Composer Roger Cichy has almost 300 compositions and arrangements to his credit and has received numerous composition awards from The American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers. He is in demand for commissions and frequently works as a guest conductor and composer in residence. Cichy is also a former band director, having taught instrumental music in the Mars, Pennsylvania schools and at both the University of Rhode Island and Iowa State University.

As both a composer and band director, what performance practices do you find most important?

Style is such an important aspect of music performance, but our notational system does not adequately communicate style well. I have found it extremely important to provide the ensemble with as much information about each piece as possible, whether it’s program notes, research about the work, or better yet, contact with the composer. I have found that describing what a section of the piece represents saves me a lot of rehearsal time when it comes to style problems.

In 2008 I wrote a piece called Beachscapes, a three-movement work with each movement about a specific beach in New England: one in Connecticut, one in Rhode Island, and one in Massachusetts. I visited the Massachusetts beach just after a hurricane, so the waves were extremely high. There were many people trying to surf, although only one out of every 20 seemed to know what he was doing. As I kept watching people wipe out, it seemed comical, so I built that into the music. A melody goes along and builds, and the wipeouts are represented by a dischord at the end of the phrase, along with a bass drum roll and cymbal crash representing the crowning of the wave.

A band I worked with just didn’t seem to have the push to make it sound like that. I explained the inspiration, suggesting that they were the surfers, out wobbling around on a board when a giant wave suddenly came along and they took a spill. I didn’t say anything about needing a stronger crescendo or aiming toward the final chord, both legitimate things I could have said. But we played it, and students made it sound the way it should. It had the right style and direction.

The middle movement represents a very calm beach in Connecticut. There is little activity; people lie around and forget all their troubles while the world passes them by. When I told students the melody should be delicate, as though they didn’t want to be interrupted in their meditation or escape from pressure, the music fell right into place the next time they played it.

Musicians who understand a piece will play it with a better sense of style. A musician is an actor, acting through the music. There are millions of life experiences, and there are just as many styles possible in music. It makes a big difference to put yourself in character and understand how the music is supposed to sound. Playing without style is like an actor who didn’t do any character study. A musician who understands a piece will play it better.

Which aspects of teaching have most affected how you compose?

Attention to detail is often lacking in ensembles. As a composer, I am adamant about how a particular note should sound – how loud it is, how long it is, how accented it is – so I take a lot of care in writing dynamics and articulations for this very purpose. These are the details that produce the results the composer intended and turn printed notes into real music. However, it surprises me to hear a performance missing many of these critical areas, almost as if the ensemble focused only on notes and rhythms.

I was amazed at how the teachers in my daughter’s Suzuki program paid attention to detail, even with three-year-olds. It wasn’t performance-based education; students progressed at their own rate, but teachers paid attention to detail and made students discriminate about which sound they liked better and why. It was not just overall, but for specific phrases and notes, asking “is this staccato too short?” Students can easily learn to make such judgments.

Most bands are extremely performance-oriented. Everything is pushed toward for performance, even with beginners who have to get ready right away for Christmas concerts. Directors quickly push through the literature, and as a result students never learn to think beyond notes and rhythms. For example, if articulations are marked, work for consistency. Students may play staccato passages short, but some will play shorter than others; the key in this case is to work on matching note lengths. These concepts should be taught at an earlier age so students know to always think about their sound.

I have conducted a lot of music with too many musical details left out. I’ve even seen pieces that do not even have a dynamic marking, tempo indication, or style marking at the beginning. This leaves too much room for interpretation by the musicians and makes it harder for a conductor to work for consistency without having to edit the parts. If I hear a performance of my work and find several areas that are different than I intended, I usually question what things I should have notated to better communicate my musical intentions.

I’m a stickler for such detail when I teach composition. Students’ projects are immediately returned if they don’t have a title, a starting dynamic (at least – hopefully they’ll have others as well), tempo and style markings, and their name as composer or arranger on it. If students turn in a paper without one of these things, they will get it right back.

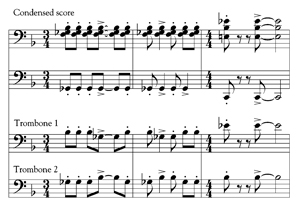

I have also seen and played a lot of boring and lifeless passages that repeat one or two notes for a while. As I compose, to avoid this problem, I find myself cross-voicing parts, especially in instruments that divide, to make the music more interesting. It works the best with a texture containing syncopated figures. It doesn’t work as well on an instrument playing straight eighth notes. Having players switch voices when a note is accented makes the music more playable, because no one sits on one note. It also strengthens the accent more. The one thing that convinced me to continue doing this was a film music class I took taught by Buddy Baker, a Disney film composer for many years. With cross voicing he always said, “If it plays better it sounds better, and that’s what it’s all about.” That’s what makes cross voicing great – it’s not just to ease your conscience by giving players a slightly better part, but there really is a musical effect from it. However, I did get myself in trouble cross voicing with an orchestra. The second violins were much weaker than the first violins, and when the notes switched it sounded like an intentional change rather than the even sound I was going for.

