“A composer should write with certainty. If the opening leaves the listener not knowing if the work is fast or slow, agitated or calm, or loud or soft, there is confusion.”

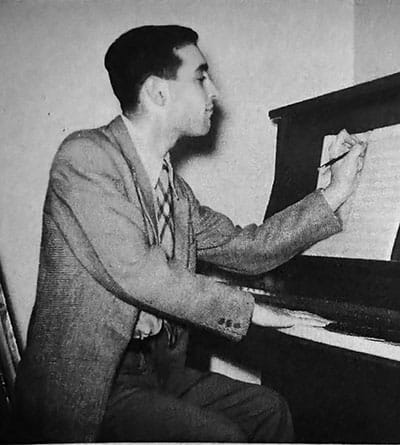

William Schuman

We rediscovered some intriguing interviews by composers in our pages over the past 80 years. Here are their perspectives on composing, interpreting, and performing great music, and the journey that led to composing their own music.

Claude T. Smith

Claude T. Smith completed over 110 compositions for band, 12 orchestral works, and 15 choral pieces.

What makes for a great musical interpretation is often elusive. I always like to work for the correct and most musical interpolation. At times I feel I’m very good at it, and at other times I know I have missed completely.

When I was teaching in high school, I entered a brass choir in the state music festival/contest. We had prepared a work in great detail and were confident of our performance. The day came for us to be judged, so we have it our best. We felt sure that we had our I, the Superior rating. About an hour later, one of the members of the ensemble came flying down the hall with an incredulous look on his face. He said he had seen our rating, a II. I couldn’t believe it, so I went to the festival headquarters to review the rating sheet. For sure, our rating was a II. In reading down the adjudication sheet, I saw that all areas of the performance were graded I, except interpretation. A comment at the bottom of the sheet read: “Fine brass choir and good choice of music, but I didn’t care for your interpretation.” The fact that the judge didn’t like my interpretation was a real shock, for the selection performed was one of my compositions. (November 1982)

Libby Larsen

Libby Larsen is a Grammy award-winning American composer with a catalog of over 500 works in virtually every genre, ranging from intimate chamber pieces to large orchestra and opera.

“Early in my career, when I wrote the double barline at the end of a work, I considered the compositional pro-cess to be 100% complete. After gaining greater experience, when I finish this step, I consider the work to be about 93% complete.” When the piece is rehearsed for the first time, she often adjusts parts for better balance or transitions. “I do not consider the composition to be complete until the work has been presented to an audience.” (September 2010)

H. Owen Reed

H. Owen Reed was on the composition faculty at Michigan State University for nearly four decades. He lived to age 103 and is best known for La Fiesta Mexicana.

As you developed as a composer, were others much of an influence on you?

I learned much from the composers with whom I studied, including Helen Gunderson, Howard Hanson, Bohuslav Martinu, and Roy Harris. I studied 16th-century counterpoint with Gustav Soderland, and contemporary styles with Burrill Phillips, Aaron Copland, Stanley Chapple, and Leonard Bernstein. Even when our individual philosophies differed, each of those people greatly influenced my writing. During a long private session, Arnold Schoenberg convinced me to write my scores in C, a practice I continue today. Finally, I think most composition teachers would agree with me when I say that students are always a fertile source of inspiration.

What are the greatest challenges as you work to develop a piece?

I strive to write music that is strong in all five basic parameters: harmony, melody, rhythm, form, and color. The main challenge for any composer writing in any style is to maintain good balance between unity and variety. Even if these prerequisites are met, not everyone will like our opus.

After a fine performance of my For the Unfortunate at Michigan State University, one of my graduate composers commented that an older lady turned to her friend and said, “The only thing unfortunate about this piece is that it was ever written. Although this particular work features a free type of serial writing, tone clusters, an improvisatory percussion ensemble, and non-measured sections, most comments have been complimentary, and I still consider this work equal in quality to the well-received La Fiesta Mexicana. You win some and you lose some. (September 1998)

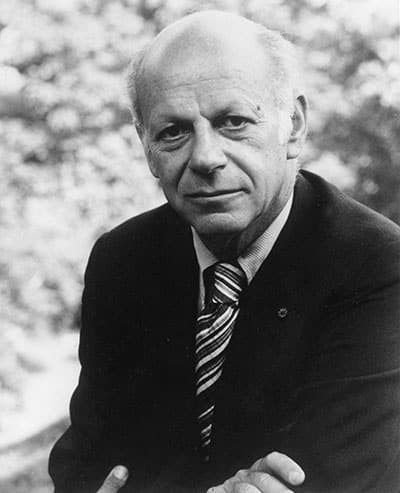

Martin Mailman

Martin Mailman taught for 34 years at the University of North Texas in Denton as Coordinator of Composition, Regents Professor of Music, and Composer in Residence.

