“The spirit of music that unites us here is not an illusion, but rather a revelation. The power of music lies in the fact that it reveals to us beauties which we cannot find in any other sphere, and the comprehension of these beauties is not transitory, but rather a reconciliation with life itself.”

– Charles Munch’s address to the students of Tanglewood, 1954

The distinguished conductor and violinist Charles Munch, was born in Strasbourg, Alsace-Lorraine on September 26, 1891. At the time of Munch’s birth Alsace was part of the German empire and later, after World War I, became part of France in 1919.

Munch’s first musical instruction was from his father, Ernst Munch (1859-1928), who was an Alsatian organist and choral conductor. Munch took lessons from his father on violin, organ, and harmony and counterpoint. His father also taught and directed an orchestra at the Strasbourg Conservatory and allowed Charles to play in the second violin section.

As a boy, Charles met many of his father’s musical friends, including the great Hungarian conductor Arthur Nikisch, composer Vincent d’lndy and Albert Schweitzer, who was the organist for his father’s choir. Charles Munch studied violin at the Strasbourg Conservatory and received his diploma in 1912. For additional training he studied violin with two of the most admired and respected teachers of their time – Carl Flesch in Berlin and Lucien Capet at the Paris Conservatoire. Capet and Flesch were decisive influences on Munch and shaped his concept of violin playing immensely.

Munch’s rapid progress on the violin came to an abrupt halt at the outbreak of World War I. Because Strasbourg was part of the German empire, Munch was drafted into the German army, serving as a sergeant of artillery. He was gassed at Perrone and wounded at Verdun. After the end of the war, Munch returned to Alsace-Lorraine in 1919 and became a naturalized French citizen, professor of violin at the Strasbourg Conservatory, and assistant concertmaster of the Strasbourg Philharmonic Orchestra. From 1926-1933 he was concertmaster of the Leipzig Gewandhaus orchestra under Maestro Wilhelm Furtwangler, who inspired Munch to become a conductor.

Munch came to conducting rather late, at the age of 41, and made his conducting debut in Paris on November 1, 1932. His fiancée, Genevieve Maury, granddaughter of the founder of Nestlé, rented the hall and hired the Walther Staram Orchestra for her future husband’s debut. The concert received outstanding reviews from the critics, and following this success, Munch received invitations to conduct many French orchestras. He also taught conducting at the Paris Conservatoire from 1937 to 1945. Munch’s advice to his conducting students was, “If you interpret music as you feel it, with ardor and faith, with all your heart and with complete conviction, I am certain that even if the critics attack you, God will forgive you.”

During World War II and the difficult years of the German occupation of Paris (1940-1944) Munch continued to teach conducting at the conservatory and was also the conductor of the Societe des Concerts du Conservatoire de Paris, which was the finest orchestra in France. He protected members of this orchestra from the Gestapo and gave his salary to the French Resistance. For this service, he received the Legion d’Honneur from the French government after the war.

My colleague at the Oberlin Conservatory, professor of flute Michel Debost, was a young boy in Paris during the war years and recalls a touching moment he experienced at that time: “My earliest memory of the orchestra is from December 1944, when my mother took me to an orchestra concert on a Saturday morning with Charles Munch conducting. The concert started late, but Munch, who was Alsatian born, stormed onto the stage and told the audience, ‘Strasbourg has just been liberated, so we will play La Marseillaise.’ As the national anthem was performed everyone stood with tears streaming down their faces. This was a poignant moment in my life. Twenty years later when I played for Munch, I didn’t dare tell him of this memory, but I should have because it was so emotional.”

After the war Munch’s reputation as a conductor was meteoric as he received rave reviews in Israel, Prague, and Edinburgh. Charles Munch made his United States debut as a guest conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra on December 27, 1946, and in the 1947-48 season he also conducted the New York Philharmonic. Olin Downes, then the music critic of the New York Times wrote a glowing review of Munch’s conducting, praising his “masterly treatment of phrase, his exceptional range of sonorities, from the nearly inaudible pianissimo to the fortissimo . . . the complete flexibility of beat and capacity that is desirable for romantic rhetoric.”

From 1949-1962 Munch was Music Director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, where he was noted for his excellent interpretations of the French repertoire, especially Berlioz, Debussy, and Ravel. His thirteen-year tenure with the Boston Symphony turned the orchestra into the most French sounding orchestra in America, noted for extreme refinement, spontaneity, and passion.

