To those close to Vaclav Nelhybel, March 22, 1996 was a day of shock and sorrow for his sudden and unexpected passing. Looking back after 20 years, we begin to see the amazing impact he had. He may no longer be with us in a physical sense, but Vaclav Nelhybel is still alive through his music.

He gave us pieces for every conceivable combination of instruments and voices. There are chamber works, choral pieces, orchestral works, operas, and legendary band compositions at all levels. During his lifetime over 400 of his works were published; over 200 are still in the process of publication. The website, www.nelhybel.org, provides a thorough listing of his works.

Vaclav Nelhybel was a direct descendant of an incredibly rich, national musical line of composers that included Dvorak, Janacek, Smetana, Martinu, Suk, Kubelik, Ancerl, and others. Born in Polanka, Czechoslovakia in 1919, Nelhybel was a student both of composition and conducting at the Conservatory of Music in Prague (1938-1942). He also studied musicology at Prague University and the University of Fribourg, Switzerland.

Following World War II he worked for the Swiss National Radio as composer and conductor, and as a lecturer at the University of Fribourg. From 1950-1957 he was the first musical director of Radio Free Europe in Munich, Germany, after which he came to the United States. In 1962 he became an American citizen. He told me once that, upon his arrival in this country, he had several publishing contracts “in his pocket.” “That’s what I started with.” His output grew from there, leading to awards, prizes, and honors of many kinds, including four honorary doctoral degrees from various universities.

The scope and range of Nelhybel’s compositions is overwhelming. He was as much at home writing a piece for a beginning band as he was conceiving a work such as Trittico, written for an advanced ensemble. That he could do either with authority reveals his ability as a perceptive composer with a deep understanding of teaching.

His works are interesting, challenging, and always realistic for performers at whatever level he wrote. His music has character and spirit, both on the surface where communicative melodies abound, and inwardly, where many of the meaty, structural components provide substance. There are contrapuntal features of which Bach would have approved, colorful harmonies, rhythms and meters that dazzle us (attributable, perhaps, to the native musics of the Eastern European cultures that he knew well), organized in formal structures that are the hallmark of masters. Add to that Nelhybel’s fabulous orchestrations, and there is little doubt that his music is something special. Its power and expressiveness is remarkable.

Musicians often describe Nelhybel’s music as fun to play. Often they are amazed by its linear qualities – each line is a melody unto itself but fits within a greater whole. Those lines are designed to be characteristic of each instrument or voice performing them. It is significant that Nelhybel’s music is modern in context and structure, but almost always centered around a tonality or home key. This gives his music a universal appeal to audiences. It is modern music they can relate to, even if it is new to them.

His music is described as fun because the musical lines lie naturally in their ranges and fit the technical capabilities of the performers. Nelhybel had the gift of writing music that makes the performer look and sound good.

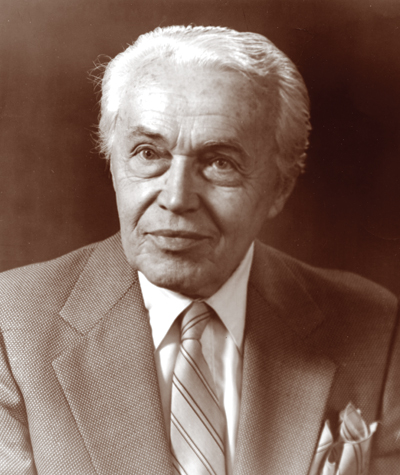

Nelhybel rehearses his Symphonic Requiem with the Fifth Army Band in 1966.

Reflections of Friends

Along with his talents as a composer he was also a gifted conductor. Immediately personable, he connected with those around him, including his audiences. Equally at home with young students and more advanced players, his teaching skills and attractive personality inspired others to achieve their best. As the attraction of his own music was electric, his fame as composer was recognized world-wide.

Frederick Fennell said of him, “Fortunately for the world, every now and then we are blessed with the presence of a creative artist of the stature of Vaclav Nelhybel. In his distinguished maturity and with an in-depth experience amidst great music, it is no surprise to find him arriving amongst us to discover the depths of poverty (in) the wind band’s performance literature. And of course, he burst upon us at a time of great need, work after work of his challenging the profession in endless and fascinating ways. We shall all miss his next challenge but it will remain challenge enough to fulfill the responsibility of the remarkable music he gave us.”

