My father, Litchard Toland, was the ensemble librarian for the Eastman School of Music, so growing up in and around the Eastman School provided me with so many wonderful opportunities. I started ballet at the age of four at the ballet studio located in the annex there. Extraordinary student pianists from Eastman accompanied each class. I also was able to observe professional ballet dancers who were part of the ballet company, the Mercury Ballet. Unfortunately, my strong desire to be a ballerina was not supported by a great natural ability, but this exposure kindled my love of music. My favorite recollection is of sitting in the Eastman Theater, twelfth-row center with my mother for my twelfth birthday to see the Royal Ballet with Margot Fonteyn. I also spent many, many hours backstage at the theater with my father, as he was responsible for the music for all ensemble concerts and those for the Rochester Philharmonic. By the time I was a teenager, I had seen numerous local concerts as well as performances by the Philadelphia Orchestra, Boston Symphony, Bolshoi Ballet, and many others. In short, thank goodness for my Dad’s position.

How did you get started on the flute?

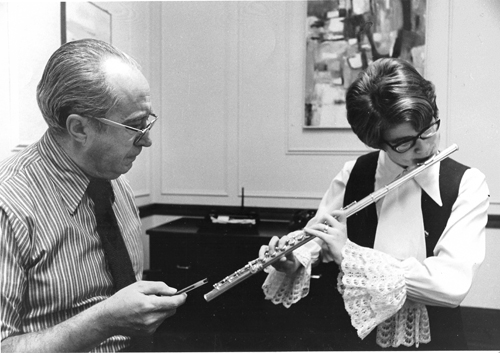

Like many flutists, I started in the public school music system. When I was a freshman in high school, I began private lessons in the Preparatory Department at Eastman. During my second year, I began lessons with Patricia George. At the time I was not really sure that playing the flute was for me and had even asked my father if I could quit. Many years later, I found out that my father and Patricia had an agreement to give my lessons six months and see if we could turn things around. This was a definite turning point for me. After two years of intense work on fundamentals, etudes, and solo repertoire, it was arranged for me to do an early audition for entrance into Eastman to study with Joseph Mariano (below), and I was accepted. I spent five fantastic and challenging years at Eastman where Joseph Mariano encouraged me to develop more sensitivity and individuality in my playing. I also found inspiration from the other flute students there during this time, including Leone Buyse, Paul Britten, Bonita Boyd, Fenwick Smith, Robert Goodberg, Damian Bursill-Hall, Linda Christen-sen Wetherill, Diane Smith, Jan Harbaugh Angus, Janet Ferguson, Randy Hester and Glennda Dove to name just a few.

My college teaching career started with a one-year sabbatical replacement at SUNY: Fredonia which gave me experience teaching flute at the college level and a reality check into the inner workings of a music school. Next I taught at Roger Williams College in Bristol, Rhode Island. After the first semester, I was appointed flute professor at Ohio State where I stayed for four years. I realized that I needed a doctorate, so I applied and received a doctoral fellowship to Ball State University where I studied with one of the unsung heroes of the flute world, Paul Boyer. Two years spent with him expanded and solidified pedagogical ideas for teaching much of the standard flute repertoire. His style of coaching was exactly what I needed at the time.

What did you learn from your doctoral studies?

Having been in the professional world for a few years before pursuing my doctorate gave me a clearer idea of what I wanted out of an advanced degree. I knew that a college teaching career was perfect for me. I wanted an approach that would not only help to perfect my skills, but would also allow for discussion of teaching ideas for practicing, approaching etudes in a methodical but musical way, and for plugging some of the holes in my knowledge of standard repertoire that I would teach in the future. Mr. Boyer gave me creative and clever ideas to take a piece apart, find ways to extract concepts to focus on outside of the piece, and to bring life to some of the intermediate and moderately advanced repertoire. One task I remember in particular was going through the entire Flute Music by French Composers book performing each solo and then discussing what typical problems might occur and some ideas on how to solve them.

What led you to Texas State?

While I was working on my doctorate, I watched for college flute job openings. In my second year the position at Texas State was advertised. I was hesitant at first about applying because I still had my dissertation to write and I was not sure about moving to Texas, having grown up in Rochester and with my family still there. Paul Boyer encouraged me to apply. Knowing how few and far between college teaching jobs are, I decided to throw my hat in the ring. Thirty-two years later, I am very glad I did.

For the job interview I performed a half-hour recital, taught three students of varying proficiency levels, had interviews with the search committee and upper administration, and had a question and answer session with students. After a grueling two days, I was offered the job. As I recall, they gave me a week to make the decision. After completing my coursework that summer, I packed and headed to Texas.

What was your dissertation topic and how did you complete it while teaching full-time?

My topic was The University Flute Choir: A Study of its Viability as a Performing Ensemble and Instructional Medium with a Compendium of Recommendations and Warm-up Exercises. Fortunately, I had already chosen the topic and written some of it before I left Ball State. For the first few years at Texas State, my top priority was building a studio and getting settled into my college position. I spent summers researching and writing the dissertation. It was a difficult task to complete and took seven years plus a little pressure and motivation from my department chairman. I now can definitely see the advantages of finishing the dissertation before getting a job.