In his 1955 book, I Am a Conductor, Munch expressed his philosophy of conducting: “. . . it is not a profession at all but a sacred calling. It takes work to make a conductor. You must work from the day you first walk through the conservatory door to the night, when, exhausted, you conduct the last concert of your career. Every conductor acquires a vocabulary of gestures that work for him, that explains what is going on inside. But he should never tie himself down to a system. It is versatility that counts and there must be as many gradations of motion as there are of sound.”

When asked about conductors who were masters, he responded, “Monteux and Toscanini. “Toscanini was my ideal, my hero. We were not always in artistic agreement, but no orchestra ever sounded again the way it did under him.”

Orchestra members who played under Munch offer some insightful comments on his conducting of Berlioz. Principal oboist Ralph Gomberg speaks about Munch’s spontaneity in a performance. “You never knew what was going to happen at a concert. Actually, it was an exciting thing to have. It made it spontaneous. . . . Many times, when we played the last movement of the Fantastic Symphony, it was like an avalanche going down a steep mountain. . . . The adrenaline starts going and you do it. We got out of those performances and we were exhilarated, absolutely exhilarated. . . .”

Cellist Winifred Mayes recalls her first experience of playing the Fantastic with Munch. “It was just incredible to see the excitement that went on in the orchestra as they tried to follow his excitement, his timing and pacing. . . . It was really an inspiration and a joy to play with him. I thought his timing was so incredible, and the nights when he was really on I thought the concerts were absolutely super, and I was swept away. I just could not believe that anyone could take over my whole soul and being, and everyone else’s in the orchestra, and sweep us off our feet the way he did, and the audience, too.”

Harry Shapiro, hornist in the Boston Symphony under Munch, said, “In Berlioz works, you could swear it was Berlioz himself conducting!”

Michel Debost, principal flute in the Orchestre de Paris, observed, “Munch had an almost mystical approach to conducting . . . he brought something to the music that had a certain humanity and mysticism to it. I always looked for this in other conductors but rarely found it.”

John Corigliano, for many years the concertmaster of the New York Philharmonic, expressed his opinion of Munch: “When he conducts, I feel that I’m looking into the face of God.”

I have long admired Munch’s legendary Boston Symphony Orchestra performances of the French repertoire, especially Debussy and Ravel, and his performances of Berlioz I found to be truly magical and transcendental. His interpretations of the Fantastic Symphony continue to send chills up my spine.

Munch made two outstanding recordings of the Fantastic Symphony with the Boston Symphony Orchestra; the first was recorded November 14 and 15, 1954 in one of the first stereo recordings released by RCA, and the second was recorded in 1962. Fortunately, RCA reissued both of these historical performances on compact disc (RCA 82876-67899, and RCA 74321 34168). Munch’s recordings of the Fantastic Symphony were spontaneous, tender, romantic, and intensely explosive and bombastic in the final two movements, and they demonstrate the quintessential and most authoritative performances of this masterpiece. I encourage conductors to study these insightful interpretations with score in hand and learn from a master.

In the May 29, 1969 television broadcast of his Young People’s Concert, titled Berlioz Takes a Trip, Leonard Bernstein described the Fantastic Symphony as “the first psychedelic symphony in history, the first musical description ever made of a trip, a narcotic trip, that ends up taking its hero though hell, screaming at his own funeral.”

Berlioz was only 27 when he composed this imaginative piece that became one of the most influential works of the 19th century. Composed in 1830, only three years after Beethoven’s death, this seminal work was truly fantastic with its unusual and completely new orchestral color effects, large orchestra, and romantic harmonies paving the way for the music of Richard Wagner and Richard Strauss.

Berlioz described the five movements of the Fantastic Symphony as follows: “In the first movement a lover meets the lady of his dream – the ideal woman who is represented by the idee fixe. (This) slow dreamy motive, intended to symbolize the idea of perfect love, is presented in the first movement and serves as a unifying device in other movement in different forms. In the second movement he attends a ball; in the third after killing his love and attempting suicide he marches to his death on the gallows. In the last movement he sees the witches dancing around his coffin after they have held a burlesque of the burial service in which the Dies Irae and the diabolical themes of the dance are intermingled.”