“Vaclav was a genius driven by the music in his mind, heart, and soul,” Frank Bencriscutto reminds us. “He was clearly one of the most important composers for the American concert band/wind ensemble and influenced virtually every composer who has achieved recognition in the past thirty years.”

Frank Battisti, remembering his introduction to Nelhybel’s music in 1960, with a new work conducted by William Revelli, remarked, “And what a piece it was! Everyone present was very excited by this music and the new sounds Vaclav had created. We knew we were hearing a new and exciting musical voice. As the years passed, Vaclav continued to compose exceptional pieces for the wind band and wind ensemble. His music played a significant role in defining the emerging new American wind band in the latter half of the twentieth century.”

Jeffrey Curnow, Associate Principal Trumpet of the Philadelphia Orchestra, offers this delightful remembrance: “It was 1977. I remember having the coveted position of Principal Trumpet in the Northeastern Pennsylvania Regional Orchestra. I was eagerly anticipating working with the great conductor Vaclav Nelhybel and equally as terrified. . . . So I practiced long hours, making certain I was prepared, especially on the solo passages in Nelhybel’s Concerto for Orchestra programmed for that weekend’s performances. . . . When we finally rehearsed the concerto, a work for which he needed no score to conduct, as the moment approached for me to play (the solo), he turned to me with the most amazingly accurate cue I have yet to receive from any conductor, and I missed it. I came in one bar too late. He stopped the rehearsal, stared at me for what seemed like an eternity, and said, ‘Mr. First Trumpet Player, Mr. Principal Trumpet Player, why did you not play when I cued you?’ I looked back at him, straight in the eye, and proudly proclaimed, ‘I made a mistake.’ The orchestra was completely silent. He looked down at his baton and shrugged, ‘Okay, so you made a mistake. Let’s go back and do it again.’ And then he smiled at me – a smile I will never forget. The concert went beautifully, without a hitch. The audience enthusiastically received his the piece. I will never forget the way he conducted. It was straight from the heart. And I will never forget how he inspired me to play straight from my heart. I carry that with me to this day. There is really no other way to be a musician.”

Harold Easley, for years the concertmaster of the West Point Band, shares his memories of special times with Nelhybel: “My experiences with Vaclav Nelhybel spanned over two decades as I grew from an eager student to a professional clarinetist. I knew him as a conductor, composer, and colleague. On the podium Vaclav was an imposing figure. His ability to communicate his desires to players young and old was extraordinary. His booming voice, Czech accent, and old world elegance were memorable. Privately he was warm and witty and generous with his time and talent.

“I was an immediate fan in my first encounter with him when he conducted the Houston Concerto for Orchestra with the Texas All-State Symphony. While as a student at Lamar University in the early ‘70s, I wrote to him asking if he had written a clarinet piece. To my surprise he responded, saying it was an interesting idea, and generously included two LPs of his band works.

“In 1980 while I was the principal clarinetist of the West Point Band, I again contacted him to ask about woodwind quintets. He promptly responded with a signed copy of one of his quintets and a few days later he phoned me to ask if I would premiere his Concerto for Clarinet and Winds at the NYSME convention. I was thrilled. In the weeks before the start of rehearsals at West Point, I worked with him at his home in Connecticut, going over details of the score. He gave me many musical insights into the piece and also shared what life had been like in Prague, in the 1950s. He also explained that this clarinet concerto was dedicated to his dear friend, the late Frank Stachow, who helped him start his career in America.

“Vaclav was a favorite guest conductor of the West Point Band and returned to conduct the clarinet concerto several times over the years. I will always remember him as an exceptional composer and conductor as well as a generous musical advisor and friend.”

With a typical Nelhybel remark, eyes twinkling, “I know you’re a saxophone player but you read music, don’t you?” Mario Bernardo, classical saxophonist, tells this: “There are people who mark your life as a musician and continue to shape our music experience throughout our lives. . . . My first experience with Vaclav’s music was both terrifying and exhilarating, in that order. I still remember that moment he would stop us in mid-rehearsal. The pregnant pause, the feeling of the world standing still in those few seconds of silence as we awaited his judgment, and then the sudden feeling of relief when his first exclamation was, ‘Horns!’ and not ‘Saxophones!’

