Most of us in the instrumental music education profession attended a college or university that required study of all woodwind, brass, percussion, and string instruments towards teacher certification. In most cases, there was also the requirement to demonstrate a prescribed level of piano proficiency. While the majority of us specialize in one or two instruments, possessing an advanced level of proficiency on more instruments is rare. The goal of most of these pedagogy courses is to give music education majors the tools necessary to teach their students at the beginning and intermediate levels on each instrument. A result of these courses may also provide confidence to the teacher in the large ensemble by affording them the ability to understand and relate to the mechanics and tendencies of each instrument within.

Stephen Benham is Professor of Music Education at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. During his K-12 experiences in Michigan, Oregon, and New York, he was a strings teacher, orchestra director, and band director. Drawing on his experience across multiple instrumental areas, Benham answers some of the most pressing questions that may be on the minds of band directors who may soon find themselves in front of a group of students holding string instruments.

There has been a documented shortage of string teachers for at least the past 15 years. In part this is because of program growth around the country, but also because there is an insufficient number of string majors graduating from music education teacher preparation programs. I believe that the trend will continue at least for the next decade – if not longer. The American String Teachers Association has tracked this for some time and will continue to do so; in addition, there are other national efforts under development to help recruit a greater number of players.

What advice would you offer a recent wind or percussion graduate for developing confidence teaching strings?

I would say that anyone, anywhere in the country, should expect to teach music outside of their major area, such as a wind or percussion specialist teaching choir or strings, or a vocalist teaching band. That is the trend nationally. In turn, this should weigh on college choices by future music majors. Is the university you are looking for someplace where you can be trained by specialists in each of the major areas (band, choral, orchestra, and general music)? Being an excellent musician is key to success in any field. Know a wide range of music. Work hard on your ear training and aural skills. Attend as many clinic sessions on topics outside of your major area as possible at professional development conferences.

What are some direct correlations from wind performance that transfer to strings?

The principles of acoustics are the same between strings and winds: We are looking at creating and controlling vibration of air molecules. In this regard, the bow correlates highly to the breath/airstream. In strings, we really understand four basic principles of tone production from the perspective of bowing: weight, angle, speed, and placement (WASP).

Weight

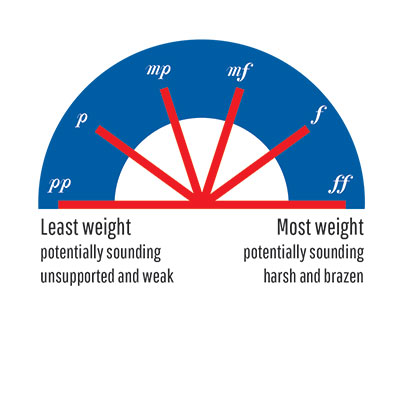

In general, the greater the weight, the louder the sound (think about more breath support for larger volume). There is a concern that using less weight, might produce a potentially weak and unsupported sound. In contrast, using more weight may produce a potentially harsh and brash sound. For bow weight, consider the following diagram:

Angle

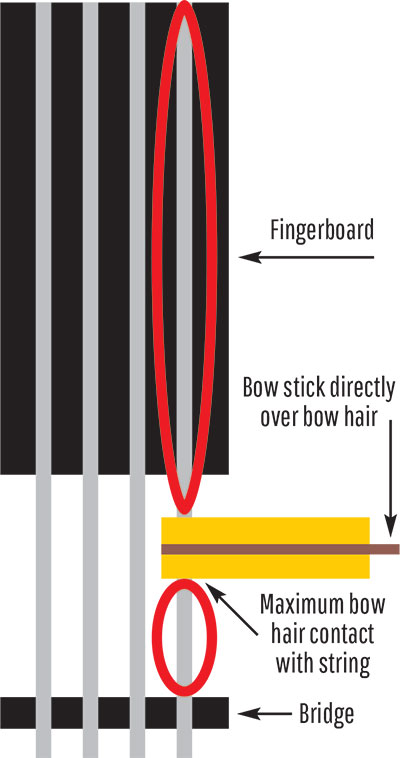

If the hair of the bow is completely flat on the string, there is much less string available to vibrate, making the overall sound less full. In the diagram below, the red circle shows the amount of string available to vibrate with most of the bow hair making contact:

