As soon as the department stores begin to deck the halls for the holiday shopping onslaught, the airwaves begin to take on a seasonal glow with strains of holiday music to serenade the crowds. One of the hallmarks of the Christmas season for me is the first time I hear a bit of Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker on the radio, and it does not stop there. Performances of the full length ballet are offered to the public by ballet studios at every level, from the home-spun to professional companies who stage top-drawer renditions.

As soon as the department stores begin to deck the halls for the holiday shopping onslaught, the airwaves begin to take on a seasonal glow with strains of holiday music to serenade the crowds. One of the hallmarks of the Christmas season for me is the first time I hear a bit of Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker on the radio, and it does not stop there. Performances of the full length ballet are offered to the public by ballet studios at every level, from the home-spun to professional companies who stage top-drawer renditions.

This work has become a holiday staple and holds up well in the many different adaptations including choreographers who add their own fingerprints to the classic fairy tale (sometimes re-ordering the music to match), jazz versions, rock and roll covers (Emerson, Lake and Palmer’s Nut Rocker comes to mind), animated versions, and even Nutcracker on Ice, where figure skaters tell the story.

Tchaikovsky himself released concert versions of some of the music from the full score (concert suites) before he completed the music for the full ballet. These suites are some of the most recognized and beloved works in the orchestral repertory. The Nutcracker is a short two-act ballet that was commissioned by Ivan Vsevolozhsky, director of the Imperial Theatres, in 1891 and staged the next year. It is an adaptation of the story “The Nutcracker and the Mouse King” by E.T.A. Hoffmann.

As with many works we now regard as masterpieces, the premiere of The Nutcracker was not greeted with particular success, despite the inclusion of the celesta, a new instrument Tchaikovsky chose to feature in the “Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy.” The celesta was invented in 1886 by Auguste Mustel, and Tchaikovsky had heard the instrument on a trip to Paris. Its inclusion in the ballet provides just the right touch for this delicate music.

The score is written for 3 flutes with both second and third flutes doubling piccolo, although the third part contains the major piccolo solos. When playing the full length ballet, it is important that the piccolo player stay in great shape on the flute in the low register because the third flute parts, particularly in the “Dance of the Reed Flutes” and the “Grandfather’s Dance” require dexterity in articulation in the lowest register. Make sure to practice both long tones as well as articulation studies in the first octave as you work on the full ballet score.

Act I

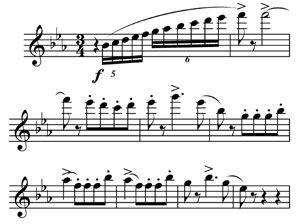

The first little piccolo solo occurs in Number 6, which represents the squeaking of the mice when they come out at night to do battle with the Nutcracker. Both second and third flute play piccolo at this point, and the higher piccolo notes are in the second part. Ask the second flutist to play the lower notes (the ones in the third/piccolo part) and play the notes in the second part as the piccolo specialist. The battle scene that follows is extremely fast: use trill fingerings for the repeated alternating 16th notes when the speed really picks up.

Act II

The beginning of Act II includes a scalar passage that is in the key of E major, but the passage begins and ends on B major. The difficulty here is that the same scale passage repeats 16 times.

It is possible to use harmonics for third octave D#, E, and F# as you go up the scale to avoid possible finger tangles. (overblow G#, A, and B in the second octave to produce those pitches) and then continue on with third octave fingerings from there. Release the top B with as much finesse as possible and keep it light. This music portrays the arrival to the Kingdom of the Sweets: it is painting a picture of make-believe.

The next two examples are part of the entertainment in the Kingdom of Sweets, called the Divertissements. Each dance is in a nationalistic style and represents a food treat of some kind.

The Chocolate variation is in the style of a Spanish dance and this particular solo is doubled with the trumpet. Listen to pitch carefully and bring out the stylized accents that add bravura and flair.

The Chinese dance that follows represents Tea. Check intonation with the principal flutist so that you are together on the octave unison passages.

The final example from this legendary work is accompanied by the celesta again, as the Sugar Plum fairy and the whole company bid farewell to Clara. The passage is marked piano, so play as delicately and smoothly as possible.

After this passage, there is a trill sequence that helps lead the orchestra back to a Valse theme. Crescendo appropriately. I like using the fingering T1 3 1st trill 23 for the G3-A3 trill. My piccolo has a split-E key and this is the fingering with the best response.

I enjoy playing the Nutcracker and try to keep each performance fresh. I remember that for many this may be their only foray into live music for the season! I delight in seeing the young kids all dressed up for the performance with the excitement of the season fresh in their eyes. Have fun with this timeless holiday classic.