“Along with my friend, composer Hubert Bird, we would often visit Vaclav at his home though as often as not we would meet him in the evening at Vaclav’s favorite late-night Greek diner. There we would have several omelets, the world’s most dubious coffee, and were enveloped in the permeating aroma of Vaclav’s favorite cigar, a ritual repeated often over the years.

“Through a variety of coincidences and good fortune, I was performing the Glazunov Concerto with an orchestra in the Newtown, Connecticut area. Vaclav attended the performance and somehow we began to discuss the commissioning of a new work for saxophone and strings. Vaclav was interested in creating a significant work for the classical saxophone and in working with me, a relatively unknown saxophonist just out of college, with very limited commissioning resources (except paying for an omelet and a coffee or two). I had just learned, however, that I would be performing in Portugal on a year-long Fulbright scholarship, and this would become the perfect occasion for the 1986 premiere of the new Rhapsody for Saxophone, in a performance with the Radio Difusao Symphony Orchestra of Portugal.

“Throughout the year before leaving I had the opportunity to visit Vaclav at his home, playing and demonstrating various saxophone techniques while he took notes for later consideration. It was like being in a studio watching a painter as he experimented with various textures, colors,, and brushstrokes, but his palette was me and my saxophone.

“I do miss watching his creative process, trying to decipher the quickly-jotted-down scribbles as he feverishly put them on paper. I do miss him, his sage advice, his humor, the opportunities he gave me, and maybe most of all our late-night sessions at the diner.”

Personal Reflections

I vividly remember my first meeting Vaclav Nelhybel. On an extremely windy afternoon in the fall of 1981, in Jorgensen Hall at the University of Connecticut, a performance was being prepared that included a work of mine. Onstage were the university choir, the conductor, the accompanist, and a solo clarinetist. I was seated about halfway back in the auditorium.

At one point the conductor stopped the rehearsal to adjust something in the music, and asked me to come to the stage to answer a question. As I rose from my seat the door at the back of the auditorium opened; the howling wind outside could be heard clearly. Walking toward the stage, I turned briefly to see if the door had simply blown open on its own, only to discover a man in a rumpled, grey suit (though wearing a tie) standing there, his hair completely in disarray from the wind.

I went to the stage, thinking someone had wandered in to escape the windy day. After resolving the problem down front I returned to my seat, only to have the man motion for me to come to him. I really didn’t want to, but I did. He had a specific question about the music, which told me that he was listening carefully and had a good ear. The man was Nelhybel. He put out his hand and shook mine, introduced himself, and that was our beginning.

Over the following years the two of us became very close; he introduced me to numerous people and situations. Many of those opportunities have influenced my professional career, and I am forever indebted to him for his interest, friendship, and mentoring. I learned from him many steps and procedures that only come from experience. The many times we met at the Midwest Clinic, the numerous concerts we attended in various places, and the experiences we shared – all are cherished today as special memories.

The day he left us I was in Dallas, representing a work of mine at a convention, doing what he taught me well to do. Returning home three days later I learned that, even as I had thought of him while going to the podium in that far-off place, he went away at almost exactly the same time. At this twentieth anniversary of his passing we are only three years away from the century mark of his birth.

In his final years Nelhybel and his family moved from Connecticut to their new home in Pennsylvania, near Scranton. There, he became the composer-in-residence at the University of Scranton, a Jesuit university. It is significant to note that his early education was under the guidance of the Jesuits. At Scranton, he became the colleague of Cheryl Boga, the university’s Director of Choirs and Bands. Boga is a long-time champion of Nelhybel’s music, and has presented innumerable performances of his works. A close personal friend, she has contributed importantly to the promotion of his legacy.

To me, he was a guide and mentor of a most special kind. His wisdom and counsel were always accurate and our conversations, so precious now in my memory, revealed an artist of great vision and depth. I cherish every moment we spent together. He was my friend, and I miss him.