.jpg)

What is also unique about this programmatic symphony is that much of the inspiration is autobiographical. Berlioz’s ideal woman was based on the Irish-English actress Harriet Smithson, whom Berlioz fell madly in love with after seeing her performance in Hamlet. After both families tried to keep them apart, Berlioz attempted suicide by taking an overdose of opium. Eventually Berlioz and Harriet were married but, unfortunately, personalities clashed and joy was short lived. Harriet soon changed from the ideal woman to an alcoholic, and they were divorced after only a few years. Music history, however, can be thankful for Harriet Smithson’s coming into Berlioz’s life, for she served as the inspiration for this autobiographical masterpiece.

On The Art of Conducting: Legendary Conductors of a Golden Era, produced by Teldec Classics, it is possible to observe Munch in a performance of the fifth movement of Berlioz’s Fantastic Symphony. I find his performance truly electrifying and absolutely stunning.

The fifth movement, “Dream of a Witches’ Sabbath, is in four sections: introduction, idee fixe, Dies Irae, and the witches’ round dance. Berlioz’s program notes for the fifth movement demonstrate the literary and macabre thoughts of a raving musical genius: “He sees himself at a witches’ sabbath in the midst of a hideous crowd of ghouls, sorcerers, and monsters of every description, united for his burial. Unearthly sounds, groans, shrieks of laughter, distant cries, to which others respond. The melody of the loved one is heard, but it has lost its character of nobleness and timidity; it is no more than an ignoble dance tune, trivial and grotesque. It is she (Harriet Smithson), who comes to the sabbath as a witch . . . a howl of joy greets her arrival. . . . She mingles with the diabolical orgy . . . the funeral knell, burlesque of the Dies Irae. Dance of the witches. The dance and the Dies Irae combined.”

When watching this video, I am most impressed with the artistic collaboration between Munch and the orchestra members in bringing the diabolical program notes of this fifth movement to life. Munch’s flexibility of rubato and close observance of the dynamics spontaneously evoke all the demonic visions of this strange musical journey. Munch reveals his genius by showing what he wants, adroitly communicating the essence of the work, while, at the same time, giving the ensemble the freedom to breathe and share in the creation of the music. This is the mark of a great conductor.

The fifth movement tempo marking is quarter note = 63, with the Italian directive marked Larghetto. It is in C major and 4/4 time. Munch’s choice of tempo for the beginning of this section is approximately quarter note = 60, which he conducts in four broad strokes. His pacing perfectly captures the sense of the hallucinatory drama about to begin. Most impressive is the range of instrumental colors that Munch brings out through his conducting. Munch was always aware of the myriad color possibilities when he conducted Berlioz and described Berlioz as “the Delacroix of music, painting big frescoes spattered with broad splashes of color. In his book, I Am A Conductor, he explains: “My taste for painting often brings visual images to mind to mix with sounds.” Watching Munch conduct this fifth movement is like observing a great artist painting in sound. Munch brings out a kaleidoscope of colors in the first section of the fifth movement to portray “monsters of every description.” Munch achieves the mysterious and eerie sounds in the first measure by having the muted strings play their tremolo at a pp dynamic, thus allowing the darker color of the celli and basses to bring out their ascending 16th-note runs with a perfectly controlled crescendo going to the quarter notes on the fourth beat, which is marked mf. These opening measures are further enhanced when the timpani enters on the same fourth beat hitting with a sponge beater. Munch’s observance of dynamics in these first measures is never distorted or exaggerated but allows each instrument to be heard with absolutely the right color and Toscanini-like clarity. The descending staccato 16th triplets in measure four remind me of witches cackling around their caldron, much like a scene out of Shakespeare’s Macbeth.

An interesting effect occurs in the high woodwinds when they enter mezzo forte with their sinister exhortations asking other monsters to come to their orgy. They finish their short summons by using a portamento glide from the fourth beat quarter note to an eighth note on the next beat. As far as I know, this is the first time this technique of portamento has been used with woodwinds and creates the perfect eerie effect. The solo horn, marked ppp and muted, answers their summons as if way off in the distance.

The second section, the idee fixe, begins in measure 21 with the clarinet playing a vulgar distortion of the “noble and timid” theme heard in the first movement of the symphony. Here, Munch only hints at the paroxysm about to happen by keeping the clarinet solo ppp over a soft roll on the bass drum and the timpani playing a jig-like quarter note, eighth note, quarter note, eighth note beneath the clarinet. The tempo marking in this 6/8 section is Allegro m.m. dotted quarter note = 112, and Munch’s tempo is dotted quarter note = 116.