To achieve the best sound, the angle of the bow stick should be slightly adjusted towards the fingerboard. For violins and violas, this would mean angling the bow stick away from the performer’s face, and for cellos and basses it would require the performer to angle the bow stick toward the face. By doing this, the hair begins to bunch up underneath the bow stick, creating the opportunity for more friction with the string. With less bow hair on the string, more of the string is able to vibrate, thus creating a richer and fuller sound (larger red circle):

.jpg)

In many ways, a wind performer can relate the concept of angle similar to a beginning flute player trying to produce a sound over the tone hole. In many respects having the angle of air flow over the tone hole at a sweet spot takes some time and patience. Once this angle is found, it is difficult for the performer to revert to anything less. For string players, the process can be equally satisfying.

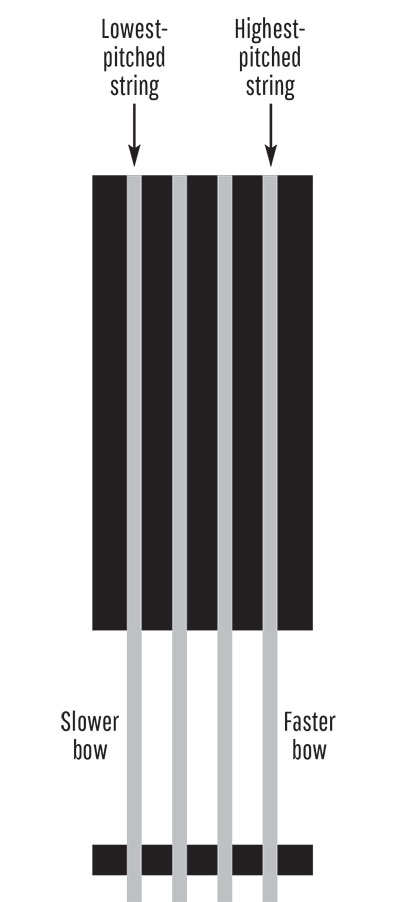

Speed

One common misconception that developing string teachers encounter is the term “more bow.” Often, this is interpreted as using a faster bow stroke, similar to how a band director might ask students to use more air. Although it is true that wind payers should take big breaths to secure a well-supported sound, it is the speed – or management – of the air that is ultimately responsible for a well-supported sound.

To assist in understanding air management, consider the following scenario. A trumpet player asked to play a C5 should take a big breath and play the note with fast air right from the start, as any hesitance leads to tightness, causing a poor start to the note. A trumpet player asked to play a C4 should take a similarly big breath but play the lower note with a slower airstream. Bow usage should be approached in the same manner.

Placement

Another general rule of thumb is that placement of the bow can affect dynamics and timbre. Regarding dynamics, the distance between the fingerboard and the bridge can be thought of as having six different lanes or bowing channels. As one approaches the bridge from the fingerboard, the dynamics increase in intensity. Similarly, the timbre grows from darker, covered, and potentially dull to more focused, intense, and potentially shrill:

.jpg)

These foundations should be followed to develop a basic understanding of the four principles of bow usage. Reed players may find similar attributes in regard to how much mouthpiece to take in on higher- or lower-pitched passages, and brass players might adjust their embouchures for passages that require playing in different registers. As is the case with woodwind and brass players, there are many combinations of bow weight, angle, speed, and placement that can develop a wide array of colors for the string performer.

There are some special effects in string playing that take advantage of some of the acoustical effects that result from not having a centered sound. For example, sul ponticello is is created by placing less than the usual amount of weight on the bow, moving the bow too quickly, and placing the bow too close to the bridge, resulting in a glassy, unfocused, airy sound. Sul tasto is created by having the bow move more lightly and quickly across the strings than would produce a focused sound, resulting in a more ethereal, covered, and breathy sound.

Are there any direct correlations from percussion performance that transfer to strings?

Striking a drum or keyboard instrument with a stick or mallet is quite similar to the kinesthetics involved in playing with the bow. There is an anticipation of the motion, an execution of the motion, and a rebound. I love watching professional timpanists and percussionists because they prep for the sound initiation in a way that is visible and anticipates the laws of motion. For example, a timpanist does not merely smack the head of the timpani to achieve a good sound. Rather, the timpanist draws the sound from the head by using the entire arm mechanism in a relaxed manner; from preparation to execution and beyond, the entire motion is more of drawing out the sound from the head. The string player also has to achieve a similar relaxed preparation with the arm mechanism, which usually includes the upper body to assist and then allow the bow to be drawn across the string with enough weight to initiate the string to vibrate, but not so much that the vibration would be compromised.

