Currently there is only one standard work for a flute and cello duo, the 20th-century gem Assobio a Játo (The Jet Whistle) that was written by Heitor Villa-Lobos in 1950. There are a handful of other flute/cello pieces, including Elliott Carter’s Enchanted Preludes, Barbara Kolb’s Extremes, and Hilary Tann’s Llef, but none approach the effectiveness and charm of The Jet Whistle. The piece is dedicated to Elizabeth and Carleton Sprague Smith. Carlton Sprague Smith, an avid flutist, was a musicologist, music librarian, and chief of the New York Public Library’s music division from 1931 to 1959. He also taught music and history at New York University from 1939 to 1967.

Currently there is only one standard work for a flute and cello duo, the 20th-century gem Assobio a Játo (The Jet Whistle) that was written by Heitor Villa-Lobos in 1950. There are a handful of other flute/cello pieces, including Elliott Carter’s Enchanted Preludes, Barbara Kolb’s Extremes, and Hilary Tann’s Llef, but none approach the effectiveness and charm of The Jet Whistle. The piece is dedicated to Elizabeth and Carleton Sprague Smith. Carlton Sprague Smith, an avid flutist, was a musicologist, music librarian, and chief of the New York Public Library’s music division from 1931 to 1959. He also taught music and history at New York University from 1939 to 1967.

This three-movement duet is technically challenging for both players and calls for an extra dose of stamina from the flutist in the last movement. Each musician must find solutions to the musical challenges. Consider the following suggestions as you explore.

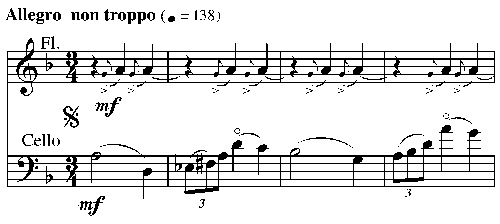

Allegro non troppo (quarter note=138)

The cellist begins the lyrical D-minor, 16-bar melody that ends on the dominant. This melody repeats and then takes a different direction in the eighth bar by descending chromatically to land on the tonic. The flute serves as accompaniment and percussion here, spurring the cello on its long melodic way. Make sure the G grace notes receive the accent. I believe the slur marks that extend from beat three into the next measure are the decay of each “drum beat.” Tune the As to the cello melody, and despite the mf dynamic, avoid dominating the cello.

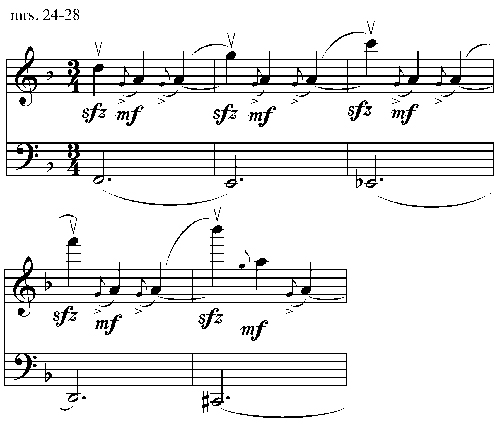

The V marks over the sfz downbeats in bars 24-28 are unusual. Perhaps Villa-Lobos actually wanted a feeling of an up bow on the downbeat, but I believe it suggests short, accented notes. Holding the top high B flat in measure 28 a little longer will reinforce the climax.

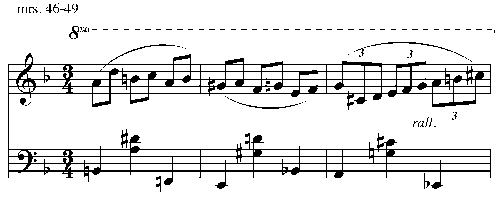

When the flute takes over the melody in measure 33, there are no clear, logical breathing places because the long 16-bar phrase dovetails into the next long phrase. Each flutist must find places to breathe that feel the least problematic. Most players breathe after bar 36, after the D at the a tempo in bar 49, and on the barline four measures before the da Capo. Otherwise, I take catch breaths on the barlines, although many prefer to breathe after the first note in any measure between bars 41-47.

While the first movement is written in 3/4, players should feel the music in two-bar groups, as if the music is in 6/4. This is a challenge for cellists because the numerous double stops on the second beat of the measure can easily be too loud and destroy the larger pulse. The music dove-tails, spinning like a leaf that is swept up, drifts down and is swept up again and again in the wind. This is one of Villa-Lobos’ many Bach-like characteristics.

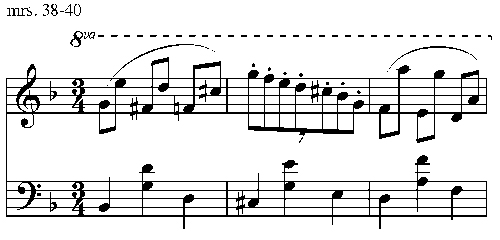

Practice the septuplet figure in measure 39 three ways: 2+2+3, 2+3+2, and 3+2+2. Then feel the music propelled from the last two eighths of measure 38 into the first note of the septuplet, which should fall down into the F in measure 40.

