Question: How should I practice passages that are difficult for me?

Answer: We all get into the habit of running through something quickly just to say we practiced. It is more important to work on little sections of a piece rather than playing through the whole thing. Running a piece top to bottom without ever correcting a mistake will only solidify mistakes. Start by practicing one small section at a time. The section may be as small as a note or two, a beat, or a measure. As each section improves, connect sections together. Eventually you will be able to play the entire composition with ease.

Tone Quality

Having some practice strategies for the sections helps you work efficiently. Before beginning drill work, be sure you have the best sound you can muster. I recommend the first exercise in Marcel Moyse’s De La Sonorite for developing a beautiful sound throughout all registers. From practice session to practice session, I vary the vibrato speed and colors on this exercise to be sure there is sparkle or ring in the tone. I also vary the dynamics and use a tuner to check the intonation. Not only will this good warmup help you conquer the difficult passage, but it will also benefit your etudes and solo repertoire.

Harmonic work also brings excellent results. The opening of the first exercise in the De La Sonorite may be played at the third harmonic partial. This means for the second octave B, finger a low E and overblow to the third partial. You may continue with third partial notes until you reach the F in the second octave. This type of practice improves embouchure control too.

Technique: Chunks and Rhythm

Play slowly throughout the passage, concentrating on the accuracy of the notes and the coordination of your fingers moving up and down. Use a metronome to ensure accurate timing between your fingers and tongue. As you increase the speed, pay special attention that your fingers are still relaxed and close to the keys.

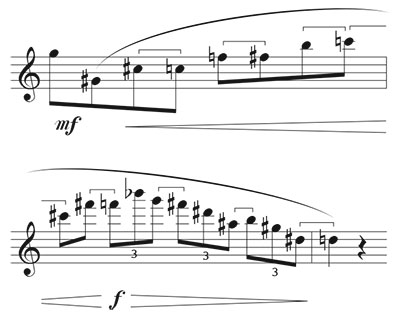

As you are playing through the passage note any patterns in the passage by marking them with a pencil. I use a bracket to show relationships between half steps in diatonic passages. For example, in Paul Hindemith’s Sonate, first movement, I mark the run in the following way:

The brackets help show the brain where the half steps are. On seeing the half steps, the brain can focus on just two notes at a time instead of feeling overwhelmed by the passage as a whole.

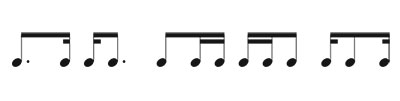

Practicing in chunks and various rhythms also helps input the notes into your brain and coordination. No chunk is ever too small. Make a list of rhythms to apply to passages. Some of my favorites are:

Do realize that the more fundamental practice you do (scales, arpeggios, seventh chords etc.), the easier it is to learn passages. My go-to book is Walfrid Kujala’s The Flutists’s Vade Mecum of Scales, Arpeggios, Trills and Fingering Techniques. This book provides scale exercises in different patterns and modes that help focus on more than just the traditional all-state scale pattern. By practicing technical exercises each day, music becomes easier to put together under your fingers.

Articulation

Even if the passage that is giving you trouble is slurred, practicing with different articulations is helpful. Use T, K, or TK plus a variety of patterns that include a slur. When articulating a note, remember there is the beginning of the note, the middle of the note and the end. All need to be good.

Record Yourself

Since students usually have only one lesson a week, I encourage them to record themselves and critique the recording. Most use a smart phone to easily record and listen to challenging passages. When listening to what they have recorded, I have them focus on the overall quality of sound, evenness of fingers, clarity of sound through larger intervals, and how vibrato sits within their sound. I often have students record themselves with a metronome to make sure the overall pulse within each beat is accurate. Recording oneself is an eye-opening experience that can tell you a lot about your playing that you might miss while in the moment. It also will help you learn to teach yourself.

End Result

The most important part of learning any new piece is the process, not the end result. What matters most is that you put a lot of work into the building blocks that will help you continue to grow as a musician. The more pieces you learn, the more performances you give, the more you work on those fundamentals, the easier this process becomes. Either way, you improve so much more quickly and efficiently by working hard and setting goals for yourself.