However, this research led to the eventual publication of The Flute Choir Method Book (published under the name Adah Toland Mosello by ALRY Publications), which explores, through warming up activities, the technical and musical aspects of performing in a flute choir.

What has led you to stay at Texas State for 32 years?

I really enjoy working with the students at Texas State. They are wonderfully receptive, and we establish close relationships. The location of the school provides many performing opportunities for me. I have been principal flute of the Austin Lyric Opera Company since its inception in 1987, and the school’s location between Austin and San Antonio allows me to be a substitute and extra flutist with both the Austin and San Antonio Symphonies. In the summer, I am principal flute with the Victoria (Texas) Bach Festival Orchestra. This week-long festival features performances of chamber music, orchestra music, and usually one large-scale work with Conspirare, an Austin-based professional vocal ensemble.

Do you have a weekly group flute class?

My flute seminar meets once a week for 90 minutes which gives students the opportunity to work on various technical and musical aspects in a group setting and to perform for each other. Each semester they focus on one playing technique. For instance, last semester they concentrated on dynamics. In the flute seminars, students each performed a melody from Trevor Wye’s Practice Book for Flute, Volume 4: Intonation and Vibrato or Marcel Moyse’s Twenty-Four Little Melodic Studies with Variations adding their own dynamics. Then the class identified and discussed the dynamic choices.

This semester the focus is on intonation. I divided students into pairs in order to make a pitch tendency chart. While one student played from B4 to D7, the other filled in the chart, and then they switched jobs. They have found the biggest trouble spots and are honing in on correcting them with warm ups based on harmonics, slow melodies, triads and scales. I plan to repeat the process two more times this semester.

Since performance anxiety seems to be a universal issue, each student performs for one minute in the seminar each week. They dress in recital attire and practice proper stage etiquette. This frequent exposure to a performance situation is reaping benefits already as students have commented that they feel more relaxed and in control. They also make written comments for each person who plays an extended performance in class in addition to the usual verbal ones. I feel both ways of commenting help students articulate their ideas and formulate their own teaching style.

Each term students concentrate on one style period, rotating through the music of the Baroque, Classic, Romantic, examination pieces from the Paris Conservatory, and music of the 20th and 21st centuries. One seminar class is devoted to an overview of the time period and basic performance practices. Each student chooses a specific composition, researches it, and then performs on a studio recital. In addition, they also explore technical and tone exercises, etudes, and a variety of solo works.

Based on a student’s suggestion a few years ago, upper level and graduate students have the opportunity to do an individual project each semester. This has turned out to be enjoyable and informative for the student, the studio, and me. Some of the innovative projects completed by students include:

• Developing a CD set of two to three recordings of most of the standard pieces of repertoire accompanied by an Excel chart listing the piece, composer, performer, and style period. This has become a handy resource for the studio.

• Learning Celtic flute and performing for the flute seminar, giving a brief description of some of the playing challenges and performance practices.

• Arranging Christmas carols in duet or trio form for beginning flute players.

• Developing a PowerPoint presentation discussing the differences between music education in South Korea and the U.S. by one of my Korean students. (This project also involved some culinary delicacies.)

• Presenting a detailed outline of the process of applying to graduate schools, including details about auditions, preparing the various required pieces and excerpts, arranging audition dates, etc.

• Making original compositions and arrangements, including short flute choir pieces, solo pieces, and interesting chamber pieces.

• Keeping a journal about teaching experiences for a semester. Many of my students teach several students of their own, so one tracked assignments and progress and presented this with a video of her teaching for the studio to observe and critique.

• Interviewing and writing synopses of several women conductors, including their training and aspects of their current positions.

The projects vary incredibly each semester, and I am always curious to see what my students choose to explore. This adds another dimension to their development and gives them the freedom to spend time researching topics of their own choosing.

How did you come to study with Jean-Pierre Rampal and Marcel Moyse?

I had the opportunity to spend two summers studying with Rampal, one in Nice, France and the other in Stratford, Ontario. These two masterclasses profoundly influenced my development as a flutist and as a teacher. I returned to Nice a few years later with two of my flute students from Ohio State. Hearing Rampal play on a daily basis for weeks at a time was an incredible and life-changing experience; his exuberance and zest for life was infectious.

Rampal taught each day for six to seven hours with a break for lunch. The level of playing was astoundingly good, and I heard pieces in the repertoire that I did not know. Joseph Mariano had a rather quiet, dignified demeanor. His teaching style was quite thoughtful and rather serious in approach and always conveyed a sense of purpose, concentrating on sound, style, and nuance. The atmosphere in Rampal’s class was very different. He was bigger than life, incredibly energetic and very demonstrative. My playing was quite timid at times, and his sparkle was just what I needed to bring me out of my shell. I can remember several occasions when he stood right in front of my music stand and shouted, “Joue!” (Play!) “Joue la Flûte!” with the most amazing twinkle in his eyes. Both in my lessons and with the other flutists, he concentrated mostly on projecting musical ideas, exaggerating nuances, finding the character of the piece, and using all of the senses to explore the possibilities. This was not a place to work on fundamentals; this was an opportunity to really grow and move to the next level of independent musicianship.