.jpg)

Munch’s first musical instruction was from his father, Ernst Munch (1859-1928), who was an Alsatian organist and choral conductor. Munch took lessons from his father on violin, organ, and harmony and counterpoint. His father also taught and directed an orchestra at the Strasbourg Conservatory and allowed Charles to play in the second violin section.

As a boy, Charles met many of his father’s musical friends, including the great Hungarian conductor Arthur Nikisch, composer Vincent d’lndy and Albert Schweitzer, who was the organist for his father’s choir. Charles Munch studied violin at the Strasbourg Conservatory and received his diploma in 1912. For additional training he studied violin with two of the most admired and respected teachers of their time – Carl Flesch in Berlin and Lucien Capet at the Paris Conservatoire. Capet and Flesch were decisive influences on Munch and shaped his concept of violin playing immensely.

Munch’s rapid progress on the violin came to an abrupt halt at the outbreak of World War I. Because Strasbourg was part of the German empire, Munch was drafted into the German army, serving as a sergeant of artillery. He was gassed at Perrone and wounded at Verdun. After the end of the war, Munch returned to Alsace-Lorraine in 1919 and became a naturalized French citizen, professor of violin at the Strasbourg Conservatory, and assistant concertmaster of the Strasbourg Philharmonic Orchestra. From 1926-1933 he was concertmaster of the Leipzig Gewandhaus orchestra under Maestro Wilhelm Furtwangler, who inspired Munch to become a conductor.

Munch came to conducting rather late, at the age of 41, and made his conducting debut in Paris on November 1, 1932. His fiancée, Genevieve Maury, granddaughter of the founder of Nestlé, rented the hall and hired the Walther Staram Orchestra for her future husband’s debut. The concert received outstanding reviews from the critics, and following this success, Munch received invitations to conduct many French orchestras. He also taught conducting at the Paris Conservatoire from 1937 to 1945. Munch’s advice to his conducting students was, “If you interpret music as you feel it, with ardor and faith, with all your heart and with complete conviction, I am certain that even if the critics attack you, God will forgive you.”

During World War II and the difficult years of the German occupation of Paris (1940-1944) Munch continued to teach conducting at the conservatory and was also the conductor of the Societe des Concerts du Conservatoire de Paris, which was the finest orchestra in France. He protected members of this orchestra from the Gestapo and gave his salary to the French Resistance. For this service, he received the Legion d’Honneur from the French government after the war.

My colleague at the Oberlin Conservatory, professor of flute Michel Debost, was a young boy in Paris during the war years and recalls a touching moment he experienced at that time: “My earliest memory of the orchestra is from December 1944, when my mother took me to an orchestra concert on a Saturday morning with Charles Munch conducting. The concert started late, but Munch, who was Alsatian born, stormed onto the stage and told the audience, ‘Strasbourg has just been liberated, so we will play La Marseillaise.’ As the national anthem was performed everyone stood with tears streaming down their faces. This was a poignant moment in my life. Twenty years later when I played for Munch, I didn’t dare tell him of this memory, but I should have because it was so emotional.”

After the war Munch’s reputation as a conductor was meteoric as he received rave reviews in Israel, Prague, and Edinburgh. Charles Munch made his United States debut as a guest conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra on December 27, 1946, and in the 1947-48 season he also conducted the New York Philharmonic. Olin Downes, then the music critic of the New York Times wrote a glowing review of Munch’s conducting, praising his “masterly treatment of phrase, his exceptional range of sonorities, from the nearly inaudible pianissimo to the fortissimo . . . the complete flexibility of beat and capacity that is desirable for romantic rhetoric.”

From 1949-1962 Munch was Music Director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, where he was noted for his excellent interpretations of the French repertoire, especially Berlioz, Debussy, and Ravel. His thirteen-year tenure with the Boston Symphony turned the orchestra into the most French sounding orchestra in America, noted for extreme refinement, spontaneity, and passion.

