Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in the November 1984 issue of The Instrumentalist.

There is probably no more striking example of the enhanced opportunities open to the instrumentalist and composer in today’s music world than the case of the Marsalis family.

By now it is all but impossible to be unaware of the unique achievements of Wynton Marsalis. For the past two years he has been the most publicized young newcomer in music. Feature articles in national magazines, TV exposure, and concerts in the country’s most prestigious halls, have played their part; but much of this might never have happened were it not for the dual nature of his career.

Last spring the trumpet virtuoso, born October 18, 1961, became the first musician in the history of the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences to win two Grammys simultaneously for a classical recording and a jazz album. The latter featured his elder brother Branford (born August 26, 1960), a saxophonist who, in the opinion of some observers (including Wynton himself), is even more talented than Wynton.

In every article about these two virtuosic performers, the name of their father has been mentioned; yet the full story of Ellis Marsalis, a New Orleans legend in his own right as pianist, composer, and educator has never been told.

Ellis Marsalis

Ellis Marsalis

The Marsalis Saga

The background of Ellis Marsalis differed from that of his children on three levels. One dynamic is the radical improvement in the music education system; a second, closely related, is the gradual change in the attitude toward jazz, from ignorance or rejection to reluctant acceptance to affirmative action. The third is the impact of the social revolution in the 1960s.

Ironically, Ellis Marsalis, born and raised during the era of rigid segregation, today enjoys a prestigious career in which integration plays a significant part. For the past decade he has been teaching at the New Orleans Center for Creative Arts. Created as the product of a federal grant, the Center deals with five disciplines: music, visual arts, theater, creative writing, and dance. “I was hired,” says Ellis Marsalis, “to round out the faculty from the jazz point of view. The entrance qualification is simply based on auditions; there has never been any other way to get in. Lately, the word has gotten around about the high level of training; as a result a number of private school students are enrolling.”

Contrary to a popular misconception fostered by certain generalizations in the media, the extraordinary successes and fame of Wynton Marsalis and brother Branford cannot be attributed simply to the help of their father. True, they both attended the Center and were offered guidance by him, but that is only part of the story. Before filling in the gaps it is necessary to examine Ellis Marsalis’ own training and background.

Ellis’ Youth

He was born in New Orleans, where his father was the proprietor of a motel. “My father was always in business; he was self-supporting, and never had to take a porter’s job. My mother never had to worry much about finances, though at one time she did go to work as a maid for a white doctor, and I suspect that a lot of the things she observed in that family influenced how she wanted to raise her children. She sent my sister and me to Xavier University Junior School of Music. My mother thought that this was what people did with their children – music and dance lessons; this was what a cultured family did.”

The university was run by the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament. Their attitudes typified the. musical stance at virtually every university in those days. As Ellis Marsalis puts it, “Every European composer had a halo around his head and could do no wrong. There was no other kind of music. There was absolutely no recognition of jazz – not even of its existence, let alone its validity as an art form.”

Nevertheless, when he began to raise a family, he did not place any emphasis on classical music. In spite of the attempts to inculcate an interest at Xavier, he says, “My knowledge in that area was almost nil, except for a few things I had listened to for my own enjoyment.” (Nevertheless, after extensive piano and clarinet studies, he took up cello at Xavier and continued at the University of Southwestern Louisiana, where he played it in the symphony from 1964–66.) “Basically,” the senior Marsalis insists, “I was a jazz player from day one.”

Big Band Bebop

Day one came about when he began listening to a local radio program. “The bebop thing had just taken over, and I heard Dizzy Gillespie’s band, also Jackie Cain and Roy Kral singing with Charlie Ventura’s band. We all knew about these things even back in high school. Then I heard that Dizzy was bringing his big band to town, and I couldn’t wait to see him.”

This was 1949; Ellis Marsalis, 13 years old, had never heard anything like the live sound of that seminal orchestra. Later he heard Norman Granz’ Jazz at the Philharmonic touring group, Nat King Cole, and others who would shape his musical direction, though for a long while he learned nothing technically, because there was no place to turn for jazz education.

