When I began writing for band as a high school student in the mid-1980s, computer notation software was not available to me. The work was done with pencil and paper at the piano, and when the score was complete, the parts had to be transposed and copied by hand. It was a time-consuming process that required specialized knowledge, and students who engaged in the activity were rare.

Today, free notation programs have fueled a dramatic increase in the number of students engaging in composition and arranging, but many of the charts they produce show a lack of familiarity with basic concepts of notation and scoring. As a veteran arranger and teacher of arranging and orchestration, I offer these tips to help guide students who show interest in writing for band.

1. In eighth-note-oriented music, show downbeats, especially beat three.

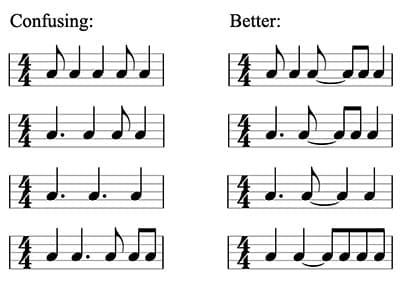

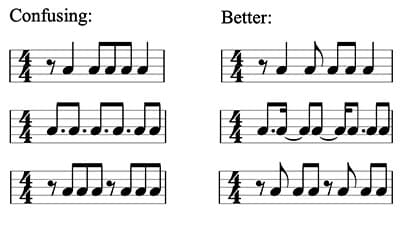

Student arrangers are often unfamiliar with standard notation practices and write rhythms in ways that are technically correct but potentially confusing to performers. To avoid confusion, always maintain a visual subdivision of each measure into two equal halves.

In general, the beaming of eighth notes should reflect the time signature. When used, beams should cross whole beats, not half beats. I also avoid beaming three eighth notes together in common time, as they are sometimes confused with eighth-note triplets.

2. Always use as few accidentals as possible.

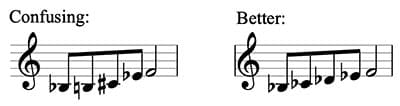

When writing passages including chromatic motives, measures can quickly become cluttered with excessive accidentals. The readability of the parts can be improved by using sharps for ascending chromatic passages and flats when descending. When entering non-diatonic pitches into a notation program using a MIDI device, the software’s defaults sometimes result in a poor accidental choice. It is important to proofread melodic lines and enharmonically flip the accidentals to follow the sharps-ascending/flats-descending rule. Notice that doing the opposite requires twice as many accidentals.

Similarly, the readability of non-diatonic passages can be improved by presenting them in a diatonic context. In the example below, the first measure’s mixture of accidentals seems random and will be difficult to read. The second measure’s consistent use of flats clearly presents the motive as the first five notes of the Bb Phygian mode and will be much easier to read correctly on the first pass.

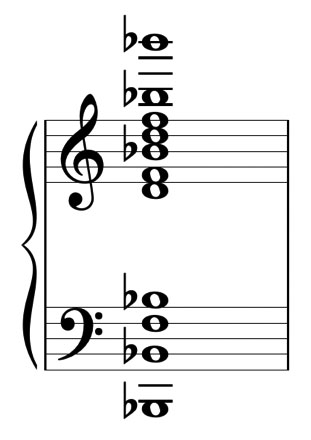

3. Use the overtone series as a blueprint for chord voicing.

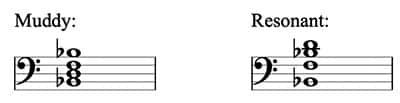

The overtone series is also known as the chord of nature. It is naturally resonant, and good results follow when your scoring copies the intervallic relationships you find there. Consider the overtones sounding above a Bb fundamental (up through the 8th partial).

Notice first that the lowest pitches are widely spaced. My general practice when scoring in the low register is to keep a minimum distance of a 5th above the bass note. Student arrangers frequently default to root position triads, but close stacked thirds in the low register will sound muddy. Inverting the upper voices creates space and sounds more resonant.

Second, notice that the chord spelled by the overtone series contains four roots and two fifths, but a single third and seventh. Scoring a triad or seventh chord for the full band requires extensive doubling, but in like proportion to the overtone series, with the third and seventh doubled sparingly (or not at all).

Bb major triad scored for full band (concert pitch)

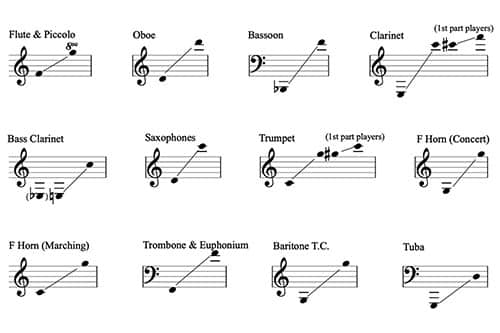

4. Score instruments in practical/comfortable ranges.

Notation programs will highlight notes that are out of bounds, but their defaults typically encompass the full possible range of each instrument. Nearly all instruments experience compromised tone quality, difficulty of dynamic control, or challenging intonation at the extremes of their ranges, and these problems are magnified with student or amateur ensembles. With my arranging students, I advise keeping all instruments within narrower practical ranges, keeping in mind that the ranges diminish further for young ensembles.

It is important to emphasize that these are written ranges, not sounding, and it is advisable to work with the notation program in its transposed view. Many students create scoring that appears (to them) workable in concert pitch, only to flip to transposed view at the end of the project and discover that many pitches are outside an instrument’s written practical range.

Practical wind ranges (written pitch)

5. Score the melody prominently.

When I critique concert bands, I frequently comment that the melody is covered by the accompanying voices. Often, this is the result of poor balancing by the ensemble, but in some cases, a glance at the score reveals that the accompanying voices are too loudly or thickly orchestrated. This is sometimes a problem in music composed for young band, where tutti writing predominates in an effort to maximize student engagement. When writing tutti passages, it usually won’t work to write the melody in a single instrumental voice (with the possible exception of the trumpets). However, a thinly scored melody becomes possible if the accompanying voices are also reduced.

Though young writers typically default to writing the melody in the soprano voice, timbrel variety can be achieved through scoring melodic material in the alto, tenor, or bass voices. When doing so, the writer must be careful not to mask the melody. Either the accompaniment must be in a different range from the melody, or the melody must be scored in a unique timbre that will not blend with a harmonic accompaniment in the same range.

While much of the success of an arrangement or composition depends upon other concepts such as formal structure, key selection, timbrel/textural decisions, idiomatic use of instruments, etc., adherence to these five tips can help to ensure that even basic arrangements by fledgling arrangers will “work” right out of the box.