suit his players, the rhythm players should open up their performance. Always concentrating on the groove, these players should have more freedom in their role as the section most responsible for the groove. As the core of the jazz ensemble, the rhythm section will dictate the overall impact that the ensemble makes.

There is no guarantee that an ensemble will win additional trophies at jazz festivals if you follow these procedures, but they will receive more compliments from audiences and develop higher self-esteem about their playing. Playing in the groove cannot magically solve all problems, but it is fundamental to creating an authentic performance. By following Count Basie’s example, your students can learn to listen and play together as a unit that shows taste and style and – most important – that stays in the groove.

Author’s note: The following are useful jazz references:

Jazz Lexicon: An A-Z Dictionary of Jazz Terms in the Vivid Idiom of America’s Most Successful Non-Conformist Minority by Robert S. Gold (New York: Knopf, 1964).

Jazz Styles by Mark C. Gridley (Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, second edition, 1985).

Harmonic Foundation for Jazz & Popular Music by Jimmy Amadie (Bala Cynwyd, Pennsylvania: Thorton Publications, 1979).