“I finally learned from a friend, Harold Battiste, who was a senior at Xavier. We were in the band room one day and he said, ‘Hey, man, play me a C7 chord.’ I said, ‘What is that?’ So he went to the blackboard and constructed some chord symbols. That was the first formal jazz lesson I ever had.”

Marsalis continued to learn, “patchwork style” as he calls it, mostly empirically on some of his early jobs. In due course he was able to live a double life as performer and teacher.

“I played at a jazz club here for about a year and a half, which is some kind of record for New Orleans, and during that period I was teaching parttime at a small university. You can imagine the kind of money they paid, particularly part time.”

Despite his continuing work as an educator, Marsalis never stopped playing. “Some people would say ‘Yeah, I’m trying to earn some extra money.’ Well, playing was an important part of my financial balance, to keep the family going. To me, none of it was ever extra – if you know anything about the salaries that are paid for teaching school, you realize that nothing is really extra. Perhaps I could have made about the same amount of money if I’d just been out hustling gigs, but the point is, there’s no security in that, and it would have driven my wife crazy.’’

Ellis the Educator

Marsalis had been married for two or three years when he began teaching in 1963. “I was supposed to be a band director, but the political system that engulfed the school was so bad, I ended up teaching seventh and eighth grade science classes, and some general music; and at this time we were right in the throes of the desegregation crisis.’’

Disillusioned, he quit and, with his wife, moved bag and baggage to the small town of Beaux Bridge, Louisiana, where he was a band director for two years.

“That was Cajun country. My mother was raised in that kind of environment, so I was familiar with the Creole language. I learned a lot from that experience, but after two years my wife and I felt we had to get back to New Orleans.”

Marsalis started working at the Playboy Club. “It was a solid six-nights-a-week gig, but it wasn’t advancing me musically. I was still a little idealistic; I’d run down the street between sets and catch Buddy Rich’s band at Al Hirt’s club, and later Duke Ellington. I’d played jobs accompanying some of the acts at Al’s place, and I knew Al’s partner, Dan Levy, pretty well.”

Quitting the Playboy Club, he went through a fallow period. “I wasn’t doing much of anything – I was working at my daddy’s place – kind of disillusioned. Then one night I ran into Dan Levy, told him I wasn’t doing anything, and he mentioned it to Pee Wee Spitelara, Al’s clarinetist. Pee Wee called and asked if I’d like to join the band. I said ‘Yeah!’ and that was sort of my ticket back into music. I stayed with Al three-and-a-half years.”

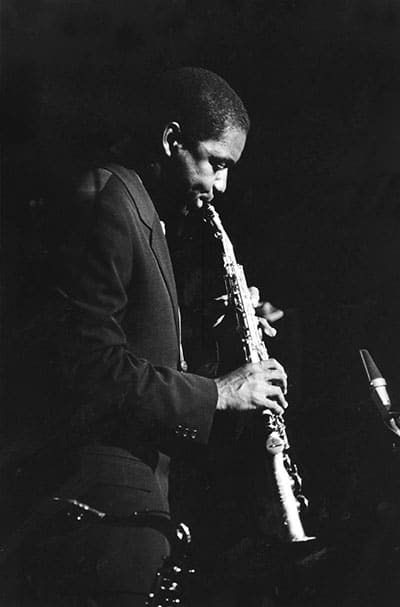

Wynton Marsalis

Wynton’s First Horn

During this time, Marsalis would sometimes bring Wynton and Branford along to rehearsals at the Bourbon Street club. As Hirt recalls it, “Wynton would start banging around on the piano. I finally said, ‘Hey, let’s get that kid away from there. I’ll give him this trumpet.’”

That he allowed the gift horn to remain in its case for six years is a curious aspect of the Wynton Marsalis story. His father, though, has a simple explanation regarding the long gap. “Wynton was just busy being a kid! He was playing baseball, little league football, and he really loved basketball.

“Branford wanted to go to an all-boys Catholic school, and his mother didn’t want him to go alone, so she said: ‘Wynton, why don’t you do your eighth grade year there?’ Wynton auditioned for the band, but he didn’t make the big group – they put him in the second band.’’