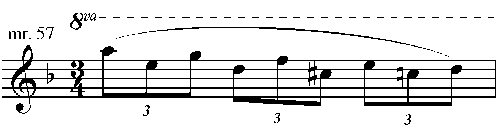

Be aware of focus-notes or climax notes. The G# in measure 47, for example, is an effective target. Drive the intensity into it, relax the note a bit into the next measure, sweep up through the rallentando, and ease back into tempo for the next 16-bar phrase. The next target note could be the high A on the downbeat of measure 57.

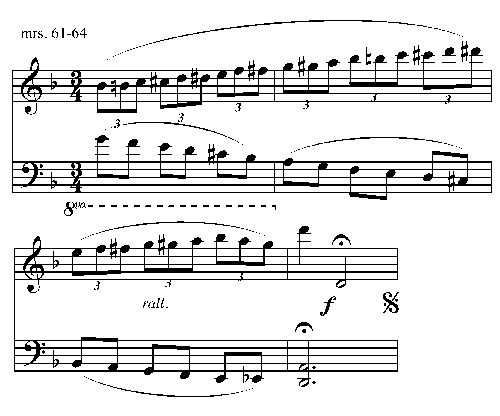

Listen carefully to the intonation because the cello also has an A. Make sure these octaves are in tune. Let the music unwind until the dramatic section ends. The cellist can linger on the last beat of measure 60 to give the flutist time to breathe.

To practice the ensemble in the last four measures, I suggest that both players try counting their notes out loud. Flute 1, 2, 3, 1, 2, 3, … Cello 1, 2, 1, 2, 1, 2,… and count through the rallentando. When you can stay together through the four measures, playing them will be much easier.

Measure 57 is a potential finger problem. Practice playing the A-E-G as one gesture, stop, then start fresh on the D-F-C#, etc. Repeat these groupings many times, making the space between beats less and less, until it is seamless. This practice is an invaluable approach to any finger twister.

The D.C. with segno mark in measure 64 indicates a return to the beginning of the piece, not just to the top of page two. Unfortunately, there is no fine, and the movement has a double bar at the end of each section. It could be argued that this movement is in ABA form, and the end is the repeat of page one. However, most performers repeat both sections. My reasoning is the music is so good, I just want to do it again!

To bring variety to the repeat, the cellist can play pizzicato on the repeat of the second page, and the flutist can play a little lighter. When this is done, the cellist returns to arco on the last note of bar 60.

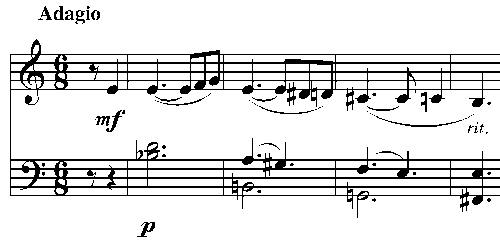

Adagio (eighth note = 138)

A descending pattern sets the mood of the movement, which seems to be both sultry and melancholy. There are several chromatically descending lines: the upper line of the cello part, measures 2-4, 6-8, and 9 in the flute, and 10-14 in the cello. Also, the A in measure two of the cello line and the F in measure three act as dissonant appoggiaturas that resolve to the G# and E respectively. Lean into and savor the dissonance of the first note. This appoggiatura tension and release continues in measures 10-14 and through the long descending line that ends in measure 20.

The flute line leaps up expressively three times against this, the most dramatic time in measure 27-28. The last five bars seems a haunting memory of a short movement that packs a lot of drama.

This movement benefits greatly from close attention to intonation, and a pure temperament will enhance the beauty and richness of the harmony. In other words, in certain instances you should play higher or lower than what would be standard on a tuner.

For example, in measure 1 (see example above) the dissonant augmented 4th – cello B flat against flute E – resolves to a perfect 5th when the flute moves to an F. Play the F slightly high to make the 5th pure. The flute’s E in measure two is equivalent to a perfect 4th above the cellist’s B. Lower the E slightly to narrow the 4th. Tune the flute’s C natural in measure 3 to the cello’s G, and the low B in bar four to the cello’s F#. Make sure the flute’s Gs are in tune with the cello’s harmonics in measures 10-13. In general, perfect fifths are played slightly wider, perfect fourths slightly narrower, and major thirds quite a bit flatter. For more information on using pure temperament see, The Tuning CD (www.thetuningcd.com), an invaluable tool for ear training and learning how to adjust pitches. As for vibrato, I suggest tapering any vibrato used as phrases taper, so that phrase endings have straight sound.

