.jpg)

The bass trombone occupies an inconsistent place in many school band programs. While some large programs always have at least two or three bass trombonists, in others the instrument is unknown or is used only by the occasional student who takes it up at his own initiative. Many an instrument room contains an aging bass trombone that is played only on the rare occasions when a director deems it necessary for a certain piece, and then by a student with minimal training and even less knowledge of the instrument’s characteristic sound. These latter scenarios are unfortunate, because a well-played bass trombone greatly enhances the tonal palettes of both concert and marching bands.

The Bass Trombone’s Role

When considering the role of the bass trombone in concert and marching bands it must be admitted that this instrument is a luxury. Even concert band works in which the lowest trombone parts extend well into the trigger register can be negotiated reasonably well using a tenor trombone with an F attachment. Examples include Movement IV of Gustav Holst’s Second Suite in F.

and Eternal Father, Strong to Save by Claude T. Smith.

However, the rare piece that includes a B1/Cb2, such as Chance’s Incantation and Dance, will require using a false tone or adjusting the F attachment tuning slide to E if the lowest part is to be played on a tenor trombone.

Although the bass trombone is not absolutely necessary to hit the notes in low third and fourth trombone parts, it is essential if those notes are to be produced with the best possible sound. The larger bore, bell, and mouthpiece of the bass trombone enable the player to extend into the lowest part of the range while maintaining a characteristic trombone timbre. Moreover, a diligent player who specializes in the bass trombone will have spent much more time developing skills in that part of the range than a less diligent tenor trombonist who is placed on the third part because his audition landed him at the bottom of the section.

The overall band sound should also be considered. The desire to hear a seamless, homogeneous brass section sound from the trumpets down through the tubas can be thwarted by the large difference in timbre between the tenor trombones and the euphoniums. The warmer and darker, but still characteristically trombone-like, sound of the bass trombone provides a bridge between the sounds of the tenor trombones and euphoniums. In this respect, using a bass trombone on the lowest trombone part is beneficial even for pieces in which the tonal range does not necessitate the larger instrument. I have observed similarly good results when using bass trombones in marching bands, even though the lowest trombone parts in those groups rarely extend very far into the low register. The bridging effect of the bass trombone between the tenor trombones and the lower brasses applies here also, and the result is rather pleasing.

In jazz bands the bass trombone moves from luxury to necessity. Even intermediate-level jazz band charts will call for excursions into the valve and pedal registers in the lowest trombone parts. The frequency and intensity of these notes only increase as the music becomes more advanced, and a double-valve instrument is almost certainly required. Likewise, in schools that have orchestra programs that borrow wind and percussion students from the bands, a bass trombone will be needed on the lowest part because of both range requirements and timbral considerations.

Choosing Bass Trombonists

Having determined that placing one or more of the band’s trombonists on bass trombone will benefit the ensemble, the next step is to decide which students to consider for the larger instrument. (There are instances when players of another instrument, especially euphonium or tuba, might be considered for a switch to bass trombone as well.) Here are some identifying markers of trombone students who might make good bass trombonists:

The student is of sufficient physical stature to handle the weight, air, and embouchure requirements of the bass trombone. The bass trombone is a large and heavy instrument, requiring significant upper body strength to hold and to manage. Moreover, the amount of air required is significantly greater than that required for the tenor trombone, because of both the size of the instrument and the tessitura being played. Finally, even the smallest mouthpieces that yield a satisfactory bass trombone sound are significantly wider and deeper than most tenor trombone mouthpieces, requiring a student with large and strong facial features. The bass trombone might be an especially good option for students who seemed more suitable for trombone than for tuba as beginners, but whose embouchures have filled out as they have gotten older. Bass trombone should by no means be limited to large students, but the physical requirements are significant and should be taken into account when considering students for the bass.

The student should also have a good characteristic trombone sound. While the bass trombone is a specialty instrument, it is still a trombone and should sound like one, only larger. Remember, one of the primary reasons to include the bass trombone in the wind band is that it is a bridge between the timbre of the tenor trombones and that of the lower brasses. A student who is incapable of producing a full sound on the tenor trombone will certainly be unable to fulfill this role with the bass trombone, especially given the latter instrument’s greater air and embouchure requirements.

The student should enjoy and perhaps be strongest when playing parts in the middle and lower registers. This is not the same thing as saying the student is weak in the upper register. Moving to the bass trombone does not eliminate all requirements for high range development, and thus a student who struggles in that area on the tenor trombone, especially if the struggles are due to lack of effort, will not find the bass trombone to be a panacea for this difficulty. However, a student who truly excels in the lower register without neglecting the upper range might find the bass trombone to be an excellent fit. In a few cases, the larger mouthpiece actually helps with the student’s upper register, which will lead the newly minted bass trombonist to soon having an exceptionally large range.

