The flute solo in Maurice Ravel’s Second Suite of Daphnis et Chloé is one of the mainstays of flute auditions and a landmark of the whole flute repertoire. Ravel used the flute constantly in his orchestrations. It could be said that it was one of his favorite instruments, so much so that our beloved pipe appears in a prime role throughout his compositions, whether large orchestral works or intimate chamber music. Flute players’ only sorrow is that he did not write a solo work for the flute, either concerto or sonata.

The flute solo in Maurice Ravel’s Second Suite of Daphnis et Chloé is one of the mainstays of flute auditions and a landmark of the whole flute repertoire. Ravel used the flute constantly in his orchestrations. It could be said that it was one of his favorite instruments, so much so that our beloved pipe appears in a prime role throughout his compositions, whether large orchestral works or intimate chamber music. Flute players’ only sorrow is that he did not write a solo work for the flute, either concerto or sonata.

Maurice Ravel was born in 1875 in southwestern France near the Spanish border. He was fragile looking, small in stature with very fine features. He never married and was said to have been a loner, prone to depression and self-doubt. In 1937 his life ended in the agony of brain illness, which deprived him of his art but not of his consciousness.1 In one of his last major works, the piano Concerto in G (1931), the second movement starts with a long piano solo introducing a nostalgic English horn. Out of that somber mood rises the radiant flute as if to dispel dark thoughts.

In the Septet (1905), Introduction et Allegro for harp, flute, clarinet, and string quartet, Ravel uses the color of the flute and clarinet as a contrast to the harp. A light work, it poses delicate problems of intonation between the two winds.

Ma Mère l’ Oye (1911) (Mother Goose Suite) uses the flute at length, as well as the middle range of the piccolo, illustrating the ingenuous character of these fairy tales.

Boléro (1928) is the most universally known work of Ravel. Its simple but haunting theme is repeated obsessively by all the instruments in sequence over a rhythmic ostinato. The flute has the honor of being the first to play the theme. It looks simple enough, but to play it very softly amid the quasi silence of the beginning is the challenge because it entails control of the color and of the breath.

Last but not least we come to Daphnis et Chloé (1912), a ballet with exposed parts for piccolo, flute, and alto flute in G. In the second Suite the flute solo depicts the loves of Pan and Syrinx.

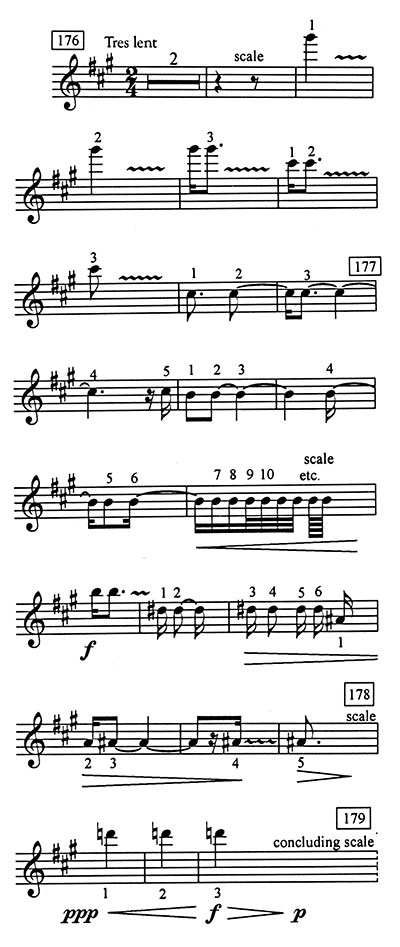

The line of the solo is not, in my view, really thematic. It is built in fact around very few notes: high G#, C#, B, D#, A#, and finally D. Each note is repeated at least three times, sometimes much more. The intervening notes (scales, connections) are of an almost ornamental nature. They grow from a simple pattern to a florid one.

To interpret this beautiful page, the flutist should first identify these skeleton notes, as I have tried to do in the following diagram. Each of these three identical notes should have its own dynamic or color to create a sense of progression (or digression). Vibrato should animate this solo throughout, albeit with a great variety of vibrato speed to enhance changes of tone color, timbre, and dynamics, so that, once again, repeated notes of the same name always have a different direction and an unexpected savor. This will underline the pleading and sensual character of the solo. Notes of the same name, as I call them, should always have a direction, in Ravel as in most music.

The connecting notes should be played with simplicity when there are few and with increasing rubato as the amount of notes increases to return to simplicity when a new skeleton note appears, and so forth.

The starting dynamic indication is p. It should not be played f, no doubt, but a generous mp seems in order, especially in view of the progressions.

The tempo is eighth note = 66, definitely not quarter note = 66. This score is full of mistakes, and the famous E or E# question stems from ambiguity. The flute has E# and the score has a blank space in front of the E. When asked about this discrepancy by a flutist, Ravel is said to have answered, "Frankly, I don’t give a darn…."

I used to play Daphnis in the Orchestre de Paris at least 20 times a year on tour or at home, in different acoustics, and I am sure, or at least I hope, that my interpretations were never the same. I recorded Daphnis many times, with, among others, Andre Cluytens (ca. 1964, EMI), Charles Munch (1968, EMI), Herbert von Karajan (ca. 1972), and Daniel Barenboim (ca. 1975).

1Factual information for this article was obtained in Ravel: Man and Musician by Arbie Orenstein, Columbia University Press, 1975.