At a recent jazz workshop, a woodwind doubler was asked how he worked a melody before improvising on it in a public performance. He answered that he had about 350 ways to practice the melody before he felt comfortable improvising in public. As he explained his method, I was struck at how similar his ideas were to those of a classical musician.

One More Time

Band directors and private teachers commonly ask students to play something “one more time” followed by “just one more time.” As a student I sensed that without more specific instructions the group would not improve musically. The passage became cleaner rhythmically and easier technically through the repetitions, but the expressive element was not there. The players did not have a plan.

Getting a Plan

This has been of concern to musicians throughout the ages. For example, in the Johann Joachim Quantz book On Playing the Flute, a section called On the Manner of Playing the Adagio addresses the topic. His principal concern is with how ornaments should be realized according to the style of the time. He also has a section on how to accompany these melodies.

In Part 7 of the Taffanel et Gaubert Complete Method, Taffanel offers suggestions for interpreting the slow movement of Bach Sonata in B Minor, BWV 1030 and the Gluck Minuet and Spirit Dance and advises putting short descriptive sentences above each measure of the score. Instructions for the first section of the Bach slow movement include phrases such as “The first bar calm and without nuance, a very slight crescendo, slight accent on the first grace notes – leaning a little, expression on the G but avoid any emphasis and remain simple, trill without termination, broaden and let the tone fall – finish very simply p without rallentando.” While these phrases are interesting, there are no broad ideas about melodic shaping that a player can use when approaching other melodies.

The great French oboist Marcel Tabuteau had a numbering system in which each note was assigned a number by importance. Laila Storch, the first woman oboist to graduate from The Curtis Institute of Music wrote a biography of Tabuteau (Marcel Tabuteau: How Do You Expect to Play the Oboe If You Can’t Peel a Mushroom?) in which she discusses this system. Tabuteau encourages oboists to think of each note as if bowed like a string player – up bow and down bow. Flutist William Kincaid, who played principal flute next to Tabuteau in the Philadelphia Orchestra and at the Curtis Institute, taught this down/up system as well as note grouping. In note grouping the idea is that all notes lead to one. So, rather than playing four sixteenth notes 1234, the flutist plays 1, 2341.

In De La Sonorite pages 24-27, Marcel Moyse offers a three-step process to practice developing an interpretation using melodies by Handel, Bach, and Massenet. Moyse instructs:

“1. Play the andante right through with a soft tone, pianissimo. To use an analogy with drawing, this will as a whole constitute the ‘outline.’ Carefully observe the tempo – eighth note = 60, no vibrato, great attention to the values, breaths and slurs; take great care that in slurring over large intervals there is no accent. Here the melody will emerge, so to speak, in all of its nakedness.

2. Play the andante over again twice, still bearing in mind the above remarks, but this time including the dynamics indicated. This will still represent the ‘outline,’ but now with contrasts of light and shade.

3. Play it over again twice, as before, but now with expression.”

Moyse goes on to say “This manner of practicing is long and sometimes arduous, but it has the advantage of providing time for reflection. The rational mind has time to take charge over the instinct, to direct one’s temperament without repressing it, and in my opinion any interpretation of beauty must be based on this happy balance.”

The Takeaway

The above information offers ideas on realizing ornamentation, flowery sentences to describe the atmosphere of the measure, a numbering system, a note-grouping idea, and a process of removing all expression to reveal the outline and then adding elements back in. Professional flutists have sought more. Another common practice is listening to recordings and imitating what is heard. In rehearsals, colleagues share observations about taking time in certain places or emphasizing a note by lengthening or coloring with vibrato. Unfortunately, most students stick with the “play it again” method for too long. If a jazz musician has 350 ways to work a melody, perhaps flutists should have a list too.

Advice from a Master

My teacher at the Eastman School of Music was Joseph Mariano, a student of William Kincaid. Mariano often closed a lesson by asking if I had an ensemble or chamber concert that week. If so, his closing remark as I was departing his studio was “Turn a phrase for me.” This always struck me a bit odd because he, who always spoke eloquently, was instructing me to turn a phrase – meaning a single phrase for him. Why would he not say, “Play musically tonight,” meaning to play all the phrases well.

