American composer Katherine Hoover is well known for her two solo flute pieces Kokopeli, Op. 43 (1990) and Winter Spirits, Op. 51 (1997). Hoover was inspired by the Native American land, culture, and more specifically, by the Hopi tribe after trips to the Southwest. Players will understand these two compositions better when they learn about the music, religion, and holy beings within the Hopi culture.

Located in northeastern Arizona, the Hopi are one of many indigenous tribes in that area. They call themselves the “Peaceful People” (Hopituh-shinumu) and claim to be the oldest inhabitants of North America.1 Although each of the eleven Hopi villages has its own unique characteristics, they share a common thread – a way of life that derives from their creation and migration stories.

Creation

The Hopi believe that the Creator (Taiowa) made the heavens, holy beings (kachinas), nature, and mankind. When the people obeyed the Creator’s plan, people lived in harmony alongside the kachinas. To the Hopi, a kachina is a supernatural being who normally brings rain, crops, and health to the tribe. Although seen as a living entity, the Hopi do not view these spirits as gods, but as guardian angels. To restore peace, the Hopi hold kachina ceremonies throughout their calendar year, although most take place during the winter solstice; coincidentally, parallels can be drawn between Winter Spirits and the solstice, although it was not Hoover’s original intention.

Migration

When the people were disobedient, they were exiled from the land and told to dwell elsewhere. Upon their emergence into the new world, the Hopi divided into clans and began their migration with the help of insect-like beings (máhus). The máhus endured hardships so that the people could inhabit the land, and playing flutes was a way to diminish their pain.

During the migration, the Hopi people carved images in the rocks of the máhus playing their flutes. Some scholars claim that these images are of Kokopeli, the famous humpbacked-flute player, although others disagree. The máhus also sang songs, some of which are so ancient that many present-day Hopi no longer know them.

Hopi music is woven into their lives, and serves three functions: sacred, social, and personal. Because of this, the Hopi are also called a “People of Song.”2 They use songs, dances, and music in their sacred ceremonies, and the musical activities have great significance to them. Non-tribal members rarely hear these songs.

For social events music is used as part of work, such as with corn grinding songs. While the women prepare the corn, music keeps them entertained. Lullabies, love songs, and meditative music fall into the third category of personal use. Hopi music is considered to be “the most complex music of all the North American Indian tribes.”3

The Hopi Flute

The flute brings life to Hopi music and is believed to have supernatural powers. It is an ancient instrument and originated with the Hopi migration stories. Unlike the modern transverse flute, a Hopi flute is held vertically, similar to a recorder, and the player blows into the top end of the instrument. The tone holes are along the side of the tube, which is made out of bone, wood, or reed. A painted gourd cup is attached to the end of the instrument for amplification.

Katherine Hoover’s Music

Kokopeli, Op. 43 and Winter Spirits, Op. 51 are both for solo flute and categorized as programmatic music. Hoover musically notated her thoughts and interpretations of Native American music for these two pieces, and tried to capture the limitless sounds and space of the Southwest. In an interview with Elaina Rigg, Hoover stated, “as for [a] theoretical analysis…I have never given [Kokopeli] a moment’s thought in this direction.”4 It is safe to say that this holds true for Winter Spirits, as well. The intention is for the performer to make these two pieces their own, as is obvious from Hoover’s statement, “there are many aspects I prefer to have left free.”5

Kokopeli, Op. 43 (1990)

Kokopeli is a through-composed work without repetitions of any major sections; each verse has its own unique melody.6 As you play or listen to it, you can hear the Native American sounds quite distinctly. This is due to the structural and melodic form, lack of key signature, key, and rhythm. Meter and barlines are nonexistent. Therefore, when referring to musical examples I will use line numbers for each stave.

