One of the great pleasures of my job is the chance to meet so many interesting musicians. A century ago, differences in technology and transportation made it nearly impossible to meet a composer in person. If a conductor wanted to ask Gustav Holst a question about one of his compositions, there was little hope other than to send him a letter. Now, if you want to talk with David Holsinger (interviewed starting on page 14), you can just walk up to him at the Midwest Clinic. With the availability of computers and videoconferences, it is even possible to have a composer work with your ensemble from thousands of miles away.

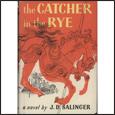

I have been thinking about elusive artists in the wake of J.D. Salinger’s death on January 27. For decades Salinger has been one of America’s most reclusive famous people. Generations of high school students have read The Catcher in the Rye, and many have loved its story of a troubled, rebellious teenage boy and his adventures in New York City. The book is also loaded with gobs of symbolism, enough to keep high school English teachers busy for weeks. (I could send you a copy of one of my old term papers if you need help understanding the imagery). The book still sells about 250,000 copies annually.

For much of its life in print, copies of Catcher have contained neither a biography nor a photo of its author. Indeed, when the author died, many newspapers printed the same ancient file photo, depicting a young man with dark hair. At a period of great fame in the early 1960s, one of the most popular authors of the 20th century walked away from the spotlight.

The reasons for this departure have always been murky. Some have speculated that the overwhelming crush of fame and ad-mirers was a significant factor. In many ways this explanation is a bit surprising. Critics have noted just how much Salinger pined for success in his early years as a writer. With the publication of his novel in 1951, his days as a rising New York star came to an end. When fame arrived, it was a wave far bigger than Salinger could have imagined. He moved in 1953 to a 90-acre compound in Cornish, New Hampshire and lived there until his death.

Although life in Cornish was undoubtedly slower than in New York. Salinger still socialized a bit after the move. Much of his fiction involved young children and their concerns. He reportedly invited local high students up to his house to talk and listen to records. In one famous incident he even consented to an interview with a local student. The interview was originally intended for the high school page of the local paper, but overeager editors, mindful of the scoop they had, gave the interview a prominent place in the newspaper. Salinger promptly stopped inviting students to visit.

As Salinger’s isolation from the outside world grew, the publication of his work slowed considerably. Having previously released an acclaimed collection of his stories from The New Yorker (Nine Stories in 1953), Salinger published two additional books based on novellas that were also printed in the magazine. Compared with the earlier short stories, the later works were longer, weirder, and more rambling.

His final published work, a 25,000-word story called Hapworth 16, 1924, appeared in The New Yorker in June 1965. For many people the only way to see this bizarre final statement was to read a copy of the original magazine. As a high school student, I spent a long Saturday afternoon pouring over the story at the public library. The engaging prose of Catcher was gone. Salinger, hero to many, seemed to push his audience away with his later work.

In the years that followed, Salinger shunned nearly all requests for interviews, and the people of Cornish fiercely guarded his privacy. Salinger did give one tantalizing glimpse of his life in seclusion when he told the New York Times in 1974, “Publishing is a terrible invasion of my own privacy. I like to write. I love to write. But I write just for myself and my own pleasure.” With these words, Salinger held out hope that someday there might be new works to read.

Those hopes rose a bit when articles on his death included a decade-old comment by a neighbor that Salinger had at least 15 unpublished books kept in a locked safe at home. The possibilities were breathtaking. His literary representatives were silent on the prospect of new books. There is always the possibility that the books are just as dense and dull as some of his later published work. Still, the prospect that the author of Catcher might have more to share with the world is undeniably exciting. I’ve been waiting 25 years to find out what Salinger has been keeping.