Over the past 20 years extended techniques have become a fundamental skill for aspiring and established professional flutists. College students cannot escape studying at least one piece with extended techniques, and professional flutists encounter them on a regular basis. Despite their prevalence, contemporary techniques are largely ignored by teachers of young students. They address them when students ask but often fail to explain how they also apply to traditional flute playing. Teachers of all levels should incorporate these techniques into their curriculum.

Pedagogical Benefits

Contemporary techniques can improve the primary fundamentals for good tone production. Many materials are available to help teachers use extended techniques as pedagogical tools (see appendix). Students will appreciate the quick progress that results from using these techniques.

They also break up the tedious routine that often occurs when working with beginning students. Many beginners grow frustrated when progress is slow. When students explore and experiment with something fun like throat tuning (singing and playing or vocalizing) or harmonics, they see the expanded possibilities of the instrument.

Finally, familiarity with extended techniques at a young age is tremendously beneficial for flutists who will pursue music as a career. Students who only learn traditional repertoire are more likely to reject extended techniques when they encounter them later. Teachers should work to create well-rounded musicians through exposure to various types of music, even for those students who may not choose a career in music.

Tone Development

Harmonics, throat tuning, and whistle tones help develop the embouchure and create a focused, resonant sound. They can be introduced to beginning and intermediate students, either as part of the regular curriculum or as particular fundamental problems arise. For example, harmonics develop lip strength and focus in the low-mid registers. Various exercises, regardless of their perceived level, can be useful in solving students’ problems.

Harmonics

There are many harmonic exercises that are easy to learn and memorize. As Robert Dick explains in Tone Development through Extended Techniques, harmonics occur “when low octave regular fingerings are overblown through their overtone series. The flute produces pitches in the overtone series for pipes open at both ends, called natural harmonics.”1

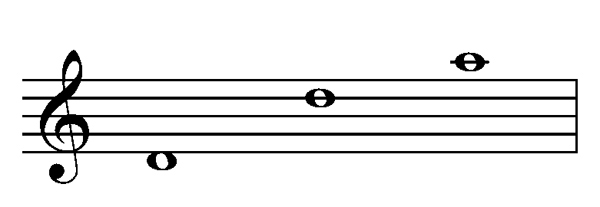

Here is the harmonic series when C is the fundamental (or first partial):

His book also includes exercises that extend from the most basic to alternating between harmonics and regular fingerings. The basic harmonic exercise, #1, in Dick’s book is a good place to start with young students.

Young students should also try Patricia George’s harmonic exercise. It starts on low D as the first fundamental and overblows to the octave (the first partial) and the fifth (the second partial). The fundamental notes ascend chromatically to middle C#. “See, Sue, Pooh” are words that accompany the exercise to guide the shape of the lips.2 These words naturally open the oral cavity to produce the embouchure shape and air speed necessary.

Whether you create your own exercises or use the ones here, the ultimate goal for practicing harmonics is to find and develop an awareness of the best embouchure position for each note.3

Vocalization

Because most extended techniques enhance tone production and embouch ure awareness, a second technique to incorporate for tone, resonance, and tone color is singing while playing (throat tuning or vocalizing). Throat tuning can only be mastered by simultaneously singing and playing, but the benefits are tremendous.

Robert Dick includes an excellent explanation of the benefits of vocalizing. He says that flute sound comes not only from the flute but also from the player, and because each body is different, players’ sounds differ. His analogy of comparing a vibraphone’s resonating tube to the throat provides a visual image of what vocal chords can do. “To understand this sensation, play a note on the piano or other fixed-pitch instrument that is comfortably in your vocal range. Then, prepare to sing it. Before the note is sung, there is a change in the throat when the vocal chords are brought to the correct position to sing the pitch. When the vocal chords are held in position to sing a given pitch, the throat is in position to resonate that pitch best.”4

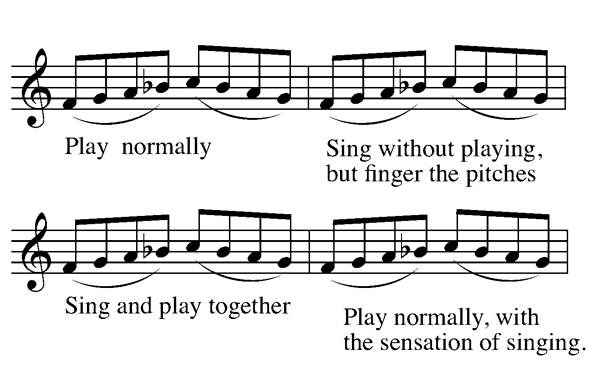

It takes time to develop the skill of singing while playing, but once players are aware of their vocal chords, the following exercise is excellent. It is identical to Exercise No. 1 in Taffanel and Gaubert’s 17 Big Daily Exercises.  Play the five-finger pattern normally at first, then sing it without playing while fingering the pitches, then sing and play together, and finally play normally but with the sensation of singing.5

Play the five-finger pattern normally at first, then sing it without playing while fingering the pitches, then sing and play together, and finally play normally but with the sensation of singing.5

Students should choose a starting pitch for the exercise that fits most comfortably within their vocal range. As they become more comfortable with it, they can expand their range. When traditional teaching fails to help students produce a resonant sound, vocalizing while playing generally produces positive results.