What do you wish more directors would know about commissioning a composer?

You don’t have to have the best band to be able to commission. Many bands can use it to their advantage, especially younger bands that are building. Any group with the interest and the means should commission. One good reason to commission a work is to get something written specifically for an ensemble’s instrumentation.

One trick I use when I write for a young band is to write just above their playing level. I do this because a commissioned work is generally going to receive more rehearsal time, more work, and more energy than any other piece they have on the program. I won’t write a grade 4 piece for someone who commissions a grade 3, but I might push the trumpets up in range a bit or take a chance somewhere. If it’s just a straight grade 3, students won’t grow as much.

Also, directors should look at the overall experience rather than just getting a piece for their group. There is more to gain from it. I like to have students look at my handwritten scores to see smudge marks where I’ve erased things and crossed-out bars I didn’t like or squeezed-in measures because I wanted to expand something. When I am commissioned by someone in the area, after I get the piece sketched out I will go sit in the school library or a practice room and score the piece so students can watch.

For some commissions I’ve gone to the school without a single musical idea but just talked to the students and developed something from those conversations. This gives students the ability to see the process from the very beginning. At this point I might have a couple ideas to toy around with but am otherwise a blank slate. Students see these beginnings, then I tell them that in a month they’ll have a piece; a month later they’ll be working on it, and a month after that they’ll perform it. It is powerful for students to see that the commissioning process is a journey.

Usually if a commissioning ensemble is a long distance from my home, I’ll come in for the premiere and the last couple rehearsals to talk about the piece and show students sketches. I’ve done that with festivals I’ve directed as well. When we’re rehearsing one of my pieces, it’s amazing how many students come look at my sketches during a break.

I will usually tell an ensemble that I have composed the piece for them, but it is not music until they play it. They are the other half of the music-making process. It is their responsibility to take my thoughts that are encoded into notation and turn them into music. Essentially, the success of the premiere performance is a huge responsibility that they have to shoulder; I’ve done my part by creating the music, now they have to recreate it. To further emphasize my point, I have every member of the premiering ensemble sign my score.

What do you wish was different about most bands?

Many bands are extremely top-heavy. I have been forced to use bass clarinet and baritone sax to double the bass line as much as possible, when these instruments might be better suited for something else. I remember my first middle school band; the lowest instrument was a tenor saxophone. We were able to purchase a bass clarinet and a baritone saxophone and found two students were eager to switch; we also recruited a student to switch to tuba. The difference in sound was amazing. Everyone’s eyes raised and one student even said, “Wow, we actually sound good now!”

I have presented clinics on the idea that the bottom of the band has shifted up. As part of the clinic, I play recordings of a piece everybody knows. One recording is by an extremely top-heavy band, and it just doesn’t sound good. If you think about the music that bands or orchestras play, the balance point between lows and highs is typically around middle C. If you watch the sound on an equalizer, it should balance around there. If you think about a band and the number of instruments that play mostly above that balance point compared to the number of instruments that play below it, you understand the problem.

Orchestras, string quartets, and brass and woodwind quintets are balanced well with highs and lows. Brass bands commonly have around 28 players, four of which are playing tubas. When you think about how beautiful these groups sound, you have to realize that 1⁄7 of the ensemble is made up of tubas. If you translate that to a concert band with 60 players, you need about eight tubas to get the same depth of sound.

My advice is to do anything you possibly can to get bottom in your band. A 40-piece band with only one tuba, no matter how good the player, is not going to be balanced. A 65-piece band with only one bass clarinet or even two tubas is not going to be balanced. Use a contrabass clarinet if you have one; use a string bass if you have one. It is possible to prepare thoroughly for concerts or contests and still not sound as good as another band that may be less refined but has sufficient low instruments.

My advice is to do anything you possibly can to get bottom in your band. A 40-piece band with only one tuba, no matter how good the player, is not going to be balanced. A 65-piece band with only one bass clarinet or even two tubas is not going to be balanced. Use a contrabass clarinet if you have one; use a string bass if you have one. It is possible to prepare thoroughly for concerts or contests and still not sound as good as another band that may be less refined but has sufficient low instruments.

As a composer, what have you gained by majoring in music education?

The one thing in particular that helped me was all the instrumental methods classes I took for my music education degree. Having your hands on an instrument and actually playing it is a lot different than studying about it. If I had the time I would study one instrument per year. It would be nice to study harp, trombone, oboe. Playing an instrument is completely different from studying it in a text book.

