John was an optimist, and he was a firm believer in the power of music and the virtue of the human spirit. He would often become visibly touched by the simplest act of kindness he witnessed. Were he still alive, he would find so much good in what is happening in the band world today. But perhaps more than anything else, he would see the challenges ahead, roll up his sleeves, and say, “Well, let’s get to work.”

In my mind, one of the hallmarks of John Paynter’s contribution to our society was his deep desire to prepare not only the best musician, but also the best person within each student. He truly looked upon his job globally and would not separate the musical and personal aspects of anyone’s development. In the most traditional sense, John, as a teacher, was interested in preparing better citizens to take their place in our society. This strong impulse permeated everything he did.

John’s high musical standards are well known, but this desire to find and instill the best in everyone could be found during his rehearsal lectures to the Northshore Band members, in the expectations (and occasional lectures) he had for his faculty colleagues, and even in his chastisements of the large audiences at the Midwest Clinic. John would often use his famously razor-sharp wit in front of capacity audiences at Midwest Clinic to fill more empty seats, to ask the audience to pay closer attention, or even to exhort them to show more appreciation for what was unfolding before them.

Once in Wisconsin, John was conducting a high school honor band. He noticed that none of the high school directors seemed to be in the rehearsals, but were spending their time in the coffee room. After a couple of rehearsals, he gave the band a break and went outside to join the directors for a smoke. At the end of their visit, and as it was time to resume rehearsal, he turned to his colleagues and asked if they were all ready to return to the rehearsal. This was his gentle reminder that each of them still had more to learn and would be best served observing the rehearsal rather than partaking in another doughnut. Not everyone appreciated John’s consistent and constant efforts in this way. He took his traditional role as a teacher seriously, and those who chose to listen and learn from him were all the better for it.

The first time I encountered John Paynter as a student at Northwestern (I had known him professionally earlier in my career) was as a doctoral student playing bass clarinet in the Northwestern Summer Band. I showed up ready for the first rehearsal. We were all warming up and looking through our respective parts, introducing ourselves to each other, and so on. Suddenly the room became completely quiet. I did not know why until I looked around and saw that John had just entered the room. The respect shown at that moment was palpable. I don’t believe I had ever experienced this before, and it certainly made me sit up and take notice. Not really knowing what to expect, I anticipated a stern and grumpy man would take the podium. What I found, instead, was a person who, from the very start, was friendly and witty, but all business and ready to get to work.

In the summers, this business-like attitude was necessary because the band gave a concert every week for six weeks. Each concert was prepared in three rehearsals. Typically, the summer band played to a sold-out crowd in Pick-Staiger Concert Hall, and the repertoire included a wide variety of difficult music. John built this extraordinary summer series over many years to be among the most successful summer music events in the Chicago area. He believed in bringing music to the community and would bus in large numbers of audience members from retirement homes for each concert.

I learned a great deal about quick concert preparation watching John in this summer atmosphere. Because time was so critical, each rehearsal presented musical choices about what to really dig into and what to leave alone. John had an uncanny knack for knowing what performance issues would take care of themselves with another run-through and what issues needed specific attention. This is a skill that all successful conductors learn over time. I also observed how John would spend more time on specific musical issues that were most important to him early in the season, with the expectation that careful attention early on would pay off with more efficient rehearsal later in the summer as students learned what skills were of the highest priority to him.

Another critical skill John brought to the students in the summer band was that of effective programming. The large audiences that gathered for the concerts each week came because they knew they would enjoy a wide variety of music. I recall one concert for which John programmed Ross Lee Finney’s Summer in Valley City. This is an esoteric work, which is extremely difficult to perform and presents a challenge to the listener. John balanced the Finney piece with a number of works at the opposite end of the spectrum to provide balance for players and the audience. At the concert, he spent a bit of time introducing and explaining the piece, and even said to the audience, “Okay, here comes the piece you’re not going to like.” With his inimitable ability to work an audience, and with careful programming around the piece, it was a huge success. I saw him do this time and time again. Through John’s superb rehearsal techniques, terrific programming, efficient administration of the summer concert series, and ability to communicate with the audience, there was much to be learned by those of us who were involved in the summer program. To be part of this was a real joy.