It took me some time to realize that phrasing is challenging, and it was a good night if one phrase turned out as I intended. This led me to write down general phrasing ideas as I discovered them. I continue to do this more than five decades later. Many of these are familiar; however, having them in an organized list may make the ideas easier to pass on to students.

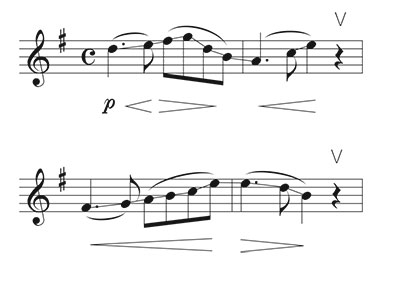

Use the melody below from 40 Melodies by A.M.R. Barret (A Complete Method for the Oboe), No. 7 in G major to explore phrasing ideas. Barret wrote these melodies as instructional material for his oboe and bassoon students. The oboe took the treble part and the bassoon the bass part. If you can read bass clef, this duet works well with C flute and bass flute. If you prefer to use alto, remember the alto flute is pitched in G so the part will have to be transposed.

Playing from a score like this offers many advantages. Being able to see what the other part is playing improves rhythmic ensemble. Because of this, many players note cues in their parts when the bass line is not included. Since intonation is calculated from the bass part up, seeing and hearing the bass line helps players know where to place each note so it is in tune. When looking at the score, it is easier to determine the non-chord tones. Non-chord tones (passing tones, neighboring tones, appoggiaturas, and suspension) are often the notes to be brought out in the musical line.

What is a Phrase?

A phrase is a musical sentence or statement. Phrasing is bringing these sentences to life. Phrase lengths can be varied in length. The melodies from 1750 onwards are usually based on groups of eight bars that may be subdivided into two- or four-bar phrases. The next most frequent phrase length is six measures. In contemporary music some composers favor asymmetrical phrase lengths. Whatever the phrase structure is, players should mark all the phrases in the score. Wind players need to breathe and most of the time the breath is taken with the phrase ending. Mark phrases by using a V.

40 Melodies by A.M.R. Barret (A Complete Method for the Oboe), No. 7 in G major

.jpg)

What is the Shape of the Phrase?

There are five shapes: mountain, valley, going up, coming down and some sort of turn resembling a gruppetto. To determine the shape, draw a line from one note head to the next in each phrase.

Using only the first note of the phrase, play the phrase with this one note going to the high point (mountain shape) or low point (valley shape). By playing only one note, it will be apparent if you are shaping the phrase well with the air stream.

.jpg)

After you are pleased with the results, play the contour using the printed notes. Notice what are now called crescendo and diminuendo marks, Barret called nuances. If you think like Barret did, these marks show where to lead with the air stream and where to back away. Students often ask about the crescendo marking in bars two and six. Normally most would diminuendo the last two notes of the phrase, so they wonder why Barret put a crescendo there. It was to help the player phrase by four bars rather than by two. This was a way of carrying the line.

From the Baroque era on, the strength of the beat concept is something composers consider. As most Baroque music was for dancing, the first beat was strong so dancers would know when to land their feet. The music of the Romantic period was about singing so melodic lines surged towards the first beat of a measure. In the first case, musicians refer to coming away from beat one (getting softer), and in Romantic music they think of it as leading or going to beat one (getting louder). These two gestures are used on most music.

Two-Note Slurs

The Taffanel et Gaubert Complete Method begins with teaching flutists to play whole notes with a steady air stream. Three pages later slurring of two notes is introduced. After a brief discussion of intervals, there is a section on Legato (Du Legato ou Coulé) with this exercise:

.jpg)

Here, Taffanel is concerned about the connection of the two notes. He writes “It is chiefly from the study of legato (the slur) that the student will gain perfect equality. The smallest inaccuracy appears at once in the use of legato. When practicing legato the student must take great care to move the fingers together when several are required to move at the same time.” By making the second note or the release note of shorter value, Taffanel is also concerned with the note ending. Since the Baroque era, string players have been instructed to make the second note of a two-note slur softer than the first note. In the Barret No. 7 example, notice that this idea may be applied in measures 8, 9, 10, 13, 26.

