Gary Smith has spent a lifetime in music beginning in childhood at the Smith Baton Camp, founded by his parents in 1949. The camp, which would evolve into the Smith Walbridge Clinics, was the first of its kind. From a young age, Smith met such distinguished collegiate directors as Harry Begian, John Paynter, Nilo Hovey, and Charles Henzie. Smith later decided to pursue a career in music education and earned degrees from Butler University and Ball State University. He taught first at North Side High School in Fort Wayne and moved later to college positions at Saint Joseph’s College and Indiana State University. In 1976 he joined the faculty at the University of Illinois as Associate Director of Bands and Director of the Marching Illini, a position he held until 1998. He also ran the Smith Walbridge Clinics from 1983 to 2013. Although to some he is best known for his work in the marching field, Smith also has strong ideas on directing concert bands, one of his true passions. Among many career honors, he was elected to the American Bandmasters Association in 1988 and is currently the president elect.

How long have you been a part of the Smith Walbridge Clinics?

I did maintenance work and cleaned cabins until high school. Then I took over the clinic store and canteen. In college I started teaching, especially drum major camps. In 1983 I took over the operations in Syracuse, Indiana until we sold the camp grounds.

How did the philosophy and curriculum of the camp evolve throughout the years?

It started with my dad. The original intent of camp was to train drum majors. We taught them how to do drill, how to write charts, and how to conduct. Back then, drum majors ran the marching band and did all the teaching because few directors knew much about marching. The philosophy at the beginning was to provide a resource for learning about marching band because it was not being taught in colleges.

I developed the motto, “system plus spirit equals success,” from Charles Henzie, my college band director. I saw how to sum up a great band with this little theory, and built my career around it. When I started teaching, almost all marching bands were run through fear and stress. It bothered me. When I took over the camp, I did an immediate 180-degree change. Some instructors resisted the change but they quickly realized that students learned more quickly and found joy in working hard.

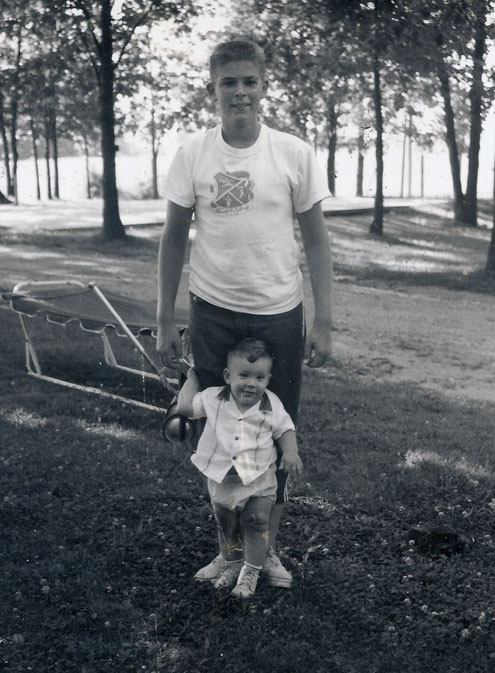

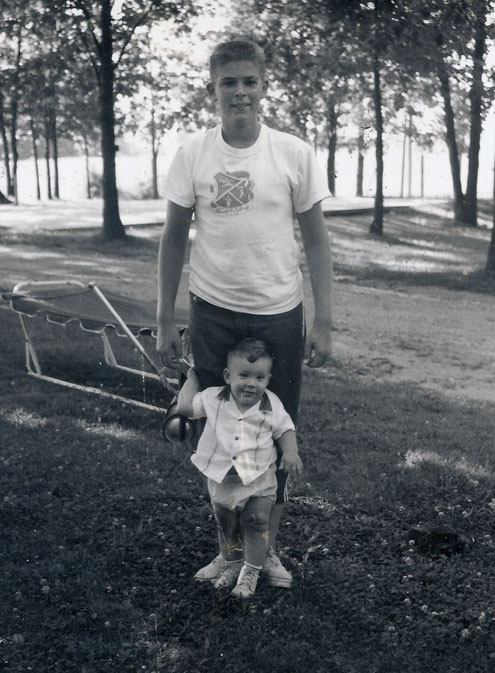

Gary with brother Greg, 1961.

How did you fare in your first college job at St. Joseph’s College?

They had previously eliminated the marching band after a performance that was so bad that people brought vegetables to throw at them during the show. I was expecting 100 students to turn out for band, but at the first rehearsal, only 18 showed up. I worked hard to get them excited, and we had 45 – a wind ensemble-sized group within a couple weeks. One day I took everybody outside during class for some exercise and sunlight. I lined them up in a company front, and taught them how to march down the field with a comfortably sized step. As we did this, about 40 college kids sat on the sides watching, clapping, and yelling.

That night I went home and wrote a four-part arrangement of Man of La Mancha, which was popular then. We played through it in the band room and then we went down to try it on the field. As we were marching up and down the field, about a hundred college kids were there cheering. Suddenly, the band was excited, and they said “let’s do it at a football game.” Even though the season was half over, we showed up to play at a game and the crowd went crazy. It took off from there. We were up to 90 players when I left.

What did you learn from teaching with George Graesch at Indiana State?

He had a symphonic band of about 90 players, and I had a tiny second band about 35 players. The Indiana State marching band was really good, and I learned a lot about entertainment by watching their films. I felt he was the best college band director in the country then.

My first love was concert band, and it was frustrating not to be able to play good literature with such a small second band. George was an anti-wind ensemble guy and believed in a full symphonic band; his philosophy was similar to Harry Begian’s, who I worked with later at the University of Illinois. To show how unselfish Graesch was, he cut his top band down to a wind ensemble with 43 players, and all of a sudden I had a 90-piece symphonic band. It was a good band, and it really excited me.

