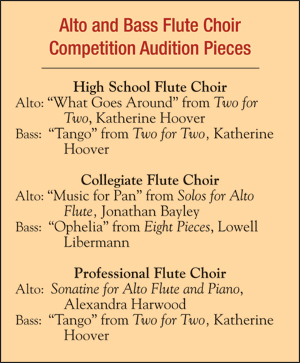

The National Flute Association holds competitions for participation in convention flute choirs. The High School and Professional Flute Choirs have been a staple of conventions for many years, but in 2009 the Collegiate Flute Choir will make its debut. It is open to all full-time undergraduate students, regardless of their majors. Entry forms for all three flute choirs are available at http://www.nfaonline.org/competitions and must be postmarked no later than February 14th, 2009.

With the entry form include three duplicate C.D.s of the required pieces and the $35 fee. While this article focuses on the alto and bass pieces, a C-flute piece is required for each recorded audition. The High School C-flute pieces are the “Allemande” from J.S. Bach’s Partita in A Minor and the “Chante” from Catherine McMichael’s Académie of Dance. Collegiate entrants record Enesco’s Cantabile et Presto, and Professional Flute Choir hopefuls include the first movement from Stephen Lias’ Sonata for Flute and Piano. Piano accompaniment is expected on the C.D.

Alto Flute Audition Pieces

“What Goes Around” from Two for Two by Katherine Hoover (Papagena) High School Flute Choir

The opening should be playful and energetic. The first measure tosses quarter-note trills back and forth between piano and flute, and the next several measures are all sextuplet 16ths. It is easy to choose a tempo that is too fast and quickly find yourself in trouble. There are many places in the piece where sextuplets are passed back and forth with the piano, so precise entrances are important. Practice with a metronome to keep the entrances strictly in time so you don’t lose momentum.

The piano starts the dreamy middle section in bar 41. Ask the pianist to soften his touch and use the sostenuto pedal with delicacy. There are many opportunities for expressive phrasing in this middle section. Experiment with dynamics and slight delays and hesitations on notes to discover and develop what appeals to you. Again, metronome practice will help you avoid getting too slow.

Maintain the accelerando in the short cadenza until its culminatation on the low C# in measure 86. The music gradually builds, and the opening trills magically reappear as you drive to the end of the movement.

The two most challenging measures of the piece are 101 and 102. Like any difficult passage, begin practicing these measures with different rhythms and articulations right away so that they are ready when the rest of the piece is done. I use harmonic fingerings to correct the pitch on the forte notes at the top of the run.

After this flurry of notes, back off slightly. I imagine the next measures, 104-108, as sounding like hail on a metal roof. The music builds again and the tempo presses ahead, as the piano hands off its eighth notes to the flute. Be sure to honor the silence in the next to last measure and play the final two Cs with chutzpah. I have been known to stomp my foot on the last note. Add fingers to bring the pitch down.

“Music for Pan” from Solos for Alto Flute by Jonathan Bayley (ALRY) Collegiate Flute Choir

This is a charming piece written in a Renaissance style. Listen to some Renaissance dance pieces in 3/4 or a similar meter to get the feeling of lightness and placement. Look up gioioso (joyful), which appears at the beginning, to understand the composer’s intent. Think about how a recorder would sound playing this and consider how much you might want to emulate that sound and quality of articulation. In a performance, a triangle or finger cymbals would be a colorful addition. There are few dynamic markings on the first page of the piece. Consider adding an echo at measure 37 because this material was just heard four bars before, followed by a forte in measure 41, where the melody becomes more adamant. Decrescendo in measures 47 and 48, which will bring you to just the right dynamic to make the marked crescendo in measures 49 and 50.

On the second page, the Lento section has no bar lines and should be treated like a cadenza. The first and second endings are confusing until you realize that there are no repeat signs. Study the second page carefully to determine what to do at the first endings that have no repeat signs, and take note of the Segno as you pass it.

Sonatine for Alto Flute and Piano by Alexandra Harwood (Progress Press) Professional Flute Choir

This piece was commissioned by Andrea Graves and premiered at the 2008 N.F.A. convention. While through-composed, it has four sections.

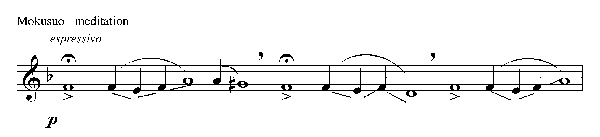

Mokusou-meditation: The slow sections of this movement emulate shakahachi flute playing.

Recordings of this style will help you learn the sound you are trying to imitate. Pitch bending is easy on a shakahachi because of its open holes, but not so simple on an alto flute unless you have one with open holes. If you are one of the few with such an instrument, slide the entire hand on and off the keys rather than just one finger at a time.