Like the Summer Band, Symphonic Wind Ensemble rehearsals at Northwestern were productive and efficient. John did not believe in wasting his players’ time. He wanted to emulate the professional music-making experience as best he could. In fact, near the end of his career, he advocated for a new approach to ensemble rehearsals. He wanted to experiment with the idea of more closely mimicking the professional experience by staging rehearsals every day for one week before a given concert. After that week, the students would move on to another project or ensemble for a while, or simply have time off to do other things. This was a far cry from the current practice of rehearsing an ensemble on a regular basis, giving a concert every few weeks. This is just one example of John’s willingness to think outside the box.

In talking with a former student about this book, I indicated that I was attempting to describe a typical rehearsal of the Wind Ensemble. He thought it would be very difficult to put that into words. Indeed, when I think back to those rehearsals, I’m confronted with a variety of emotions. Every rehearsal was charged with lots of energy. This energy, however, was not the result of cheerleading from the podium. Rather, it was a combination of the opportunity to make great music with great musicians and a sense of wanting to please Mr. Paynter. Even the most-experienced and discriminating doctoral students knew that they would be better musicians as a result of their experience in the Symphonic Wind Ensemble. In fact, Northwestern is well known as a superb orchestra training school (among many other things). With this in mind, one might expect the top wind and percussion players to be primarily interested in playing in the orchestra. This was not the case. Everyone acknowledged that there was much to take away from playing under John’s baton.

It would be misguided to imply that Symphonic Wind Ensemble rehearsals were free of tension and stress. Some of the stress resulted from the atmosphere John would create on any given day, but most of it was due to the expectations the students placed on themselves. Peer pressure in the room was palpable, and no one wanted to disappoint either their student colleagues or their conductor.

John never spoke above normal conversational volume in rehearsal. This was, I’m sure, a calculated strategy that forced a very quiet atmosphere and increased the level of intensity. If there was much rumbling around or movement during rehearsal, the players would simply be unable to hear him. This caused a subconscious level of quiet and focus that was both attractive and a bit peculiar. Another effective technique he employed was to begin the music barely before everyone was ready. After he made comments to the group, he did not wait. He started. Again, subconsciously, students caught on to this practice and knew that they had to be ready to go in a very timely manner. There was simply no time to waste. While the rehearsal atmosphere was always business-like, the moods between rehearsals would vary. Some days John would come to rehearsal in a somber mood. The rehearsal, of course, took on this character. Those rehearsals would proceed pleasantly, but with little humor or levity.

More often, rehearsals were interjected with humor and John’s notorious wit. One of his most enduring qualities was his ability to use that wit to correct and even chastise his players. He had a very unique way of making the person he was addressing feel good about himself or herself, often with a chuckle, while at the same time making a significant musical point regarding that person’s playing of a certain passage. This was done without sarcasm, which can be negative. It was often subtle, but never went over the heads of the bright students who attend Northwestern. At the risk of sounding smug, I believe this manner of interaction was highly effective at NU, and it was a skill John honed over a long career at this single institution. I consider this to be yet another example of how John and Northwestern were so closely intertwined and how, in some ways, the University molded the man.

In the rehearsal process, John was direct. He believed he owed it to his students to be nothing less. They were there to learn and improve—to become the best musicians they could—and his job was to help them achieve that goal individually and collectively. He was always teaching. The reason John could be so direct was that he left no doubt that he knew his stuff. There was no waffling about anything he did in rehearsal. As soon as a problem occurred, or he wanted to offer some individual musical (or personal) advice, he would stop and get directly to the issue. Again, this was most often done pleasantly and with a touch of humor, but still directly. I don’t recall any time when he stopped and hesitated about what to say, or whom to address. He would stop, describe the problem, offer a solution, and move on.

Sometimes it was difficult to predict how the work on a piece would progress. Occasionally, he would work very hard to make a particular point. He could, without hesitation, stay on ten measures for thirty minutes. This did not happen often, but he would use the situation to perfect a particular style or to make the point that he expected a great deal from his players. Conversely, there were many times when I would think another run-through of a certain section of music would be helpful, but he would leave that last run-through for the performance. This was not uncommon and added to the excitement of the concert itself. He trusted that it would be great at the performance next time—and this was perfectly acceptable with players as good as those with whom he worked.

While John’s rehearsals were business-like, there was time for a story here and there along the way. The apologues were part of John’s style, but they were always offered with a particular purpose. He had a great knack for sharing a tale and then very neatly wrapping it up into a package completely relevant to the point he was trying to make. Unlike many band conductors later in their careers, he did not wax on in rehearsal without a specific purpose to the story. He was nothing if not efficient and respectful of his students’ time.