The student should also be able to think and work independently. While the bass trombone is still a trombone and even shares most of the same slide positions as the tenor, there is still a learning curve for the student who switches from tenor to bass, most especially regarding slide positions using the second valve. Whether because of insufficient class time for individual attention, unfamiliarity with the bass trombone on the band director’s part, lack of available private instructors, or a combination of these factors, students who move from tenor to bass trombone often have to teach themselves the new instrument in large measure. The student who is a good candidate for bass trombone is thus one who is able to take the instructional materials provided and run with them in an independent manner.

The student should be one who wants to take up the bass trombone. This is an important factor that should not be dismissed. Although it is sometimes necessary to persuade otherwise uninterested students to change instruments in order to improve the balance of the ensemble, such changes are most successful when the student is willing to make the switch and even enthusiastic about doing so. The switch from tenor to bass trombone should ideally be made only by students who truly desire to make that change.

Although there are a number of physical and musical traits typical of trombonists that can make good candidates to move to bass trombone, there are some characteristics that should not be used as criteria when choosing students to switch. First, the students currently playing third trombone in the band are not necessarily the ones who should be considered for bass trombone. If a student is sitting at the bottom of the section because of lack of practice, chances are that switching from tenor to bass trombone will do nothing more than exchange a mediocre tenor trombonist for a mediocre bass trombonist.

Secondly, while a student who struggles with the upper register might be a good candidate to move to bass, this is not true in every case. When compared to tenor trombone music, the upper range requirements for bass trombonists are not reduced nearly as much as the lower range requirements are increased. In other words, bass trombonists are often required to have the largest tonal range of the entire trombone section, and this makes the transfer of a student from tenor to bass trombone in an attempt to evade a range problem a potentially foolhardy choice.

Another preliminary consideration is when to move students to bass trombone. Given the multiple shared slide positions and techniques between tenor and bass trombones as well as the substantial size and weight of the bass, I do not advise moving a student to the bass trombone before high school.

Choosing Equipment

In recent years the number of commercially available bass trombones has increased dramatically, with a wide range of options for bore and bell sizes, mouthpieces, valves and valve configurations, and other characteristics. These developments are great for the bass trombone community but can make choosing instruments and mouthpieces a daunting task for students who are new to the bass trombone. There are broad guidelines that directors and students should consider when choosing a mouthpiece and instrument.

The choice of mouthpiece might be more important than the choice of instrument. Given the desire to produce a big sound as quickly as possible, directors or students might be tempted to purchase the largest bass trombone mouthpiece they can find, but this is almost certainly a recipe for disaster. The dramatic increase in air and embouchure requirements brought about by the largest mouthpieces will likely be overwhelming, and the sound produced will be more similar to a poorly played tuba or euphonium than a trombone. A mouthpiece with a cup diameter of approximately 27mm, for example the Bach 1.5G or Schilke 58, is big enough to provide the desired timbre without being overwhelming because of excessive diameter or depth. Larger mouthpieces can be considered once a student has adjusted to the bass trombone, but the sound produced with mouthpieces comparable to those I have mentioned is satisfactory and moving to something larger is not a necessity.

Likewise with instruments, bigger is rarely better. Bass trombones can be purchased with .562"/.578" dual-bore handslides and bell diameters as large as 10.5". As with the largest mouthpieces, these gargantuan instruments most likely will not yield the desired sound. High school bass trombonists should stick with a more reasonable .562" bore instrument with a 9.5" bell. Such instruments are perfectly capable of yielding the darker and warmer sound that is desired while still maintaining a trombone character.

The choice of valves and valve systems is also important and might be the most confusing aspect of considering bass trombones. First of all, only double-valve bass trombones should be considered. Single-valve instruments are not fully chromatic in the lower register (B1 cannot be played on a single-valve instrument), and the second valve, once mastered, greatly enhances facility throughout that part of the range. Double-valve bass trombones are available with both independent and dependent setups. In both setups, the first valve is an F attachment, just like that of the tenor trombone, and in both setups engaging the two valves together almost always lowers the first-position fundamental pitch to D. The difference is that in the independent setup both valves are mounted to the main body of the instrument, so that the second valve can be used independently (yielding a fundamental pitch of Gb), whereas with the dependent setup the second valve is mounted to the first valve’s tubing, and can only be used in combination with the first valve.

Both systems have their advantages. The independent setup provides more alternate slide position options, while the dependent setup sometimes feels more open when the valves are not engaged, since the player is not always blowing through two valves. The choice between independent and dependent setups is entirely at the discretion of the director and student.