For string players, there is an additional correlation with off-the-string bowings, in which the bow rebounds from the string, rather than staying constantly on the string. When you watch timpanists – in particular – play repeated notes, you see this relaxed control and response of the fingers-hand-wrist-forearm-

Another analogy that relates well from percussion to strings is comparing bow placement to stick placement. Just as a timpanist will need to determine how far from the rim to strike the head, a string player will need to find where the best sound is produced on each string.

For students who has been trained to become a band director, which composers for strings would you recommend?

There are excellent composers for school strings right now. Bob Phillips, Soon Hee Newbold, Richard Meyer, Sandra Dackow, Brian Balmages, and Mark Williams all come to mind. In addition, there is an outstanding repertoire going back hundreds of years that is playable by school string players. The Teaching Music Through Performance in Orchestra series published by GIA, which also has a much more extensive band series by the same name, is a great starting point.

How should directors assign bowings to parts?

There are many options for how parts may be bowed, and what you do for a younger orchestra will be different from what a professional orchestra does in the same way that you might use different breath or phrasing markings for beginning band students and top high school wind ensemble. Talk to the private teachers in your area, borrow marked parts from another school, or talk to a nearby university orchestra director. There are also good bowing suggestions in books by James Kjelland (Orchestral Bowings: Style and Routines, published by Kjos), Elizabeth Green (Orchestral Bowings and Routines, published by ASTA), and Marvin Rabin (Guide to Orchestral Bowings Through Musical Styles, published by the University of Wisconsin).

Are there any differences in conducting a band versus and orchestra?

Although rehearsal preparation is going to be similar, diagnosing performance problems can be significantly different. So much of tone production for the string player is external and therefore easy to identify and understand. Small corrections can easily be demonstrated, such as the difference between starting at the tip of the bow, where the weight is lighter versus the middle or frog of the bow, where the weight becomes successively heavier. String players also seem to have a greater range of colors at their disposal because of the wide number of options that can be used to create tone. Even descriptions of bowing technique and articulation fill entire dictionaries, which is something that is not the same for the wind player. Diagnosing tonal production problems for wind players is much more complex as it is virtually impossible to see where the tongue is making contact with the reed or mouthpiece, what part and how much of the tongue is being used, the shape of the inside of the oral cavity, and how much air (and in what type of column) is being used to create the sound. So, many analogies can be made using strings that could be helpful for wind players.

For string players, there is a distinction between the name of the technique that is used to accomplish an articulation and the actual articulation style, itself. For example, a staccato articulation can be produced with a martelé, détaché, spiccato, or sautillé bow stroke. These technical elements often relate to performance practice and also evolved in relation to changes in the string instruments over time. The Green, Rabin, and Kjelland materials mentioned above are excellent resources. There is also the Dictionary of Bowing and Pizzicato Terms by Joel Berman, Barbara Jackson, and Kenneth Sarch that provides excellent research on basically all standard (and quite a few lesser-known and rarely used) terms and technique in multiple languages in orchestral repertoire.

Although teaching outside of one’s primary area can produce some degree of anxiety, it is important to remember that the relationship between woodwinds, brass, percussion, and strings is closer than one may initially think. Afterall, relating to areas that are outside our comfort zone is something that instrumental music educators do all the time. A person who is primarily a brass player must find a way to relate to woodwind players about producing an initial sound on their instrument. The embouchure required from a brass player needs to be demonstrated in such a way that allows for the center of the lips to vibrate, whereas reed players need to be concerned about getting the tip of the reed to vibrate freely. The vibration of the reed is similar to the vibration produced by the aperture for a brass player.

It is anticipated that most of the anxiety band directors who find themselves teaching strings comes from the visual aspect of how the instrument is played. In many regards, band directors who teach strings have a greater chance of success due primarily to the external nature of performing on string instruments, versus the internal execution required of woodwind and brass players. Regardless, instrumentalists can relate what they already know to concepts that they are less familiar and have measurable success. Like most things in our profession, this takes practice.