To keep the music flowing forward, practice the flute part in 34. This avoids the tendency to hesitate at the opening of each phrase or to leave ties late. Retain the 34 feel as much as possible, when returning to a 6/8 meter.

Vivo (dotted half note = 92)

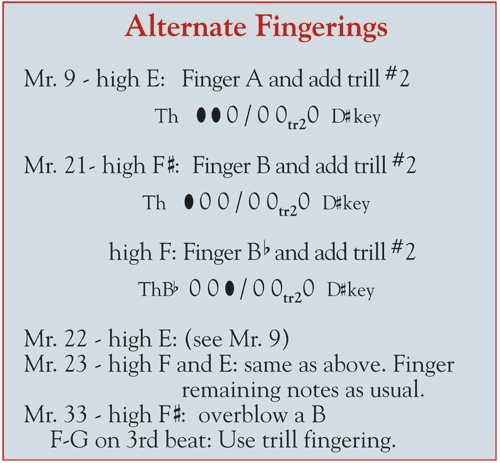

This tempo marking is extremely fast. I have never heard anyone play this movement at that tempo, but to get closer, alternate fingerings might help. The alternate fingerings suggestions in the box take time to incorporate, but when the music is speeding by, they work quite well:

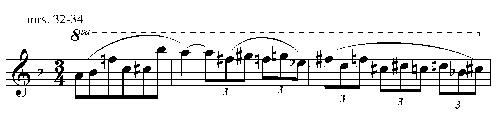

To avoid the tendency for fingers to stumble in this movement, anticipate leaving the ties, such as the one in measure 33, sooner and practice phrasing through the first three notes of the next measure (F#, D, F natural), stop, begin again on beat two and continue.

The same practice method works well in the following two measures. When playing in time, use the same phrasing approach even though you will slur through (though I often lightly, imperceptibly tongue the C# to orient myself and keep things clear).

This movement is a page turning nightmare. I suggest you copy the first and fourth pages and tape them on either side of pages two and three. At the a tempo in measure 126, play the four bars that finish the page and repeat back to the fourth measure of the movement. The music is the same until the end of measure 85. From there, have a copy of the last page of music on a second music stand. The trilled G flat on page 10, measure 177 is a misprint; it should be a G natural, just as it was the first time in measure 52.

Many flutists like to start the septuplet runs beginning in measure 38 on the slower side. They then accelerando through to the high-C climax. This interpretation is not marked but is hard to resist because of the excitement created by building both pitch range and speed.

With a good breath at the double bar in measure 88 and a soft dynamic level, (I like to think of this passage as a high-pitched whistle), you should be able to make it to the end of the E#-F# trills in measures 98-99. Some prefer taking a breath just before grace notes and using the grace notes as pick-ups to the double-tongued passage starting in bar 100. An alternative is to use them to end the trill gracefully, not as pick-ups to the double-tonguing passage. Take another good breath and enter with the cello on the downbeat. Think in four-bar phrases, as the cellist would benefit from doing in the opening.

I prefer to take catch breaths after the two-bar phrases, then leave out the second 16th on the Bb to breathe. Another solution is to leave the second 16th out of the downbeat of each 2 bar phrase (the “k”), and take a catch breath instead. Breathe again on the tied C#, and if necessary, after the A half note before the quintuplet in the a tempo.

The imitando fischi in toni ascendenti

On the last page, the music requires blowing into the flute fff, “as if one were warming up the instrument on a cold day.” I have found that when I change the angle slightly, I can get a more intense sound; blow directly into the tone hole on the low D, then raise the angle slightly up for the E, slightly higher for the F, etc. If you change the angle too much, you’ll lose the sound. Strive for precision in the scales that are ripped up at the end. Practice the runs in groups of three or four so that every note speaks in the excitement of the finale.

Editor’s Note:

A Memorable Performance

Flutist Richard Graef, assistant principal in the Chicago Symphony, and cellist Daniel Rothmuller, assistant principal of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, performed The Jet Whistle on Graef’s master’s recital when they were both students at Indiana University in the 1960s. The recital was on the first warm, humid evening in May. Although the temperature in the recital hall was high, the performers were well-respected, and students and faculty crowded in to hear them play.

The first movement went beautifully, but about a third of the way through the second movement, one of Rothmuller’s tuning pegs slipped. As double stops are prevalent throughout the Adagio, the cellist quickly found a substitute pitch on another string, and the performance continued.

A few measures later, a second cello string unwound. The slow whop, whop, whop of the string hitting the finger board could be heard throughout the recital hall. Again, Roth-muller searched and quickly found a way to keep the harmonies intact now using only two strings.

Finally, in the last five measures, a third string let go. The pair of performers, neither of whom seemed undone by their situation, finished the movement with two pitches, instead of the three prescribed – Rothmuller having only one of four strings in operation. Needless to say, there was a long period of cello tuning before the last movement. A reel-to-reel tape of that performance exists somewhere, now lost with time. Listening to it always provided a good laugh.