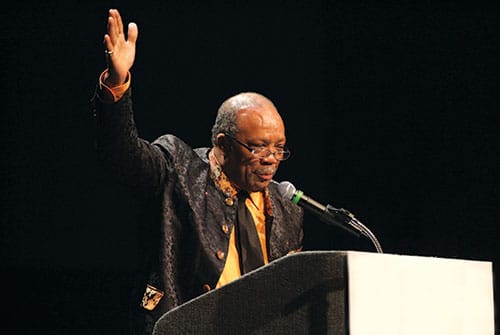

Remembering Quincy Jones

(1933-2024)

Quincy Jones, a multi-talented, multi-genre musician whose enduring influence stretched across several decades, died on November 3, 2024, at age 91. Born in Chicago in 1933, he was raised by his father and grandmother (his mother was institutionalized for schizophrenia). He later moved to Seattle. Jones earned early notice as a jazz trumpeter and joined Lionel Hampton’s band in 1951. Jones got his first taste of recording in Hampton’s band.

Although Jones later had to give up trumpet playing for health reasons, he flourished as a highly-sought after arranger for Count Basie, Frank Sinatra, Dinah Washington, Betty Carter, and Ray Charles. After touring with Dizzy Gillespie on State Department tours of the Mideast and South America, he moved to Paris and studied composition with Nadia Boulanger and Olivier Messiaen.

After taking a position in New York as music director at Mercury Records in 1964, Jones began writing music for film and television including work on In the Heat of the Night, Roots, and The Color Purple. He achieved some of his greatest recognition for his record producing, including three acclaimed albums by Michael Jackson. He also led the creation and recording of We Are The World, released in 1985.

While it is nearly impossible to capture the full range of Jones’s career, he sat down with Ron Modell in 2007, and we include excerpts from this session below.

Are you still writing music?

Absolutely. I am working on the theme for the Special Olympics to be held in Shanghai next October. I am also producing a film in Brazil for a festival that I have attended for the last 52 years. How about this for a combination – an album featuring jazz legend Clark Terry and rapper Snoop Dogg.

When I was 19 years old, Ben Webster told me “Youngblood, when you go overseas or anywhere you travel, eat the food the people eat, listen to the music they listen to, and learn 30-40 words in every language. I learned some Turkish, Greek, French, Swedish, and Japanese. I’ve learned Arabic writing, and I speak Russian. I have a wonderful girlfriend in Shanghai who is teaching me to write and speak Mandarin. It’s a great way to live.

Many years ago Dizzy Gillespie and I went everywhere on State Department-sponsored tours of the Middle East and South America, and we witnessed how far our culture and our music have spread. We listened to everything. Good musicians have an interest in many types of music. We studied Ellington, Bill Evans, and everyone else. Charlie Parker would listen to Stravinsky all night. Nadia Boulanger was Stravinsky’s mentor, as well as Bernstein’s, and she commented that there are only 12 notes to learn; the difference is what everybody does with them. That’s the way we were brought up.

Back when you worked with the Basie band, what did you learn about how to create and play the authentic Basie style?

All of the top arrangers used to hang out at Birdland for Basie’s rehearsal hoping to have their newest pieces played. Among these were Thad Jones, Frank Foster, Johnny Mandel, and Neal Hefti, who was the biggest arranger at the time. One day Hefti came in with a new piece, Lil’ Darling. He wrote it in cut time, and the band started off at a brisk tempo until Basie said, “no, no, no.” The band started over, but at a much slower tempo, and suddenly the music was transformed into a classic, Basie’s trademark piece. The Basie style is all about space economy, tempo, and feel.

As I sat there and watched, this was the greatest moment of my life, and I learned the importance of tempo, or being in the pocket. Being in the pocket is what it’s all about. I couldn’t believe the transformation when Basie pulled the tempo down; it was like walking into another planet. Basie milked every note. I’ll never forget that moment as long as I live.

Sinatra, Ella, Peggy Lee and other singers wanted to sing the way jazz musicians played. That’s the secret, and why they had 70-year careers. On one of the last records we made together, L.A. Is My Lady, as Frank sang, the trombones could barely play because they were listening to how he phrased each line.

Why doesn’t America have a minister of culture? The single most powerful cultural contribution America has given to the world is our music. Everywhere on the planet – Estonia, Monte Carlo, Rio, Sao Paulo, Beijing – they play our music. People have pushed their indigenous music aside and use this music as their Esperanto.

Do you still see a bright future for musicians?

Yes I do because in time the pendulum always swings the other way. The young rappers are at my house all the time. They know that the money will wear off, and the only thing that will be important is to be a real good musician. I’m 74 years old and I feel 22 – I have more work than I could ever do in the next 20 years. The cardinal rule is that you approach your creativity with humility, and treat your success with grace.