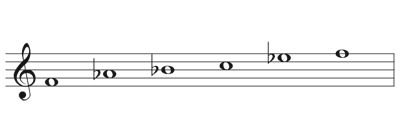

The most common form of the blues, the 12-bar blues, is a cyclical (repeating) musical form, usually in a 4/4 time signature. Most of the original blues melodies were based on the minor pentatonic scale. This scale is an important resource for improvising.

The minor pentatonic uses what we refer to as blue notes, specifically the minor 3rd and the minor 7th. These blue notes, or more specifically, the harmonic tensions they create, are what characterize the sound of the blues. One additional blue note is the diminished 5th. Although absent from the minor pentatonic, it is equally important in playing the blues.

Form

Understanding the form of a tune is an important first step in improvisation, and one that is often overlooked by beginners. This may explain why one of the challenges facing a novice jazz player is how to keep one’s place in a tune while improvising, without the melody indicating the form. Simply put, if musicians are not aware of the form, it is easy to get lost. The solution is also simple. To play by ear jazz musicians should first train themselves to rhythmically feel the built-in phrases within a tune.

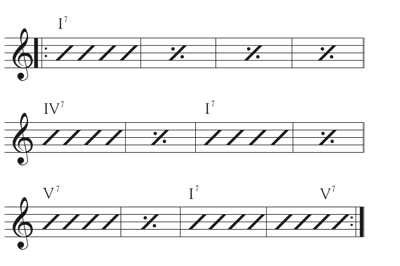

With the 12-bar blues, this is relatively easy. Think of it in three 4-bar sections. Then, taking a cue from the early blues singers, break down each 4-bar section into two 2-bar sections. Most of the original blues songs consisted of a 2-bar melody (roughly 2 bars), which kicked off each 4-bar section. Using the call and response technique, a tradition prevalent in many aspects of the African culture, the vocalist sings a 2-bar phrase based on the minor pentatonic (call), which is followed by a vocal or instrumental 2-bar fill (response). This call and response pattern shaped each 4-bar phrase within the 12-bar blues. With this in mind, listen to several blues songs and observe how the melody loosely resembles an AAB form: the theme is stated in the first 4 bars, repeated in the second 4 bar phrase (AA), and followed by a variation of the theme in the final 4 bars (B). Melodically, this outlines the basic 12-bar blues form. (see below)

Develop the ability to feel the length of the 4-bar phrase by listening for the 2-bar call and 2-bar response pattern. It is built right into the blues form. Once musicians begin to feel the length of each phrase, they can take the next step and hear the changes or chord progression.

AAB 12-Bar Blues Form

Chord Progression

The basic blues chord progression consists of three dominant 7th chords, built on the first, fourth and fifth degrees of the tonic scale of the tune. The dominant 7th chord is a major triad with a minor 7th. (I7-IV7-V7). For example, in a blues in F, the chords are F7 – Bb7 – C7.

Next, examine the AAB blues form of the melody in relationship to the harmony. The first four bars are on F7 (I7 chord). In the second 4-bar phrase, the melody (and lyric) is repeated, although the Bb7 (IV7 chord) now provides some harmonic tension for two measures. In the third 4-bar section, both the melody and the lyric are different, and played (or sung) over C7 (V7), adding even more harmonic tension, before it resolves back to F7, the tonic key. The C7 in the last half of bar 12 is called a turnaround, harmonically setting up the return to the beginning (top) of the tune. Hearing the changes becomes easier with practice.

The Blues Scale

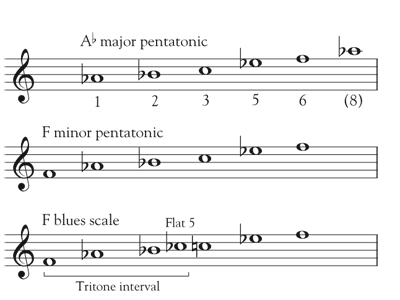

The blues scale is derived from the minor pentatonic scale, and the minor pentatonic from the major pentatonic. Just as every major key has a relative minor, so it is with the pentatonic scale: any relative minor (key or scale) is built on the sixth step of a major scale. While a major pentatonic and its relative minor share the same five notes, the tonics are different, the exact same relationship as with major keys and/or scales and their relative minors.

The major pentatonic contains the following steps of the major scale: the first (root), second, third, fifth and sixth steps. The blues scale modifies the minor pentatonic by adding one note, the flat 5th (also known as tritone, diminished 5th, augmented 4th). This blue note is another essential dissonance in the blues.

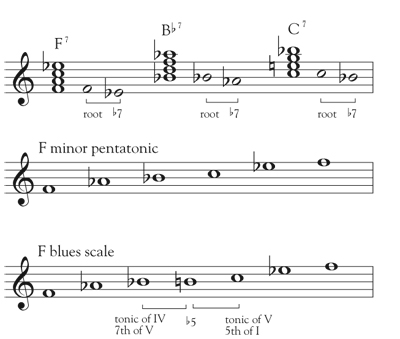

Both the minor pentatonic and its derivative, the blues scale, provide a complete set of notes, albeit limited, for improvising on the blues. While it might not seem possible for a single set of notes from either scale to sound good over all three chords, a quick look at the basic construction of dominant 7th chords shows why this works. The two chord tones in any dominant 7th which virtually define the chord are the root and the minor seventh. By isolating these two notes in each of the three chords in the blues progression, we are left with the five notes of the minor pentatonic scale, merely out of sequence.

This means that an improvisation based exclusively on the minor pentatonic scale (in the tonic key) will work over a blues progression, provided listeners have become accustomed to the dissonance created by a minor 3rd (in the melody) played against a major 3rd (in the harmony). This blue note, and the melodic tension it creates, gives the blues its distinctive sound, as does the b5 of the blues scale, which is simply a chromatic passing tone between the 4th and 5th steps of the minor pentatonic scale. Because of the tritone’s chromatic proximity to both the 4th and 5th steps of the minor pentatonic, a smooth resolution from the unstable interval of a tritone is only one half-step away, in either direction which is classic voice-leading.

Hopefully, this brief analysis of the blues will be a helpful first step for the aspiring jazz flutist.