In his 1955 book, I Am a Conductor, Munch expressed his philosophy of conducting: “. . . it is not a profession at all but a sacred calling. It takes work to make a conductor. You must work from the day you first walk through the conservatory door to the night, when, exhausted, you conduct the last concert of your career. Every conductor acquires a vocabulary of gestures that work for him, that explains what is going on inside. But he should never tie himself down to a system. It is versatility that counts and there must be as many gradations of motion as there are of sound.”

When asked about conductors who were masters, he responded, “Monteux and Toscanini. “Toscanini was my ideal, my hero. We were not always in artistic agreement, but no orchestra ever sounded again the way it did under him.”

Orchestra members who played under Munch offer some insightful comments on his conducting of Berlioz. Principal oboist Ralph Gomberg speaks about Munch’s spontaneity in a performance. “You never knew what was going to happen at a concert. Actually, it was an exciting thing to have. It made it spontaneous. . . . Many times, when we played the last movement of the Fantastic Symphony, it was like an avalanche going down a steep mountain. . . . The adrenaline starts going and you do it. We got out of those performances and we were exhilarated, absolutely exhilarated. . . .”

Cellist Winifred Mayes recalls her first experience of playing the Fantastic with Munch. “It was just incredible to see the excitement that went on in the orchestra as they tried to follow his excitement, his timing and pacing. . . . It was really an inspiration and a joy to play with him. I thought his timing was so incredible, and the nights when he was really on I thought the concerts were absolutely super, and I was swept away. I just could not believe that anyone could take over my whole soul and being, and everyone else’s in the orchestra, and sweep us off our feet the way he did, and the audience, too.”

Harry Shapiro, hornist in the Boston Symphony under Munch, said, “In Berlioz works, you could swear it was Berlioz himself conducting!”

Michel Debost, principal flute in the Orchestre de Paris, observed, “Munch had an almost mystical approach to conducting . . . he brought something to the music that had a certain humanity and mysticism to it. I always looked for this in other conductors but rarely found it.”

John Corigliano, for many years the concertmaster of the New York Philharmonic, expressed his opinion of Munch: “When he conducts, I feel that I’m looking into the face of God.”

I have long admired Munch’s legendary Boston Symphony Orchestra performances of the French repertoire, especially Debussy and Ravel, and his performances of Berlioz I found to be truly magical and transcendental. His interpretations of the Fantastic Symphony continue to send chills up my spine.

Munch made two outstanding recordings of the Fantastic Symphony with the Boston Symphony Orchestra; the first was recorded November 14 and 15, 1954 in one of the first stereo recordings released by RCA, and the second was recorded in 1962. Fortunately, RCA reissued both of these historical performances on compact disc (RCA 82876-67899, and RCA 74321 34168). Munch’s recordings of the Fantastic Symphony were spontaneous, tender, romantic, and intensely explosive and bombastic in the final two movements, and they demonstrate the quintessential and most authoritative performances of this masterpiece. I encourage conductors to study these insightful interpretations with score in hand and learn from a master.

In the May 29, 1969 television broadcast of his Young People’s Concert, titled Berlioz Takes a Trip, Leonard Bernstein described the Fantastic Symphony as “the first psychedelic symphony in history, the first musical description ever made of a trip, a narcotic trip, that ends up taking its hero though hell, screaming at his own funeral.”

Berlioz was only 27 when he composed this imaginative piece that became one of the most influential works of the 19th century. Composed in 1830, only three years after Beethoven’s death, this seminal work was truly fantastic with its unusual and completely new orchestral color effects, large orchestra, and romantic harmonies paving the way for the music of Richard Wagner and Richard Strauss.

Berlioz described the five movements of the Fantastic Symphony as follows: “In the first movement a lover meets the lady of his dream – the ideal woman who is represented by the idee fixe. (This) slow dreamy motive, intended to symbolize the idea of perfect love, is presented in the first movement and serves as a unifying device in other movement in different forms. In the second movement he attends a ball; in the third after killing his love and attempting suicide he marches to his death on the gallows. In the last movement he sees the witches dancing around his coffin after they have held a burlesque of the burial service in which the Dies Irae and the diabolical themes of the dance are intermingled.”

.jpg)

What is also unique about this programmatic symphony is that much of the inspiration is autobiographical. Berlioz’s ideal woman was based on the Irish-English actress Harriet Smithson, whom Berlioz fell madly in love with after seeing her performance in Hamlet. After both families tried to keep them apart, Berlioz attempted suicide by taking an overdose of opium. Eventually Berlioz and Harriet were married but, unfortunately, personalities clashed and joy was short lived. Harriet soon changed from the ideal woman to an alcoholic, and they were divorced after only a few years. Music history, however, can be thankful for Harriet Smithson’s coming into Berlioz’s life, for she served as the inspiration for this autobiographical masterpiece.