How did your interest in writing music develop?

In high school I played trumpet and always sought the creative aspects of music. In a Literature of Materials class at Juilliard, the professor gave an assignment to write a little piece. The first class after we turned in the assignment, he asked, “Who’s Mail-man? I thought he wanted to usher me out the door, but he said my work was very good. I enrolled at the Eastman School as a trumpet major the following fall and later switched to composition.

How much is composing an innate ability or a skill that can be learned?

As a composition teacher of 40 years now, I’m still not sure I can answer that. I have been surprised by students so many times. As with a garden that blooms at different times, sometimes a person who I have great expectations for is later a great disappointment. Some others, I didn’t expect to be very good, but they turned out to be excellent composers. Everybody has a creative side to them – how much of this they have and how creative they are and committed to composing are variables.

A teacher can influence a student by being an example of someone who is creative and showing enthusiasm for their work. There have been students who really wanted to be composers, but I have had to explain that I didn’t think they should.

In working with students, I have been able to maintain a youthful vigor and a love for teaching. This is the only way I could repay what my teachers did for me when I was a novice composer.

How can high school or middle school directors encourage students to compose?

A splendid opportunity for them is to write something for just solo clarinet without accompaniment or a short little piece for two trumpets. If directors take a few minutes out of a rehearsal to let them perform the work for the band, this is a great way to get started. Writing a piece for full band is far beyond the skills of most people. Most of my early pieces were solos or songs and not for big ensembles. As I started having my pieces played or performed, composing became a vicious little habit. I became addicted to this for life. (October 1999)

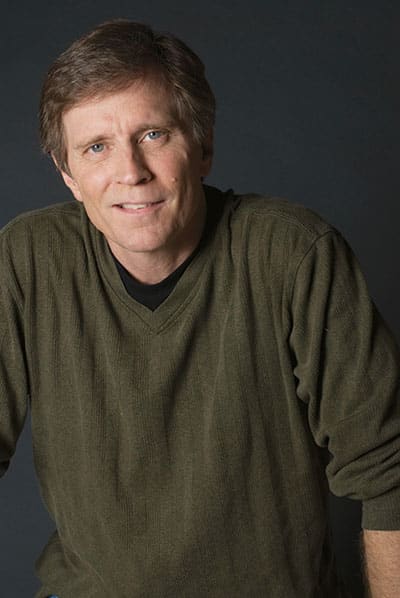

Frank Ticheli

Frank Ticheli was Professor of Composition at the University of Southern California’s Thornton School of Music for more than 30 years.

How did band composition figure into your training at the University of Michigan?

Michigan has a strong legacy of band music, and one of my main teachers, Leslie Bassett, composed many works for wind ensemble. At some schools band music may be discouraged, but not at Michigan. I petitioned to write a dissertation composition for wind ensemble instead of orchestra, and it was granted without any fuss at all. Robert Reynolds conducted the premiere of the work.

I grew up playing trumpet in bands and orchestras in public schools in Louisiana and Texas and have always been part of always been a part of the band culture. As an undergraduate and master’s student, I didn’t write any band works because I wanted to branch out. I came back to band music midway through my doctorate, and in my late 20s, I composed a work for trombone and band, Concertino, and Music for Winds and Percussion for my dissertation.

After the doctorate, what prompted you to compose for young people?

After writing several band works that were extremely difficult, my first attempt at an educational piece, Fortress, was uncommonly successful. When bands started to invite me to guest conduct, I became hooked on working with young people and decided that this is part of what I wanted to do. I do not view writing music for young bands as an artistic compromise. I don’t mean to be melodramatic, but I believe that composers can contribute to society. If writing this music for students helps band directors to keep children off the streets, I’m proud of that. (June 2001)

Elliot Del Borgo

Elliot Del Borgo taught instrumental music in the Philadelphia public schools and was professor of music at the Crane School of Music, where he held teaching and administrative positions from 1966 to 1995. He wrote more than 600 compositions.

How did your studies with Vincent Persichetti help to shape you as a composer?

It was wonderful to learn from a musician of that stature. Persichetti was one of the first composers to treat bands as more than just orchestras without strings. His ability to write percussively without using a great deal of percussion has influenced many other band composers, and his scores typically call for smaller percussion sections than many contemporary pieces do.

The percussion parts are busy, though.

Yes, but they are so appropriate. He can provide a wonderful setting with just a few strokes on a wood block. His harmonic sense is also magnificent. I was fortunate enough to be a student of Persichetti’s when he completed his book on 20th-century harmony. We went through the whole text while it was still in manuscript form.