I also attended a week-long masterclass with Marcel Moyse in Vermont. The experience of just being in the same room with such a great master cannot be duplicated. The flute masterclass was half of the day, and a woodwind chamber music class was the other half. Again I was exposed to such chamber pieces as the Mozart Gran Partita, the great Beethoven Octet, and Chansons et Danses by d’Indy. Watching Moyse come alive in these classes (he was in his 80s at the time) was magical. I remember a couple of specifics that have stuck with me. One young lady played Syrinx and was a bit too free with the rhythm, so Moyse walked up next to her as she was playing and tapped eighth-note subdivisions throughout the entire piece. The place where the class was held was quite chilly in the mornings, and I remember him taking my flute out of my hands as I was blowing warm air into the embouchure hole. He turned my flute upside down and blew in the footjoint explaining that the low register would still be flat if the end of the flute was cold. There were so many phrasing ideas that he explained with the most beautiful metaphors.

What do you look for in a prospective student?

I search for potential. First and foremost, I look for a good sense of rhythm and pulse. Additional qualities include a well-developed, centered sound with a natural-sounding vibrato, a reasonably comfortable playing position, good posture, and a basic control of technical and articulation aspects of flute playing. When possible, I encourage students to contact me to have a mini-lesson before their audition. This gives me an opportunity to see if they have a willingness to try new ideas, and seem self-motivated. I also look for students I think will fit into the program and will get along with other students in my studio as I try to foster an atmosphere of support and mutual encouragement. This is as important to me as their playing, and it makes the day-to-day environment more comfortable, non-competitive, and healthy.

What do you focus on in the first lesson with new students?

At the first meeting, I take a flute history, like a physical with a new medical doctor. I find out their knowledge of scales and warm-ups and then have them play while I watch for posture, hand position, embouchure, breathing, use of vibrato, sense of phrasing, ability to double tongue and of course their sense of rhythm. I jot down my findings and then usually start with breathing and support.

I have several good analogies that work well for support, but the best one is to think of a bicycle pump. After securing your feet on the base, lift the handle. As air is drawn into the tube, there is no resistance. As you press down on the handle, there is resistance because the air is being compressed into a smaller space as it is pushed into the bottom of the tube, into the small hose and then into the tiny opening in the tire. Our body works like this only upside down. We let the air in with no resistance, then a firm pressure moves the air from the lungs into the smaller space of the windpipe and then through the tiny hole in the lips. The resistance needed to let the air out slowly but with energy is created by the air moving from one space into a smaller and smaller place.

Posture comes next. I tell students to get a slight turn in the head with the flute slightly forward and the right arm lifted directly up from the side. Since most of my students come from a marching band background, this change of position needs to happen right away to assist in tone production and better support.

Embouchure would be next on the agenda. I work with students to develop a natural, relaxed position with slightly firm corners and flexible lips. The most important thing is to find the groove in the chin where the curve of the embouchure plate can rest. I liken it to two spoons being cradled together. This seems to place the embouchure plate in a good spot so that the right amount of the hole is covered and there is room for slight changes between registers.

What types of pieces do you begin with when students first come to you?

Most students have gaps in their knowledge of the intermediate repertoire. I think many times they have been encouraged to jump into difficult repertoire too soon, without establishing good tone and phrasing concepts by playing less complex pieces such as Handel Sonatas or pieces from Cavally’s collection Twenty-four Short Concert Pieces. Working on Baroque repertoire gives them the opportunity to explore the effects that modulation, sequence, use of non-chord tones, and phrase structure have on breathing, tone colors, and articulation. The solos in the Twenty-four Short Concert Pieces move into Romantic repertoire to develop more overt expression, control of extended range, and advanced technical skills. I especially like the Molique Andante to expose students to more complex rhythms. Patience is required to understand that stepping back to analyze and perfect good playing concepts will pay off in the long run. My younger students hear the more advanced students performing repertoire such as Prokofiev, Taktakishvili, Liebermann, or Reinecke and know that they started with the same pieces and that the process pays off over time.

* * *

Double Tonguing Exercises – pdf

Flute Notebooks

Each semester, my students are required to keep a notebook with the following:

1. Goals: short and long term

2. Weekly lesson assignment sheets

3. Practice routine outline(s)

4. Weekly Practice Chart: a brief daily log of practice sessions.

5. Notes from lessons, including written reviews of weekly lesson recordings

6. Handouts: schedules, syllabus updates, pertinent articles, exercises, etc.

7. Historical overview forms for solo repertoire: students are required to complete a brief historical overview form for each solo studied in the semester. These are due at the completion of each solo work and then added to the notebook.

8. Evaluation Forms: After each studio recital, students listen to the recording and fill out an evaluation form with about fifteen questions, ranking them from 1-10, including intonation, control of technique, vibrato, rhythmic stability, etc.

After students have completed the Upper Level Competency Exam after four semesters of study, practice logs are no longer required. Upperclassmen choose a topic for an individual project.

Former students often contact me to tell me how much the notebooks helped them and how many times they refer to them in their own teaching.