“I Really Need a Teacher’’

Then came an incident that was to be crucial in the youngster’s life, one that illustrated how important the competitive instinct was in him. “There was a kid about the same age, studying with the same man who later taught Wynton. The kid could really play rings around Wynton, whose ego was bruised by this. So then my son got serious and said to me, ‘Oh, man, I really need a teacher.’”

Wynton Marsalis

Ellis investigated extensively. The first teacher he found who set Wynton on the right track was John Longo, with whom he studied for a year or two. In his sophomore year Wynton left and began taking classes at the New Orleans Center for Creative Arts.

It is difficult to determine which musical idiom first engaged the young trumpeter’s serious attention. At one point he and Branford played in a rock and roll band; they learned the repertoire of groups such as Earth, Wind & Fire, becoming one of the few bands in the city capable of dealing with this genre.

Wynton’s training with Longo was classical, his father says, “only in the sense that if you study an instrument formally, you use the standard method books. Although Longo was exceptionally well-trained, there was no study of the classics systematically – no awareness of the Baroque, Renaissance, and other periods. Wynton’s study of classical music really began when he started at the Center.”

Wynton’s introduction to jazz also came about gradually. His father worked with him on the concept of improvisation, but in the early years – sixth and seventh grades – he displayed indifference when listening to a Miles Davis record. “But I had a lot of recordings, and eventually he really began to listen to all the greats like Clifford Brown, Dizzy, Miles – he would even learn to play a Miles Davis solo, note for note, off the record. But all the while there was ongoing classical training, so that his development was well-balanced.”

What the records of the jazz giants did for Wynton in that area, a tape of Maurice André accomplished for him when, at the age of 13, he now says, “All the jazz musicians were in awe of the classical guys, so I decided to look into it.” He practiced continuously, though today he resents the stories that describe him as classically trained. “I’m just a cat who started playing the trumpet, and who happened to like classical music,” he says. “Training is training, no matter where it leads you; you keep practicing scales and exercises, and you use this experience to play anything you want.”

All this happened around the time Wynton, in addition to attending a regular public school, began to double up at the Center for Creative Arts. He made such rapid headway that at 14 he played the Haydn Trumpet Concerto with the New Orleans Symphony.

“All I did was think about music, practice it, play it. It’s a constant process of investigation, refining, absorbing, eliminating, and trying to understand, whether it’s Maurice André or Clifford Brown or Charlie Parker.”

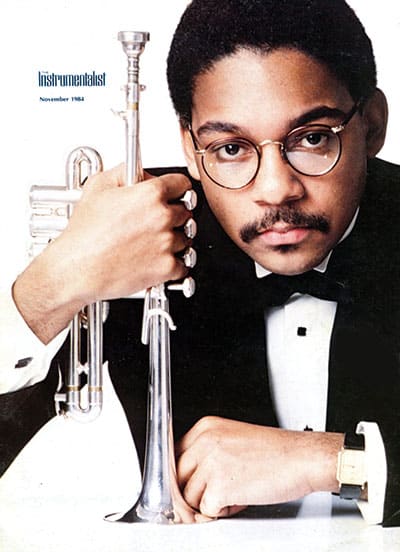

Branford – Like Father, Like Son

Branford Marsalis was less eclectic than his brother. “Piano was my first instrument – like father, like son,” he recalls. “Then I took up clarinet, but realized I didn’t like it. I didn’t want to sit in a chair for the rest of my life playing music that was already written. So I had my dad get me an alto saxophone for Christmas.”

Branford Marsalis

Branford left home in 1978 to continue his studies at Southern University in Baton Rouge. While there, he switched to tenor sax and found role models in the records of John Coltrane, Sonny Rollins, and Joe Henderson. Then in 1979, Wynton, a few months before his 18th birthday, left for New York, where he studied at Juilliard, played in a pit band for a Broadway show, and worked with the Brooklyn Philharmonia.

Around this time, despite his modest disavowal of classical credentials, Ellis Marsalis was making headway on significant levels. He performed Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue with the New Orleans Philharmonic Symphony, and in 1980 premiered his own composition, Ballad for Jazz Trio and Symphony Orchestra, for which his own small group teamed with the Symphony. At the same time his jazz career continued apace: between 1976 and 1981 he worked in a club at the Hyatt Regency where his trio was teamed at various times with such veterans as Clark Terry, Red Norvo, Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis, and Harry “Sweets” Edison.