As a guide, that book is almost unequaled.

It contains so many logical concepts about 20th-century harmony, even though people will not be able to speak definitively on the subject for several more decades. His concepts of structure, tension, release, and harmony are never very far from me when I write. Persichetti’s band compositions did more to lift his recognition than anything else he wrote because so many band directors were hungry for new works. I remember playing his music for the first time as a student. It was so vital and fresh that people were drawn to it and wanted to hear more. (January 2002)

James Barnes

After studying composition and music theory at the University of Kansas, James Barnes had a long teaching career at the school. He has twice received the ABA Ostwald Award.

How would you program the perfect band concert?

First of all, the concert would be shorter than most I have sat through lately. Richard Bowles, retired Director of Bands at the University of Florida, gave me a great piece of advice about programming: set the program just the way you want it, then eliminate two of the pieces and shorten the concert. I have been to few band concerts that were too short. Fritz Reiner said that the perfect program includes a piece that you believe in, such as a new work or an older work that should be played more often; a piece that the ensemble enjoys; and a piece the audience wants to hear. This is excellent advice.

I regret that effective programming is quickly becoming a lost art among wind ensembles. It is an effort to sit through three or four college band concerts at a CBDNA convention. Poor programming is the reason that there are more people in the band that in the audience at many college band concerts. What a travesty. While I do not advocate a return to the concerts of 100 years ago, I do suggest that bands learn a wider variety of musical styles so students can play a broader scope of repertoire. A concert should include some music that the audience will enjoy. Symphony orchestras are careful to do this because they sell tickets to stay in business.

In my 25 years of conducting college bands, every program we played included at least one new piece, one band classic, almost always a featured soloist, and one good transcription. The band never played a concert without at least one march, even if only as an encore. Audiences will sit through anything if they know a march is coming later. I used to follow a contemporary work with a Sousa march as a sort of apology. The march is the only genre of music in which bands have a superior repertoire to any other ensemble. (November 2002)

William Schuman

In additional to his distinguished composing career, William Schuman served as president of the Juilliard School and the first president of Lincoln Center. He won the inaugural Pulitzer Prize for Music in 1943.

His Compositional Style

The most important element is form. I do not have form in mind before I write, a priori. Form is what happens next. What happens next must seem inevitable and at the same time it must be fresh. With Mozart, for example, when we just expect a plain recapitulation, he often gives us another development section. The form emerges as the material emerges. One section grows out of another, not in a preconceived way but in a natural way, just as the characters in a novel sometimes develop in the most logical way and other times, we feel the author has imposed his view of the way the characters developed.

Similarly, in music, the composer invents musical characters, such as a phrase, harmony, rhythm, orchestral device, timber, texture, indeed all the elements; these things take on a life of their own. What is required of a composer, is that when the work is finished, all of these combined things be brought to fruition in a way that makes unified sense.

Getting Started

When you ask me how I start a work, I can give you an example. I am working on a piece now that is exceedingly difficult. I set myself the goal of writing a duet for violin, which I have never done before. I was commissioned to do anything for clarinet: a concerto, a chamber work, anything. I suddenly fell in love with the idea of writing for these two instruments. Harmony is completely out except for implied harmony between the two instruments or when the violin uses double stops. In a sense there is implied harmony, but obviously, harmony is of very little use in that kind of composition.

Everything else has to be there: how to exploit the highs and lows in the instruments, or what contrast there will be. For example, if you just start off and go all over the place with the clarinet, you have not saved yourself. If you start in the chalumeau register, have dark colorings, have little movement, and the violin does something above, you have room to go someplace. I am purposely using an example with two instruments because with those two instruments, there are all the opportunities that exist with a symphony orchestra, only reduced to an absurdly simple level.

I do not know what I think of first when approaching a composition, but the single most thing to think of is the aural ambiance. This is only to say, what mood is this music trying to create? Is it an introduction? If so, what is it trying to introduce? In New England Triptych there is an introduction to the first movement that leads into a fast section. I wrote the fast section first, then realized that it needed an introduction and wrote the introduction. I usually write chronologically, but in that work I didn’t.

A composer should write with certainty. If the opening leaves the listener not knowing if the work is fast or slow, agitated or calm, or loud or soft, there is confusion. All music must be certain as to the atmosphere it creates. To me, that is the most important thing in composing. In the creative process for orchestral work, I might think of a theme or an instrumental combination, such as a brass choir or a brass choir with violins coming in above the brass, or I might start with the cellos above the violins. The emotion or feeling a composer tries to create is the essence of this aural ambiance.