Young composers always have problems with using instruments in their most musically useful and idiomatic ways. They tend to know the ranges of each instrument, their tone color in various ranges of the instrument, and many of the special effects, but a lot of the knowledge of the instrument is never realized because they haven’t actually played it.

This is especially true for percussion. I tell my students is that learning to understand and write for percussion is like buying a big toolbox with all kinds of tools. When you work on your car, you don’t use everything in your toolbox; you only use the tools that are appropriate for the job. When I write for an ensemble, I know what percussion is available and how to use their multifaceted colors and effects, but only use what is appropriate for the overall musical results for that piece. The worst thing to do is adding percussion simply because it seems like there should be something thrown in. I also see composers not write enough percussion, and I have listened to pieces and caught myself making up percussion parts in my mind as it’s being played.

When I’m working on melodies in a composition, I pick up my saxophone or trumpet and play through the line. I frequently make small changes to what I have written after seeing how it feels to play through the line.

When I’m working on melodies in a composition, I pick up my saxophone or trumpet and play through the line. I frequently make small changes to what I have written after seeing how it feels to play through the line.

People use technology to a disadvantage. I have many students who use music writing software, but the playback does not represent how the music will really sound. Computer playback does not have to breathe or cross the break, does not miss accidentals, and can hit high notes with ease. I think people use the software as a crutch and then say, “That’s not the way it sounded on the computer,” when they hear a real performance of their piece. Try to get actual performances of the work rather than base it on computer playback. I want to do a clinic where I play a piece through music-writing software and then play a recording of a group performing the same thing and ask people to tell me what they heard.

I only use a computer notation program to generate the individual instrumental parts and to use the playback feature to listen for any wrong notes that may have crept in. I still score by hand primarily because I want to be able to notate sounds I want quickly: a loud, accented, but short quarter note in the first trumpet can be hand-written much quicker that inputting the note, then adding the appropriate dynamic and articulation markings, which in some cases can be several steps.

How much do you work with directors working on your pieces?

I receive a large number of e-mails from directors asking specific questions about a piece of mine that they are working on. The internet makes it relatively easy to get contact information on most living composers. Before the internet, when I was doing a commission, the group involved would mail me a tape, and I would dub in some comments and send it back to them.

Now people just e-mail me, or directors will occasionally set up a telephone conference with me on speakerphone so all the students can hear me. It works well because the directors always prepare the students to talk to me and set things up as if I were going to be there in person. Although telephone conversations are most common, I use Skype and iChat and have done video conferencing in which the ensemble members can see me as I speak and address their questions. Distance is no longer a problem. The interaction between the composer and musicians is a great and educational use of technology.

I believe electronic delivery of music is right around the corner. There’s not going to be a printed page, people will have a screen with the music on it, and means that you could theoretically have colorized music – dynamics could be in one color and articulation markings in another. I tell people that 20 years from now there won’t be a printed page of music around. Band directors will be able to purchase and download new pieces from their offices, e-mail the parts to everyone’s stand, and rehearse it the same day. There will no longer be lost parts the day before a concert; the only worry will be power outages.

What are the biggest advances for bands today?

There is a great wealth of good literature available for concert band primarily because there many composers writing for this idiom. Even on the professional level, there are many more composers being commissioned for band works than composers being commissioned for orchestral works. It sometimes seems that the only new music being written for orchestra is film music. Professional orchestras are not really advancing the art the way bands do.

Another major influence is the number of recordings of band works. Digital recording has made it very economical for ensembles, especially at the university level, to release good recordings of band works, including recently composed pieces. When I began directing a high school band in the 80s, there simply were no recordings and you never got a chance to hear a new piece other than the publisher’s promotional re-cords, which in many cases were marginal at best. Now you can obtain and listen to several recordings of a band work, a real asset to band directors. I’ve even used YouTube to check out a few pieces. The sound quality might not be the best, but you do get to see the conductor direct the piece.

When people go to Midwest, they take notes in their programs. When they get home and review everything, they might say, “This will be good for my group” or “I don’t have the clarinets this year, but I should keep it in mind.” Any concert will be a good opportunity to find new works; this is especially true at state or national music conferences with many scheduled performances.

Word of mouth is always good. I have a lot of respect for Jim Cochran at Shattinger’s. He will always suggest good-quality music when you ask him. If you have a dilemma with a weak or strong section or a wonderful soloist, he can think of a piece that would be perfect. He can even recommend pieces he doesn’t have; the man’s knack for recalling good-quality literature is amazing.

It used to be that way in all the publishing houses, such as Carl Fischer in downtown Chicago. When you walked into these places, there were a number of people who could do that. I remember one trip to Carl Fischer 20 years ago, when I needed a score for Scythian Suite by Prokofiev; without looking anything up, the clerk asked what edition I wanted and he named about three. With computers and the internet, those days are gone.