On The Art of Conducting: Legendary Conductors of a Golden Era, produced by Teldec Classics, it is possible to observe Munch in a performance of the fifth movement of Berlioz’s Fantastic Symphony. I find his performance truly electrifying and absolutely stunning.

The fifth movement, “Dream of a Witches’ Sabbath, is in four sections: introduction, idee fixe, Dies Irae, and the witches’ round dance. Berlioz’s program notes for the fifth movement demonstrate the literary and macabre thoughts of a raving musical genius: “He sees himself at a witches’ sabbath in the midst of a hideous crowd of ghouls, sorcerers, and monsters of every description, united for his burial. Unearthly sounds, groans, shrieks of laughter, distant cries, to which others respond. The melody of the loved one is heard, but it has lost its character of nobleness and timidity; it is no more than an ignoble dance tune, trivial and grotesque. It is she (Harriet Smithson), who comes to the sabbath as a witch . . . a howl of joy greets her arrival. . . . She mingles with the diabolical orgy . . . the funeral knell, burlesque of the Dies Irae. Dance of the witches. The dance and the Dies Irae combined.”

When watching this video, I am most impressed with the artistic collaboration between Munch and the orchestra members in bringing the diabolical program notes of this fifth movement to life. Munch’s flexibility of rubato and close observance of the dynamics spontaneously evoke all the demonic visions of this strange musical journey. Munch reveals his genius by showing what he wants, adroitly communicating the essence of the work, while, at the same time, giving the ensemble the freedom to breathe and share in the creation of the music. This is the mark of a great conductor.

The fifth movement tempo marking is quarter note = 63, with the Italian directive marked Larghetto. It is in C major and 4/4 time. Munch’s choice of tempo for the beginning of this section is approximately quarter note = 60, which he conducts in four broad strokes. His pacing perfectly captures the sense of the hallucinatory drama about to begin. Most impressive is the range of instrumental colors that Munch brings out through his conducting. Munch was always aware of the myriad color possibilities when he conducted Berlioz and described Berlioz as “the Delacroix of music, painting big frescoes spattered with broad splashes of color. In his book, I Am A Conductor, he explains: “My taste for painting often brings visual images to mind to mix with sounds.” Watching Munch conduct this fifth movement is like observing a great artist painting in sound. Munch brings out a kaleidoscope of colors in the first section of the fifth movement to portray “monsters of every description.” Munch achieves the mysterious and eerie sounds in the first measure by having the muted strings play their tremolo at a pp dynamic, thus allowing the darker color of the celli and basses to bring out their ascending 16th-note runs with a perfectly controlled crescendo going to the quarter notes on the fourth beat, which is marked mf. These opening measures are further enhanced when the timpani enters on the same fourth beat hitting with a sponge beater. Munch’s observance of dynamics in these first measures is never distorted or exaggerated but allows each instrument to be heard with absolutely the right color and Toscanini-like clarity. The descending staccato 16th triplets in measure four remind me of witches cackling around their caldron, much like a scene out of Shakespeare’s Macbeth.

An interesting effect occurs in the high woodwinds when they enter mezzo forte with their sinister exhortations asking other monsters to come to their orgy. They finish their short summons by using a portamento glide from the fourth beat quarter note to an eighth note on the next beat. As far as I know, this is the first time this technique of portamento has been used with woodwinds and creates the perfect eerie effect. The solo horn, marked ppp and muted, answers their summons as if way off in the distance.

The second section, the idee fixe, begins in measure 21 with the clarinet playing a vulgar distortion of the “noble and timid” theme heard in the first movement of the symphony. Here, Munch only hints at the paroxysm about to happen by keeping the clarinet solo ppp over a soft roll on the bass drum and the timpani playing a jig-like quarter note, eighth note, quarter note, eighth note beneath the clarinet. The tempo marking in this 6/8 section is Allegro m.m. dotted quarter note = 112, and Munch’s tempo is dotted quarter note = 116.