Those with closed-holes can bend pitches with the lip; the half step opening F to E is easy, but the slide up from F to A is more of a challenge. Depressing the F# key while playing F will help. From A flat to A, raise only the left-hand fourth finger, not both fingers as you would normally do. It takes a fair amount of practice to learn to ooze off the keys to create the desired effect. A diffuse tone during slides will mask the transitions. The first slide pattern is repeated many times, so get very good at it.

Uta-song: Practice singing this section for ideas on how to use vibrato, shape phrases, and rubato. Pitch problems because of the high range in measure 95 and 105 will require special attention.

Gugaku-Japanese Imperial Court Music: This section starts with a return of the opening pitch slides and should be even more dramatic. I had questions about accidentals in this section and Andrea Graves provided the following answers: All the Gs in measure 114 are sharp – not just the two that are marked. All the Es in measure 117 are flat, and all the Ds in measure 118 are flat. The Fflat at the end of 116 carries over to measure 117 and the Dflat at the end of 117 carries over to measure 118. Assume that accidentals carry through the measure.

Buyou-dance: Keep this charming and rambunctious movement light and fluid, and honor the dynamic markings. Beware of pitch problems in the third octave in measures 147-150. Those players with curved headjoints might try harmonic fingerings a fifth lower in these forte passages to bring the pitch down. The trills in measure 167 and 215 should be from Dflat to Eflat.

There is one measure of flutter tonguing in 214. Those who have trouble with fluttering can either play the measure normally or try double tonguing as a substitute. Growling or gargling works for some people, but it doesn’t seem to fit here.

Bass Flute Audition Pieces

“Tango” from Two for Two by Katherine Hoover (Papagena) Professional and High School Choirs

To get the feel for this slow, sensuous tango, listen to recordings or find D.V.D.s to watch. The website (http://lcweb2.loc.gov) has videos of tangos on clip #80–82. Ask your pianist to watch and listen as well to understand the mood. Gliding, languorous movements interrupted by abrupt changes in direction typify the tango.

Dynamic contrasts are the key to a successful performance of this movement. Create gestures that are like the tossing of a head, long flowing arcs or sly glances. Do all this with extreme dynamic contrasts, by lingering unexpectedly on a few notes, or through sudden increases and decreases in speed. A sudden diminuendo on one note is like a haughty move of the head or a sigh. If there is a written accent, make the most of it; treat accents almost like a fp.

Decide where you want to use your most passionate vibrato and where to be cold and distant. It is your job to tease the audience. Look for places to move ahead and places to hold back. I especially enjoy two spots where the flute is in parallel fifths with the piano–bars 44-46 and 117-118. I throw in a few glissandos from time to time to heighten the effect of sliding movements. The quarter-note triplets should be broad and lazy. There are many instances of repeated notes; record yourself to ensure that they are distinct.

The piano ends the movement with a soft downward moving gesture. I find it heightens the suspense to delay this last entrance and to play it as softly as possible. In performance, be sure to hold still after the final piano notes to allow the audience to contemplate what they have just heard.

Microphone placement will be important when recording this piece so that the bass flute can be heard above the piano.

“Ophelia” from Eight Pieces by Lowell Libermann (Theodore Presser) Collegiate Flute Choir

There are over 15 instances where the right-hand pinky finger slides between low C and Eflat. To smooth this exchange, prepare beforehand by rubbing the little finger behind your ear to put some oil on your finger.

The indicated tempo is quarter =c. 63, and I suggest practicing with a metronome set on the eighth at eighth =126. When you are comfortable playing the piece at that tempo, you can decide where to speed up and slow down to honor the indicated Lento con molto rubato.

The first three 8ths on line 2 are straight 8ths – each should receive one beat at eighth=126. The 8th-note triplet patterns that follow should be spread over two 8th-note beats. At the beginning of the third line, start thinking in quarters rather than eighths. In the last group of line 4, notice the group of four straight 8th notes amongst the triplets. They should be played at the same speed as the triplets that precede and follow them. For extreme accuracy, set the metronome on 189 to the triplet 8th.

Notice the numerous fermatas. Some are on breath marks, some on notes, and some are on rests. I understand a fermata on a breath mark to mean take a relaxed breath, but not more time than that. It is logical that a fermata on an 8th note or rest is shorter than one on a quarter note or rest. Be careful not to put in extra time where none is indicted. The rests without fermatas should be the correct length.

Many notes have tenuto marks, which technically means to hold the note full value. Here, I think the composer is pointing out the melody. By lengthening or adding extra warmth to these notes, the listener will be more aware of the melody and its development.The last line starts piano and ends pianissimo followed by a diminuendo. To make a more effective diminuendo, I suggest starting a bit louder.

Remember to make the best quality recording possible because competition for the New York convention will be especially tough. Use a recording studio that has excellent equipment, soundproof rooms, and experience in recording classical music. Good luck!