Then as the marching band became even more popular, our numbers took off and I started a third band. I directed the second and the third band because I realized that the better I made the third band, the better the first two bands would be. These groups really became good by my third or fourth year.

Why did you use flugelhorns to cover third trumpet parts in marching band?

That is a concept I still believe in, and I almost hated to see it go away. When trumpets have notes at the bottom of or below the staff and try to play loudly, they get a raspy, edgy, bad sound. The flugelhorn has a larger bore and can produce more volume in that part of the range.

Flugelhorn also adds a different color to the ensemble that can be used a variety of ways. For example, if I wanted the music to sound like there were four trombone parts, I might use two trombone parts, baritone, and flugelhorn. Flugelhorn can also strengthen a mellophone part. At times, I even used flugelhorns as a separate section.

Using flugelhorns fattened the sound of the band. My marching bands had a lot of middle, which is not something frequently encountered. It also gave a bit more prestige to playing third trumpet parts. I even had some music majors request being placed in that section because they did not want to mess their chops up playing high all the time. There were a lot of advantages to using flugelhorns.

How did you make your college basketball bands such a success?

When I taught at Indiana State, we were one of the first to use a rock band within the band itself, so the basketball band was extremely popular. Incidentally, Larry Bird was red-shirted at Indiana State during my last year there. The band was popular because we played current music: Blood, Sweat, and Tears; Chicago; and Earth Wind, and Fire. When I came to Illinois, I added the rock band, which meant we played a lot more between plays. Some people thought it was a distraction, but the coach liked it.

When you moved to the University of Illinois, how did you make the second band so successful?

I never called my group a second band. There are just good and bad bands. I don’t think the kids who were in it ever viewed themselves as a second band. When I got on the podium and worked with the symphonic band, it felt like waking up on Christmas morning. Every rehearsal I ever went to, I experienced that enjoyment. I’d look forward to it that much – especially the fact that I had full instrumentation and talented players. I could perform just about any kind of work I wanted. I had no desire to become director of bands anywhere, because my band at Illinois was so good. I had no interest in going to another school just to have the director of bands title.

When you are a successful marching band director, people tend to stereotype you and are unaware of other things you do. I think most people who direct marching bands use it as a stepping stone to break into a director of bands job. It is more rare that someone makes their entire career in college marching band.

To the general public the marching band director is considered the leader of the program. The average football fan has little idea that other bands even exist. In the profession the most prestigious position is director of bands, and the assistants are sort of looked down on because they do not to get the same level of invitations to guest conduct.

Did you approach your ensemble any differently than you would any other ensemble?

I have worked with middle school and high school bands, and I have found you are better off not to lower your standards or talk down to any group. Good pitch is good pitch; good intonation is good intonation. The only difference would be the areas I could focus on in rehearsals. In some pieces when the pitch and tone was good, I could talk about style and articulations. When it wasn’t, I talked about breathing, tone, and pitch. When I get a on podium, the first thing I do is establish a concept of ensemble sound, even when I’m guest conducting. I have devised techniques and methods to achieve that quickly because in many cases I may only have one day to work with a group, and I do not want to just start working on the music itself. Unless you fix the things that cause music to sound good, it is never going to sound good.

How do you prepare for rehearsals?

I learned in college to set short- and long-range goals. I would write down my goals for the day, week, month, season, and the next five years. I approach marching band the same way. For each rehearsal there was a lesson plan, often written right up on the board or passed out to section leaders. The players appreciated seeing our progress toward our goals each day.

What is your approach to programming literature?

When I was in college, we played mostly original band works. I was never a fan of transcriptions until I heard Begian’s group play. He spent time mentoring me on the proper way to perform transcriptions, which opened another whole realm of great literature. Although I believe that 90% of transcriptions do not work for band, there are the 10% that are great. I have always been attracted to new contemporary works, at least ones with enduring value, rather than works that sound like some guy beating his fist on the piano. There is a difference between temporary music and contemporary music.

Having grown up in the camp world, I had heard every march ever written by the time I reached college. I can get on the podium and conduct almost any march by memory. Diversity of literature is something lacking in many modern school band programs, with an overemphasis on new works.

What is your approach to score study?

A long time ago I read an article with some of the great maestros on the role of the conductor. I think Solti said that the role of the conductor is to compare what the ensemble is playing to what is in your head, and try to match them up. If you don’t have anything in your head, you are just beating on notes and rhythms.

With score study and listening to every performance I can find, I try to get an overall view of how it sounds. I am not so brilliant that I can look at a score and know exactly how it will sound. I use George Solti’s method of marking scores with colors. He uses highlighters, a certain color each for primary lines, secondary lines, and important cues. I mark when there is a tempo or meter change, because this allows you to glance at the score and see what is coming. However, I do not mark the score until I have studied it a lot, because this can lead to many unnecessary marks. I mark the critically important things, such as a cymbal crash or the introduction to a solo.

I sing complex parts, which I also do later when students have difficulty in rehearsal. I learned that from Begian. who almost always sang how he wanted something played, whether it was a rhythm or shaping a line. If I am conducting a tune I know well, like the Holst Suites, I know instantly if someone’s playing a wrong note and who it is, because the music is in my head.

What are the most important lessons you learned from Harry Begian?

I went to him because I revered him, I thought he was the greatest band conductor of all times. I do not think there’s ever been anybody better. Revelli was good, too, but I felt Begian was a notch better. I would sit there and quiz him on interpretation of marches, warm up, tuning, listening, and solfege.I wanted to glean everything I could from him.