John was direct with his criticism, but it was not offered in a mean or personal way; it was always simply matter of fact. The reason for critical suggestion was to improve the music and improve the performer. It was that simple. Most students learned that John did not pick on people. He just wanted to make them better. The exception to that would be if a particular student was consistently unprepared or overtly demonstrated a lack of respect for what was going on in the room. Should he detect that, John’s sharp tongue and quick wit could immediately lay someone out.

Positive feedback was also very much a part of the process. Such feedback would not be effusive. It would be rendered quickly and honestly. It might be as simple as, “Have you ever heard anything more beautiful?” Such comments came often and, most importantly, were heartfelt, so they meant a great deal to those to whom they were directed.

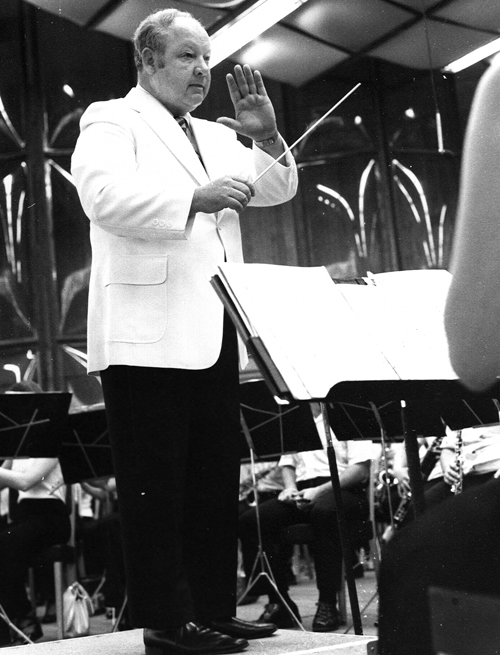

John’s particular conducting style was not expansive. His gesture was clear, but never over-done. His focus was truly on the music and the way it sounded.

Occasionally, on a lighter day, students might attempt to engage in a bit of banter with John. This was always humorous because they would soon be drawn and quartered by his remarkably quick wit. In my opinion, he had no equal when it came to his amazingly quick mind (except maybe Marietta). And best of all was when someone became a victim to his wit and didn’t even know it. I count myself among the many folks, including students, deans, faculty colleagues, and conducting colleagues around the country, who dared to challenge, but learned the hard way, that he always won.

John’s effectiveness on the podium was a result of several important factors: his superb musicianship, his extraordinary ear, and his thorough preparation before each and every rehearsal. His musicianship was enhanced by his consistent desire to improve, and stay aware. He and Marietta were regular attendees at the Chicago Symphony. He listened to music constantly and was always expanding his musical palette. John found great value in listening to music outside of the wind band world. He knew that a wide variety in his musical diet was essential to his own growth. He was proud of his colleagues at Northwestern and loved to rub elbows with them. He claimed to learn from them every day. Being associated with the finest musicians, both colleagues and students, for more than forty years clearly had a positive effect on John Paynter the musician—yet another example of his inseparable relationship with Northwestern.

John’s degrees in theory and composition presented an unusual pedigree for a band conductor. He considered himself very much to be a theorist and an arranger. Indeed, his output was very large. His theoretical knowledge gave John a unique perspective as a conductor. While all conductors bring a grasp of music theory, John’s degrees in theory afforded him a large advantage when trying to understand the music he was conducting. His background was also helpful in preparing his remarkable ear. He could hear and discern exactly what was unfolding within any musical setting to a level I have rarely encountered.

John did not rely on his musical skills alone in rehearsal. His confidence was acquired through hard work. His most basic premise, resulting from the influence of his father and Mr. Bainum, was to simply work harder than everyone else. He spent endless hours at his desk studying scores. I remember looking in on him at one point before rehearsal. He was poring over his well-worn score of the Hindemith Symphony. I asked what he could possibly be studying after having performed the work so many times. He replied, with that well-known twinkle in his eye, that he learned something new every time he opened that score. John never stopped studying, learning, and working.

One of John’s more infamous habits was to program long—often very long—concerts. He simply loved the music too much to let any of it go. Additionally, he conceived each concert as a composition itself. Each piece played off the others, and the whole event was to be taken as an organic experience rather than simply as a group of works thrown together. This often made for very long evenings at both Northwestern and Northshore Band concerts. I remember a Symphonic Wind Ensemble concert in the winter of 1990 that started at 7:30 p.m. At 10:00 p.m., John cut the concert short, announcing that everyone had heard enough for one night and the audience could come back next time to hear the last piece.