More by accident than design, all three Marsalises put in time with the legendary drummer Art Blakey and his Jazz Messengers. Wynton, not long after his arrival in New York, sat in with the band and was promptly offered a job. Before leaving Blakey in 1981 he had become the group’s musical director.

Branford, who transferred to Boston’s Berklee College of Music late in 1979, accepted an offer during his summer vacation to go on the road with Blakey, who at that point had two trumpeters, Wynton Marsalis, and the Soviet jazzman Valery Ponomarev. Completing the family cycle, Ellis Marsalis worked with Blakey in Houston in 1981.

Recent Triumphs

The story of the past two or three years is an often–told tale. Branford, after returning to Berklee for a while, went on tour with Clark Terry’s big band, eventually joined Wynton’s Quintet, and recently, in addition to leading a small group of his own, attracted the attention of Miles Davis, who used him on his latest album, Decoy. Both Wynton and Branford also toured with Herbie Hancock’s VSOP group, an experience they found particularly stimulating. (“I was never nervous,” says Wynton, “because they didn’t treat me like some young kid – they treated me with respect.”)

Branford Marsalis

Wynton’s contract with Columbia Records was without precedent in the history of the recording industry. He was guaranteed albums with his own jazz group and with a symphony orchestra. As a consequence, this year he won Grammy awards both for his album of Haydn, Mozart, and Hummel Concertos for Trumpet and Orchestra and for his quintet’s Think of One. Again rounding out the familial picture, all three artists have been heard in one side of an album, Fathers & Sons. The other side of the LP featured two saxophonists, Von Freeman and his son, Chico Freeman.

Asked to explain the prodigious nature of his sons’ success, Ellis Marsalis replied: “I think Wynton would have succeeded at whatever career he might have decided upon. He was always a good student. Also, at the Center, where Wynton and Branford both studied, we have a unique situation. If someone is mature enough at an early enough age, and if he doesn’t mind practicing and developing a thorough discipline, he can go in any direction he chooses, be it classical, jazz, or what have you.”

“What,” I asked, “were the major differences between Branford and Wynton as individuals?”

“I always thought that Branford had the most natural ability. But he was a lot more like me, and Wynton’s like his mom. It’s a hard thing to explain, what makes one person determined to study, as opposed to someone who says, well, I’ll do that later. The thing that motivated Wynton, of course, was that kid I told you about who outplayed him. Wynton in any case has more natural leader characteristics than Branford.”

While he watches his children going from one triumph to another, Ellis keeps a firm hold on his own career. “I quit a regular playing gig a while back, because it was too hard to work five or six nights a week and teach too. But I still have a regular gig, every Monday at a place called Tyler’s, in a duo with a guitar player.”

As Ellis confirms, the Marsalis family saga is far from complete. “My third son, who’s 20, is a student at New York University, majoring in history. He’s Ellis III – I’m a junior. My fourth son, Delfeayo, is a student at Berklee, in audio engineering. He produced my last album. Our fifth son, Mboya, is autistic; he’s 13. The last one is Jason, who’s seven, and probably more talented than all of them. Right now he’s playing drums and violin in a Suzuki class. He has perfect pitch.

“We were riding down the street the other day and I had a tape on of Tommy Flanagan’s piano album dedicated to John Coltrane. Delfeayo said, ‘Who is that?’ I said, ‘That’s Flanagan.’ Then he asked, ‘What’s that he’s playing?’ And Jason piped up and told him: ‘It’s Giant Steps! This was right in the middle of an ad lib solo! He listens all the time and can tell you about all the great drum solos by Philly Joe Jones, Elvin Jones, and the rest. People ask me, ‘Do you make him do this?’ and I tell them, ‘Hey, have you ever tried to make a seven year old do anything?’”

“You must be terribly proud of them all,” I commented.

“Oh, indeed I am.’’

More proud, I suspect, than surprised.