Claude Debussy (1862-1918) was one of the most influential modern composers. He overturned the Romantic era concepts of form, harmony and color and created a body of music characterized by innovation and an individuality of style. Debussy began to compose La Mer (the Sea) in France in 1903. The work was completed in 1905 on the coast of the English Channel in Eastbourne and premiered later that year by the Lamoureux Orchestra, conducted by Camille Chevillard. Typical of many first performances, the composition was not well-received.

La Mer is a three-movement work that falls someplace between a symphony and a tone poem. The orchestral work is scored for 2 flutes and piccolo and is a masterpiece of subtlety and color in orchestral texture.

In a 1903 letter to his publisher, Debussy proposed the composition be titled La Mer: Three symphonic sketches for orchestra. Movement titles were originally to be: Beautiful sea by the bloodthirsty islands, (originally the title of a short story by Camille Mauclair), Play of the waves, and The wind makes the sea dance. However, by the time he finished the work two years later, the title of the first movement had been changed to From dawn to noon on the sea and the last movement to Dialogue of the wind and the sea. These title changes may have happened in an effort to depict the ocean generally, rather than specifically, and to keep the work more suggestive in mood rather than a literal depiction of the ocean. Debussy wrote to a friend “I was destined for the fine career of a sailor” and that “only the accidents of life put me on another path.”

This piece is a perfect example of an understated piccolo part, but one that is extremely gratifying to perform since the piccolo voice so intimately ties into the greater whole of the work. The piccolo part is almost always a solo line. However, the word solo is never written above any entrance.

Listen to a recording of the piece while watching the piccolo part and mark the importance of each entrance. Also notice which instruments double the piccolo line so you can adjust pitch and dynamic balance. This work demands that a centered tone at a piano dynamic. Since most of the solos are in the piccolo’s low register, practice tone studies listening for a clear, warm and focused tone that projects. Fluid triple tonguing (TKT) is another requirement. Before performing La Mer I practice the articulation studies in Paul Edmund-Davies The 28 day Warm Up book (p. 94).

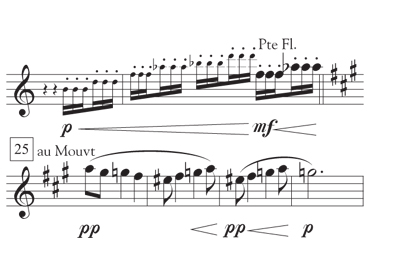

The piccolo part in the first movement consists of a few textural flourishes throughout, but the second movement contains the first important solo at rehearsal 25.

Leave a small space or articulatory silence after the triplet sixteenths to set up the passage after the double bar. While the piccolo doubles the French horn and the violas, this entire line is secondary in importance to the solo oboe. Play one dynamic level under the oboe line throughout.

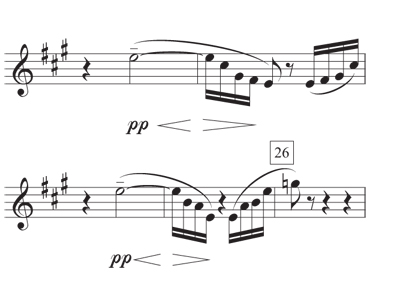

Four measures later there is a delightful passage that intertwines with the principal flute. The flute plays sixteenth-notes on beat two each time, overlapping the first or last notes of the piccolo figure. Listen carefully to match the pitch and color of the flute. Play the first two measures with a leisurely feeling, while adding a bit of direction to the last four sixteenth-notes that lead into rehearsal 26 since the mood changes at the bar line.

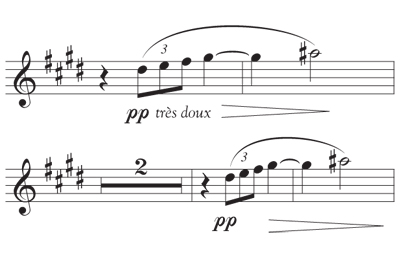

The movement comes to a gentle close at rehearsal 41. The principal trumpet plays triplets on beat one and is muted. Mutes can make a brass instrument go a little sharp, so listen carefully to match the trumpet’s pitch in case the pitch rises. Taper or diminuendo the final A#’s in this figure down to absolutely nothing and allow the mist of the water to permeate your tone color. Keep vibrato narrow and understated so the sound has a dewy sheen and gloss.

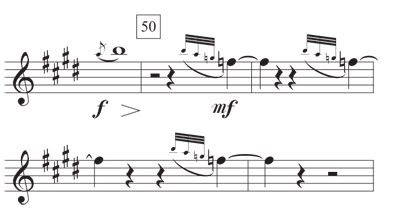

The third movement begins ominously and is quite turbulent as if depicting a storm. The piccolo has repeated figures with grace notes. The English horn is also playing the same figure on beat 2 (piccolo plays on beat 4), so play the grace notes in the same style as the English horn. Most players place the grace notes on the beat.

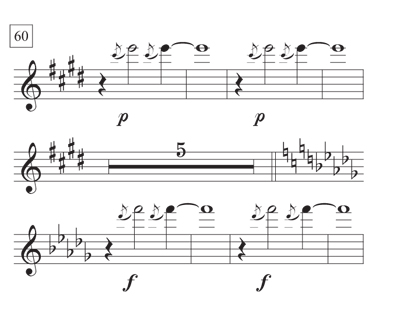

The passage at rehearsal 60 is a prominent line, so keep the tone color very transparent on the piano version of this motive. Play a full and robust forte where it is indicated ten bars later. Notice these graces notes have a slash through them, so the grace notes should be played before the beat but as close to the beat as possible.

The entire work lasts about 24 minutes and is one of the classic masterpieces to perform.

Claude Debussy

(1862-1918)

Claude Debussy was born in Saint-Germain-en-Laye, but moved to Paris when he was 5. His father was a shopkeeper and his mother a seamstress. During the Franco-Prussian war, the family relocated to Cannes where the 7-year-old Debussy began piano lessons. At the age of 10, Debussy entered the Paris Conservatory studying composition, music history and theory, harmony, piano, organ and solfege.

In 1880 he was engaged as the household pianist for Tchaikovsky’s patroness Nadezhda von Meck. Debussy won the Prix de Rome in 1884 which required him to live in Rome for two years. On returning to Paris, he struggled financially, but as his compositions became accepted he became financially secure. He was awarded the Legion d’honneur and appointed to the advisory board of the Conservatory.

Debussy was influenced by the Symbolist poets and used their poetry in his song writing. His most famous orchestra works are Prelude a l’apres-midi d’un faune, La Mer, and Images. Chamber works employing flute are Syrinx (1913) and the Sonata for flute, viola, and harp (1915). Debussy is regarded as one of the chief exponents of French Impressionism in music although he disliked having his music described that way.