Playing the treacherous piccolo solo in the Scherzo movement of Tchaikovsky’s 4th Symphony typifies the old adage that orchestra musicians spend 90% of their time bored to death and 10% scared to death. Many piccoloists have learned to cope with this enigmatic solo, but not without tribulations.

Although Jan Gippo has found many alternate fingerings for piccolo, he has never found a special fingering for the treacherous piccolo solo in the Scherzo of Tchaikovsky’s Symphony #4. Trembling piccoloists will be relieved to know one has been discovered that works well for most players.

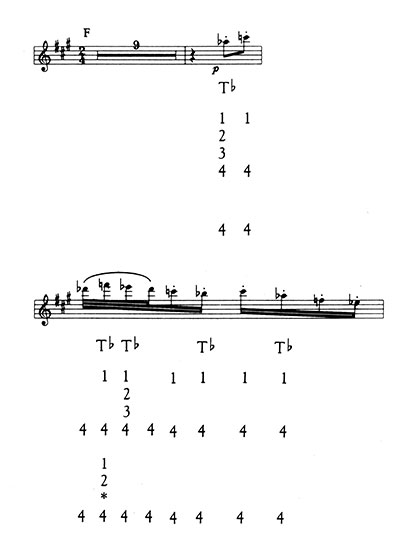

The thumb Bb is indicated; the first trill key symbol is ‘ and the second trill key is *. The graphic keeps a space for every key.

When playing this passage, articulate with a soft legato tongue. Although this unusual fingering for the F3 is quite flat, the note goes by so quickly that the pitch is unnoticeable. One advantage of this fingering is that keeping the G# key open for the first ten notes stabilizes the instrument so it does not roll while playing all the open Bbs. It also sounds at the true piano dynamic that Tchaikovsky indicated.

Many piccoloists perform the solo on Db piccolo, including Jan Gippo of the St. Louis Symphony and Walfrid Kujala, of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Kujala is comfortable playing the Db piccolo, which he has played since high school. Performing the solo on Db piccolo means transposing down one-half step to the key of G major. Former piccoloist of the Detroit Symphony Orchestra Clement Barone prefers the C piccolo sound for the solo and prepared for performances by concentrating on placing the first of the 32nd notes directly on the beat rather than too early. He first practices just the first three notes, then successively adds one more note until completing the entire passage.

Lawrence Trott of the Buffalo Philharmonic recommends practicing the solo at various tempos because from one conductor’s slowest interpretation to another’s fastest tempo, the pace can vary as much as 100%. Lois Schaefer, now retired from the Boston Symphony Orchestra, copes ingeniously with unexpected tempos: after the Tempo I section begins, she plays the passage silently three times, fingering the notes without blowing. She feels it is important to end the silent playing before the clarinet solo in order to have enough time to actually play the solo.

Kujala recalls his first performance of the Tchaikovsky with the Chicago Symphony at the outdoor Ravinia concert series. Although he joined the orchestra in 1954 as assistant principal flute, he switched to piccolo in 1957 when the piccoloist died. The following summer Tchaikovsky’s 4th was scheduled to be performed with C.S.O. music director Fritz Reiner, who hated outdoor concerts and during the rehearsal went through only the first few measures of each movement, and left with a "see you tonight." Fortunately Reiner took a good tempo, all went well, and the maestro saluted Kujala after the solo. Despite his success, Kujala says the initiation was stressful because in those days there was no job protection.

When on tour with the Houston Symphony Clement Barone remembers leaving his swab in the piccolo and nothing came out when he reached the solo. Bonnie Lake, long time piccoloist with the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra, remembers Leonard Bernstein sitting next to her during a rehearsal of the Tchaikovsky at Tanglewood. The moment she began playing the famous solo, Bernstein stuck a lighted cigarillo in the end of her piccolo. During a concert tour in Greece, Jan Gippo was surprised when conductor Jerzy Semkow decided to use the Tchaikovsky Scherzo as an encore, but he did not have his Db piccolo on stage. Although he hadn’t played the solo on a C piccolo for over three years, all went well despite the shock.

Many conductors know this solo challenges even veteran performers. During a four week tour Lukas Foss commented to Lawrence Trott, "You play this very well. I take a different tempo every night, but I can’t seem to throw you." Zubin Mehta once told Miles Zentner of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, "Don’t say ‘*#!@#!’ after you play the solo; someone in the audience might read your lips!" Several years ago conductor Sergiu Comissiona congratulated Ethan Stang, formerly of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra, on his performance. Stang remarked that he found the tempo to be unusually fast. Comissiona asked, "Don’t you have to catch a train by midnight?" On different occasions conductors Fritz Reiner, William Steinberg, and Vladimir Bakaleinakoff told Stang that Tchaikovsky· explained the meaning of this solo in some of his notes and letters as representing a drunken sailor stumbling out of a bar and then relieving himself over a fence.

Kyril Magg of the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, and George Hambrecht, retired principal flutist of that orchestra, recall that William Hebert discovered that transposing the Scherzo solo down a minor third to F major fits perfectly in the last four measures of the same movement. During a rehearsal Hebert played the usual solo and surprised the orchestra and George Szell by adding the transposed solo at the end. Even the usually tyrannical and humorless Szell smiled, but Hebert claims this was only because the conductor had gas. Hebert confirmed all of this and added that Szell had himself cremated so that he wouldn’t spin in his grave every time someone in the orchestra told a story about him. When I experimented with Hebert’s innovation during a youth concert, the orchestra’s personnel manager was not pleased. When I protested that it was funny, he countered dryly, "I never said it wasn’t funny." The alternate fingerings for this tricky solo are recommended, but improvised endings are not.