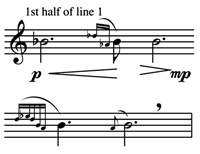

The absence of barlines indicates that time should not be taken literally. This will help you capture the “great spaces and sky,” within the piece.7

Notice the breath mark in the example above. It is another device incorporated to create the feeling of space. Although a breath mark can serve its traditional function, it also suggests a pause before continuing with the next phrase. This is also consistent with Native American musical style. The Hopi are known to incorporate mysterious pauses within their songs.8

Key signatures, like barlines, are not used in Kokopeli. Hoover states that “Accidentals carry through the line, but do not carry over the octave.” Traditional Hopi music also does not include these elements, although their music suggests that they were familiar with the concepts on an intuitive level.9 However, even without a formal key signature, it is easy to conclude that Bb is the work’s tonal center. It is not only the first and last note of the first phrase, but it appears seven more times in the piece as a long sustained note.

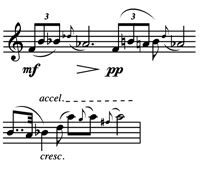

Contrasting tempo and dynamic markings are evident throughout Kokopeli, and they are often found within close proximity of each other.

As indicated by the composer, tempo markings are approximate. However, I suggest following the given tempo indications at first, just until you feel comfortable with the piece. Because Native American music is traditionally improvisational, that approach works well with Kokopeli in terms of tempo and rhythm when you are ready to loosen it up.

The rhythms in this piece are similar to those of the Hopi music.10 Note values range from whole notes to grace notes within a single line.

Native American music often imitates the natural surroundings, incorporating the sounds of nature, such as bird or insect chirps. The grace notes here are a stylistic feature that functions in that way.

Winter Spirits, Op. 51 (1997)

Like Kokopeli, Winter Spirits is based on Native American sounds. Musical element such as the structural and melodic form, lack of key signature, and rhythm, create this effect. There are many similarities between the two pieces, but there are some differences as well.

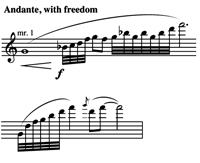

Winter Spirits uses barlines and has “definite sections which contrast with each other.”11 These contrasting sections are found on a small and large scale within the piece. For instance, the beginning starts with a long slurred phrase indicated to be played with freedom.

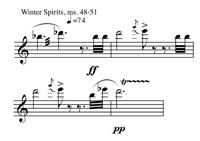

However, at the end of the piece, the mood changes drastically when articulated 32nd notes and accented eight notes are found within shorter bar lengths.

The fact that Hopi melodies are nearly impossible to dictate in the Western notation system led researchers to conclude that the Hopi “conceive melodies as series of contours rather than a series of discrete pitches.”12 For example, the note range is rather wide, the lowest being Db4 and the highest being B6. So when playing Winter Spirits, try to think in contours rather than individual notes.

Understanding the cultural traditions and history of the Hopi that Katherine Hoover incorporated into her music, will help you give a better performance of these works.

References:

1Frank Waters, Book of the Hopi: The First Revelation of the Hopi’s Historical and Religious World-View of Life (New York: Ballantine Books, Inc. 1963), xv.

2Harry C. James, The Hopi Indians: Their History and Their Culture (Idaho: The Caxton Printers, Ltd., 1956), 174.

3James, 181.

4Hoover, unpublished interview by Elaina Rigg, January 26, 1999. E-mail attachment from Hoover to author.

5Ibid.

6Virginia Tech Multimedia Music Dictionary, “Through-composed” http:

//www.music.vt.edu/musicdictionary/ (accessed March 18, 2009).

7Hoover interview, January 26, 1999, Interview by Elaina Rigg.

8Renita Freeman Ashmore, “The Native American Flute” (Master’s thesis, California State University, 2000).

9Paul Collaer, Music of the Americas: An Illustrated Music Ethnology of the Eskimo and American Indian Peoples (New York: Praeger Publishers, 1973), 34.

10Bruno Nettl, Music in Primitive Culture (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1956), 112.

11Hoover interview by author, January 12, 2009.

12George List, “Hopi Melodic Concepts,” Journal of the American Musicological Society 38, no. 1 (Spring, 1985): 144.