.jpg)

When the monsters see that Berlioz’s beloved has come to the sabbath transformed into a witch they let out “howl of joy” at her arrival as the full orchestra comes in ff marked Allegro assai m.m. half note = 76. This is one of most exciting eleven-measure passages in all orchestral literature, and Munch and the Boston Symphony Orchestra perform this diabolical dance with fantastic energy. Munch’s tempo for this section is half note = 20.

In the next section, which is in 68, the idee fixe tempo changes to Allegro m.m. dotted half note = 104, which Munch takes at dotted half note = 112-116. The idee fixe theme is given to the Eb clarinet to capture the beloved as “she joins in the devilish orgies.” It is fascinating to watch Munch navigate the different entrances throughout this psychedelic labyrinth of horror as the rest of the orchestra joins the Eb clarinet with perfect clarity.

At the end of the idee fixe section, the funeral bells make their entrance, which is marked forte and lontano (far away), but Munch brings out their sound for a dramatic effect. This section with the bells always reminds me of the music of Mussorgsky, who was greatly influenced by Berlioz. Mussorgsky wrote after Berlioz’s death: “There are two giants in music, the thinker Beethoven and the super thinker, Berlioz.”

Next Berlioz uses the melody of the Dies Irae (Day of Wrath) composed in the thirteenth century by Thomas of Celano. This is a part of the Roman Catholic Mass for the dead. The theme symbolizes the horrors attending death after a sinful life. Other composers who have used this theme are Liszt, Saint-Saëns, and Rachmaninoff.

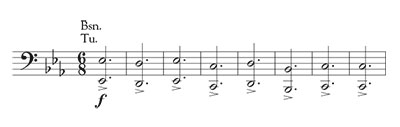

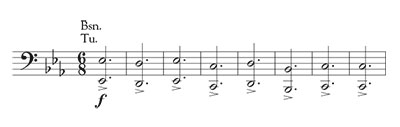

In the Fantastic Symphony the Dies Irae is first played by the tubas and bassoons and Berlioz marks it sempre senza stringendo (always without rushing). Munch makes it even more dramatic and sinister by spacing each dotted half note, releasing it exactly on beat two and bringing out the accents.

After the Dies Irae, the final section is the Witches’ Round Dance, an outstanding version of a Romantic double fugue. This section is very contrapuntal and coloristic and, in many recordings, it is difficult to discern the many moving lines. Munch and the Boston Symphony Orchestra, however, brilliantly bring out the fast flying fragments of the subject and episodes of the fugue.

Mention should also be made of Berlioz’s brilliant orchestration and use of the Dies Irae again in this final movement. Here, it is stated by the winds ff and juxtaposed with the witches’ dance in the strings for one of the major climaxes of the movement. The power and excitement conjured up here by Munch and Boston Symphony Orchestra members as they retain perfect balance with an intense rhythmic drive is truly remarkable.

The symphony ends in a blaze of glory at a blistering tempo of dotted half note = 144. Munch brings out the trombones great example of triple tonguing the last four measures, driving to the final C major chord, which is marked ff. Munch holds this final sound for a full ten counts, ending in an acclimation of triumphant joy.

After his wonderful thirteen-year tenure with the Boston Symphony, Munch returned to Paris in 1962. At the age of 75 Munch formed a new orchestra, The Orchestra de Paris, made up of the best musicians in France. Under Munch’s training the orchestra became one of the best in the world, and in 1968 Munch decided to tour Canada and the United States to secure international recognition. At the New York concert, Karajan, who was there, exclaimed, “It’s absolutely fabulous. Munch has the good fortune to create an orchestra that was already ripe at the beginning and is of such a perfection that I have but a single desire to conduct it.” In Philadelphia, Ormandy expressed the same sentiment, saying, “Marvelous! Absolutely marvelous!”

In Raleigh, North Carolina, November 2 and 3, Munch conducted the Fantastic Symphony for the last time. After arriving in Richmond and getting a room at the John Marshall Hotel, he went to bed. When the valet went to wake him on Wednesday, November 6, he was dead, having suffered a heart attack in the early morning hours.

Memorial services for Munch were held on November 14, 1968 at Boston’s Trinity Church in Copley Square not far from Symphony Hall where he gave so many wonderful concerts. The eulogy was given by the Rev. Theodore P. Ferris, rector of the Trinity Church and a former trustee of the orchestra: “We cannot be sad for him. He had no fear of death, and he died quietly without a single distortion of his body or soul. He had put down his baton after the final chord and walked off the stage of life onto the wings where he is free to be himself, to sing, to soar.”