Bass trombones can be purchased with rotary valves, axial-flow (or Thayer) valves, or a number of other proprietary valves. The differences are usually limited to the subjective feel and response experienced by a player and not readily perceived by listeners. When considering instruments for a beginning bass trombonist, and especially if the school is purchasing the instrument, the most cost-effective valve type (usually rotary valves) is usually the best choice.

The Transition to Bass Trombone

When I have visited high school band rooms and seen students struggling with the bass, the two most common problems have been poor mouthpiece choice (usually too small, such as a large-shank tenor trombone mouthpiece, but occasionally too large) and ignorance of how to use the second valve. In many cases the slide position charts available in band method books and other materials marketed to school band directors also lack information on the second valve, so both directors and students are lost when trying to determine how to use it. Happily, some of the method books listed below include slide position charts for the double-valve bass trombone. Position charts and warm-up exercises are also available on my website: www.olemiss.edu/lowbrass

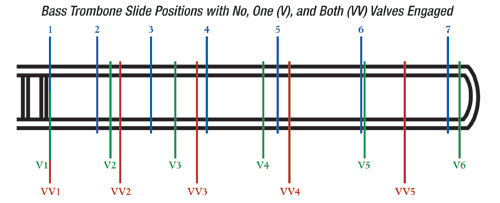

On the bass trombone, the slide positions when both no valves and the F attachment are engaged are the same as those of the tenor trombone. As usual, when the F attachment is engaged, the distance between slide positions lengthens so much that there are only six positions possible when that trigger is used. The locations of the positions using an independent Gb attachment are similar to those using the F attachment, and when both valves are engaged the distance between slide positions increases even more, so that the instrument then has only five positions. While fine-tuning intonation determines the precise location of each position, the diagram above shows the approximate locations of the slide positions with no valves, one valve, and both valves engaged.

The chart shows that sixth position with one valve engaged is precariously close to the end of the slide but does not appear to be as far away from fifth position as it should be. The handslide would need to be a little bit longer to yield a true sixth position with the valve engaged. This is one more reason that the double-valve instrument is preferable.

Once a student has a basic understanding of how the bass trombone works and the location of its slide positions, the following method books can help to increase facility on the instrument. Although these studies are best undertaken with the guidance provided by regular private lessons, students can also work through these independently with some success.

The Double-Valve Bass Trombone by Alan Raph (Carl Fischer). Following introductory materials that provide a basic understanding of the bass trombone, the book quickly progresses to etudes and exercises, which will to increase the student’s overall facility and familiarity with the valves used individually and in combination. This is a fine first method book for a diligent student who is transitioning from tenor to bass trombone.

The F&D Double Valve Bass Trombone: Daily Warm-Up and Maintenance Exercises by Paul Faulise (PF Music). This book contains exercises that can be used for daily warm-ups and to increase understanding of the valves and how to use them. The difficulty ranges from simple long-tone exercises to advanced slurring and articulation patterns using both valves.

70 Progressive Studies for Bass Trombone by Lew Gillis (Southern). This older method book is annotated for use with a single-valve instrument but can also be used to develop facility with the double-valve bass trombone.

Melodious Etudes for Bass Trombone by Marco Bordogni, arranged by Allen Ostrander (Carl Fisher). Ostrander has transcribed several of the etudes from the well-known Bordogni/Rochut method into keys suitable for bass trombone. Like the Gillis book, this book is annotated with a single-valve instrument in mind, but is equally useful for double-valve bass trombones and is a great tool for developing smooth, lyrical playing in the lower register.

24 Studies by Boris Grigoriev, arranged by Allen Ostrander (International). These musically pleasing etudes make thorough use of the valve register of the instrument. This is a common source of bass trombone audition etudes for all-state bands.

New Method for the Modern Bass Trombone by Eliezer Aharoni (Noga). This book is similar in format and intent to the Alan Raph book, but the etudes here are more difficult (and more interesting).

In addition to these materials, be sure to direct students to recordings of professional bass trombonists so that they can begin to develop a concept of the instrument’s characteristic sound. There are tremendous resources available, including YouTube and other audio and video streaming websites as well as commercially available recordings.

Summary and Conclusion

Most band programs can get by without bass trombonists, but the instrument should not be viewed as a mere luxury with limited benefit. Adding even one bass trombone will yield improved tone quality on the lowest trombone parts in concert bands, a more seamless brass section timbre in both concert and marching bands, and the necessary bottom trombone voice in orchestras and jazz bands. Implementing the foregoing suggestions on selecting, equipping, and transitioning students to the bass trombone will provide a good start to any director seeking to incorporate this extremely useful instrument into the music program.