Whistle Tones

Whistle tones, sometimes called “whisper” tones, help relax the embouchure. Although difficult to produce initially, whistle tones produce an immediate effect and create a freer, more resonant sound; lip flexibility is increased, and the lips naturallymove forward, creating more space between the front teeth and lips. As William Kincaid said, “This little calisthenic makes an excellent warm-up exercise for embouchure placement and breath control. It is an excellent discipline to try to isolate one note from the whistle series and sustain it for 10 seconds. The slightest change in breath support will flick you to one of the adjoining whistle notes.”6

Whistle tones are produced by gently blowing a very slow air stream across the edge of the embouchure hole. As Dick points out, players should experiment with tongue position when practicing whistle tones. “When the tongue is positioned correctly, the loudness of whisper tones can be greatly increased, although they always will be a relatively soft sonority.”7

Whistle tones can be a challenge for young players, because they require great tongue and lip control. First ask students just to whistle without the flute. Then have them maintain that whistling position as they add the flute and blow a slow, steady stream of air. The high register is usually the easiest and least frustrating. Help younger students finger the proper pitches if experimenting in a lesson.

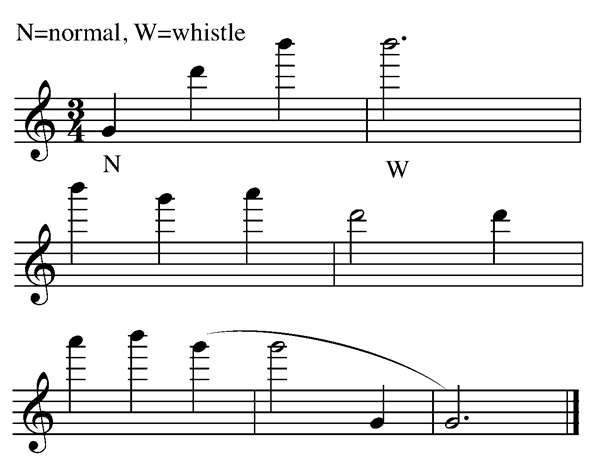

Once they can produce a few whistle tones, many exercises can be used. The best that I have found is in Peter Lukas-Graf’s Check-Up, which has an exercise that combines normally-played pitches and whistle tones. Not only is this more challenging (and interesting), but it immediately improves the quality of the normally-played notes.

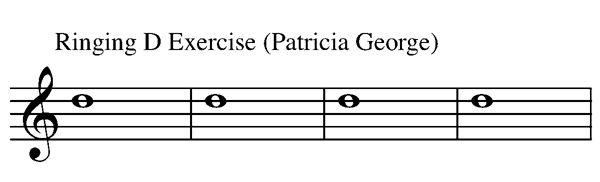

There is a practical approach to daily extended technique practice that can be incorporated into traditional practice to expedite progress. The practice chart on the previous page is for intermediate to advanced students that shows a standard daily warm-up that includes all these techniques. Also included are Marcel Moyse’s long tone exercises from De la Sonorite and Patricia George’s Ringing D’s exercise, both of which are good for finding the sweet spot in your tone.

Even traditional, early 20th-century flute repertoire includes some of these techniques, such as the harmonics found in Debussy’s Syrinx and the flutter tonguing in Darius Milhaud’s Sonatine. Information about these techniques was scarce for a long time. Today there are many resources available to help advanced students develop their contemporary skills. Educational material for beginning to intermediate flutists, on the other hand, remain scanty.

Reworking advanced material, such as that in Tone Development through Extended Techniques, for young players is a nice solution. In addition, many of Dick’s pieces, such as Lookout, have accompanying lesson tapes with tips and guidelines. Lesson time can be devoted to teacher-composed exercises for young students or to the extended technique series of books by Linda Holland, Easing into Extended Techniques. For additional teaching ideas, the best resource is Dean Stallard’s website (www.fullpitcher.co.uk/Dean.htm). Also, Phyllis Louke has composed a set of short duets, Extended Techniques: Double the Fun, in which students can actually use extended techniques musically without being over challenged or intimidated. These duets also work well with a flute choir.

Using extended techniques as teaching tools is an important and exciting progression for serious teachers. Their effects on audiences can be tremendous, and students gain an understanding of contemporary music – a beneficial preparation for successful college auditions. It is our responsibility to provide them with that understanding.

Extended Techniques Resources and Repertoire

For Beginners:

Richard Rodney Bennett. Six Tunes for the Instruction of Singing Birds (Novello)

Linda Holland. Easing into Extended Techniques, Volumes 1-5 (Con Brio Music Publishing)

Phyllis Avidan Louke. Extended Techniques—Double the Fun (Alry Publications)

Dean Stallard. First Journey to the Beyond (Norsk Noteservice)

For Intermediate:

Joseph Diermaier. Five Images after paintings by Arnold Schöenberg (Universal Edition)

Robert Dick. Lookout (Multiple Breath Music Company)

Robert Dick. Flying Lessons, Volumes I-II (Multiple Breath Music Company)

Kazuo Fukushima. Requiem (Suivi Zerboni)

Linda Holland. Easing into Extended Techniques, Volumes 1-5 (Con Brio Music Publishing)

Advanced to Professional:

Robert Aitken. Plainsong (Universal)

Luciano Berio. Sequenza I (Zerboni/Universal)

Elliot Carter. Scrivo in vento (Hendon Music)

Robert Dick. Tone Development Through Extended Techniques (Multiple Breath Music Company)

Toru Takemitsu. Voice (Salabert)

*for a more exhaustive graded list: http://www.helenbledsoe.com/erep.html

1 Dick, Robert. Tone Development through Extended Techniques. St. Louis: Multiple Breath Music Company, 1986.

2 George, Patricia. Flute Spa. No Publisher.

3 Meador, Rebecca Rae. “A History of Extended Flute Techniques and an Examination of their Potential as a Teaching Tool.” DMA thesis, University of Cincinnati, 2001.

4 Dick, 9.

5 Ibid.

6 Krell, John. Kincaidiana: A Flute Player’s Notebook. Culver City: Trio Associates, 1973.

7 Dick, 26.