In the next section, which is in 68, the idee fixe tempo changes to Allegro m.m. dotted half note = 104, which Munch takes at dotted half note = 112-116. The idee fixe theme is given to the Eb clarinet to capture the beloved as “she joins in the devilish orgies.” It is fascinating to watch Munch navigate the different entrances throughout this psychedelic labyrinth of horror as the rest of the orchestra joins the Eb clarinet with perfect clarity.

At the end of the idee fixe section, the funeral bells make their entrance, which is marked forte and lontano (far away), but Munch brings out their sound for a dramatic effect. This section with the bells always reminds me of the music of Mussorgsky, who was greatly influenced by Berlioz. Mussorgsky wrote after Berlioz’s death: “There are two giants in music, the thinker Beethoven and the super thinker, Berlioz.”

Next Berlioz uses the melody of the Dies Irae (Day of Wrath) composed in the thirteenth century by Thomas of Celano. This is a part of the Roman Catholic Mass for the dead. The theme symbolizes the horrors attending death after a sinful life. Other composers who have used this theme are Liszt, Saint-Saëns, and Rachmaninoff.

In the Fantastic Symphony the Dies Irae is first played by the tubas and bassoons and Berlioz marks it sempre senza stringendo (always without rushing). Munch makes it even more dramatic and sinister by spacing each dotted half note, releasing it exactly on beat two and bringing out the accents.

After the Dies Irae, the final section is the Witches’ Round Dance, an outstanding version of a Romantic double fugue. This section is very contrapuntal and coloristic and, in many recordings, it is difficult to discern the many moving lines. Munch and the Boston Symphony Orchestra, however, brilliantly bring out the fast flying fragments of the subject and episodes of the fugue.

Mention should also be made of Berlioz’s brilliant orchestration and use of the Dies Irae again in this final movement. Here, it is stated by the winds ff and juxtaposed with the witches’ dance in the strings for one of the major climaxes of the movement. The power and excitement conjured up here by Munch and Boston Symphony Orchestra members as they retain perfect balance with an intense rhythmic drive is truly remarkable.

The symphony ends in a blaze of glory at a blistering tempo of dotted half note = 144. Munch brings out the trombones great example of triple tonguing the last four measures, driving to the final C major chord, which is marked ff. Munch holds this final sound for a full ten counts, ending in an acclimation of triumphant joy.

After his wonderful thirteen-year tenure with the Boston Symphony, Munch returned to Paris in 1962. At the age of 75 Munch formed a new orchestra, The Orchestra de Paris, made up of the best musicians in France. Under Munch’s training the orchestra became one of the best in the world, and in 1968 Munch decided to tour Canada and the United States to secure international recognition. At the New York concert, Karajan, who was there, exclaimed, “It’s absolutely fabulous. Munch has the good fortune to create an orchestra that was already ripe at the beginning and is of such a perfection that I have but a single desire to conduct it.” In Philadelphia, Ormandy expressed the same sentiment, saying, “Marvelous! Absolutely marvelous!”

In Raleigh, North Carolina, November 2 and 3, Munch conducted the Fantastic Symphony for the last time. After arriving in Richmond and getting a room at the John Marshall Hotel, he went to bed. When the valet went to wake him on Wednesday, November 6, he was dead, having suffered a heart attack in the early morning hours.

Memorial services for Munch were held on November 14, 1968 at Boston’s Trinity Church in Copley Square not far from Symphony Hall where he gave so many wonderful concerts. The eulogy was given by the Rev. Theodore P. Ferris, rector of the Trinity Church and a former trustee of the orchestra: “We cannot be sad for him. He had no fear of death, and he died quietly without a single distortion of his body or soul. He had put down his baton after the final chord and walked off the stage of life onto the wings where he is free to be himself, to sing, to soar.”

References

Charles Munch by D. Kern Holoman (Oxford University Press, 2012).

Discovering Great Music by Roy Hemming (Newmarket Press, 1994, Second Edition).

The Golden Age of Conductors by John W. Knight (Meredith Music Publications, 2010).

I Am A Conductor by Charles Munch, translated by Leonard Burket (Oxford University Press, 1955).