Balancing of Phrases

Throughout No. 7, the two-bar phrases are balanced off by pairs. This leads one to question whether phrase 1 (bars 1 and 2) is more or less important than phrase 2 (bars 3 and 4). Play it both ways and then select the one you like best. Feel free to change your mind from one practice session to the next. It might seem clearer what to do in phrase 5 and 6. Since phrase 6 (bars 11 and 12) has a higher range or tessiture, play it slightly louder than phrase 5. There is not right answer at this point. You just want to be sure you are playing a way on your search to the way.

Repeated Notes

In bars 4, 12, 13, 15, 16, 17, and 25 there are repeated notes. Be sure they have an articulatory silence between them, so the rhythm is clearly heard by the listener. Think about whether the first or second note should be louder. To find the answer, look at the strength of the beat rule. In measure 4, the E will be louder than the E in measure 3. In measure 14, the D natural on the fourth beat is a pickup into the D in measure 15, so it should be softer.

Syncopation

Besides repeated notes, syncopated notes should be separated. See bar 22 as an example. All of these pitches should be played slightly shorter in duration than written. This is true in bar 24 too.

Tessitura

Look for the highest notes. The C’s in measures 15 and 24 are on weak beats while the C in measure 25 is on a strong beat. The C on the strong beat is most important. Knowing where the highest note in a piece is shows the climax or focal point in the composition.

Working the Melody

After completing the analysis above, work on the melody, so you not only have the analytical skills but also the technical skills to play it well. Work in sections (mm. 1-8, 9-18, or 19-26). One idea would be to take a section a day and work through the following:

Repetitions

This will help you learn the notes. By repeating each of the following exercises with a different syllable, you are slightly changing the position of the tongue in the mouth. (A similar exercise to do is to play the passage with each of the vowel sounds as this too slightly changes the position of the tongue in the mouth.) A change in position of the tongue may improve your overall sound plus this work will enhance double tonguing for another day. Use a tuner to help pinpoint the pitch tendencies of each note.

1. Tongue each pitch four times with the T. Repeat using K and Hah.

2. Tongue each pitch three times with the T. Repeat using K and Hah.

3. Tongue each pitch two times with the T. Repeat using K and Hah syllables.

4. Play melody with T on each pitch in rhythm.

5. Play melody with K on each pitch in rhythm.

6. Play melody with Hah on each pitch in rhythm.

Wiggles

1. Trill between two notes in sixteenth notes with regular fingerings for eight counts. Metronome should be set to 96 for four sixteenths. For example, trill from D to E, then E to F#, F# to G etc. throughout the section. This exercise cleans up coordination of the fingers which is especially important when two or more fingers move.

By Threes

1. Slur by threes making all pitches equal in length.

.jpg)

2. Repeat starting on the second note and slurring by three notes.

3. Repeat starting on the third note and slurring by three notes.

Rhythms

1. Play pitches in the dotted eighth sixteenth note rhythm. (long, short)

2. Play the pitches in the Scottish Snap rhythm. (short, long)

Vibrato

1. Place four staccato Hahs to each beat at quarter note = 50- 60.

2. Slur the staccato Hahs to produce four vibrato cycles to each quarter.

High Note Strategy

On each barline, add a beat and on this beat play a top octave B. This exercise will help you set the embouchure for a higher note and will add ring to the written notes.

Putting It Together

Play through the complete melody. Record yourself. On the playback synchronize the metronome with the recording to discover places where you have rushed or dragged. Note these places in the music. Listen for chipped note beginnings, seamless slurs between the intervals, and rough note endings.

Now the question is whether you duplicate what you have achieved in your practice. The goal is to have played it more times correctly than incorrectly. Your approach to interpretation will continually change as you learn and play more music.