I think in emotional terms and technical terms at the same time. I can give you no more of an answer than this. The reason I cannot give you a more definitive answer is that I cannot give myself a more definite answer. I only know that you are no better a composer than you are critic. The music that you issue is the music that does not go in the ash can. The more music you throw in the ash can, the more selective you are. The more selective you are, the stronger a composer you will be. (April 1986, published November 1993)

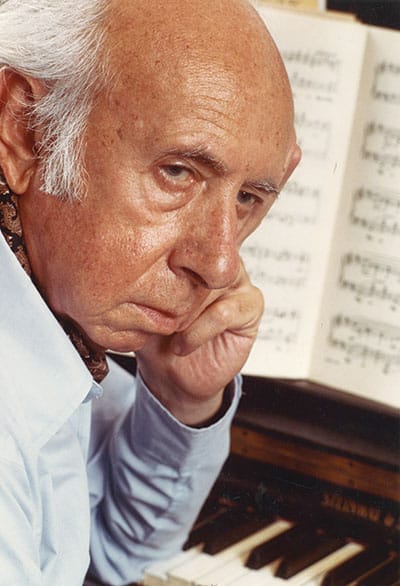

Morton Gould

Morton Gould’s prolific and admired works include Broadway scores, commissions by symphonic orchestras, and various musical honors.

When Mills Music took me on as a composer in the 30s and suggested that I write some band music, I must confess I turned up my nose at the idea. I said, “Why do I want to write for band? I’m having enough problems with the professional orchestras.” I was very young and was a little more volatile than I am now. I’d gotten into hassles as a young conductor, conducting men older than I was, arguing with them about intonation and tuning and so on – violent confrontations. And so I thought: I’m having enough problems right here, why should I have to deal with music for kids? But the general manager of Mills Music, Max Stark, convinced me to do part of a concert and introduce my Cowboy Rhapsody. I remember saying to Max Stark: “Max, why am I doing this?” And he said, “You’re going to be surprised, very surprised.”

I remember all this so clearly. I walked into Hill Auditorium and met Bill Revelli and he said, “Why don’t you go and sit in the auditorium. Let me warm the band up for you.” I sat down very skeptically and saw this huge band tuning up, which impressed me because they were obviously tuning. There was no horsing around about that. I had never heard a professional orchestra tune that way. Then Bill gave a down beat and this beautiful sound came out – a Wagner transcription. I fell right out of my chair because I had heard something that was equivalent in quality to the finest professional orchestras of that time. Within one minute, I was a convert. I realized what an important medium this was. I felt that I, the so-called serious or symphonic composer, wanted to be part of this. It stimulated me. From then on, as you know, I wrote a considerable amount of music in both large and small forms, and many of my orchestral works were transcribed by other people for band. Yes, I wrote for band, and to this day I find it a fascinating medium. (October 1978)

Clare Grundman

Clare Grundman studied composition with Paul Hindemith and also earned degrees at Ohio State University. In addition to his original compositions and arrangements for band, he wrote for Broadway, films, radio and television.

Advice for High School Students

To be good in any field, whether it may be art, literature, sports, or any else, you’ve got to start with the basics. For a composer, the basics are an understanding of harmony, theory, and counterpoint. Later, if you want to get away from the traditional framework, you can. But at least you have something to start writing from.

Then if you’re going to write for a certain medium, such as the band, you should really get into that medium. It’s hard for people to write or arrange for band when they haven’t played in it and don’t really know how it sounds. If they’ve only heard the band from the audience, sitting up front, they never learn what can and can’t be done, and exactly what combination of instruments sounds good or bad. Probably the best composition lesson is to listen to the colors and sounds of music while you’re sitting right in the middle of it all. (September 1982)

Jennifer Higdon

Jennifer Higdon has received commissions by major symphony orchestras and soloists. Her most popular work, blue cathedral, has been performed more than 400 orchestras around the world.

I first wrote for flute because my friends were flutists, and we played in flute choirs together. They were the people who were asking me for music. I am so thankful that I played an instrument. When composing, I seriously consider what it is like to be on the other side of the music stand and what performers are experiencing as they look at the page. My earliest successes were because flute players were so enthusiastic about new music.

In June 2002, the Philadelphia Orchestra premiered my Concerto for Orchestra, which had been commissioned in 1998, to celebrate the orchestra’s centennial in the newly built Kimmel Center. My life started to change almost overnight after that premiere, and I only played flute for a couple more years. I could tell that composition was the direction my life was supposed to go, and it felt like putting on an extremely comfortable pair of shoes. I was never aware that composers could have one concert that would actually change their lives. I had heard of that with conductors and performers, but never with a composer. It was completely terrifying. (November 2017)