Marco Granados is a fabulous flutist who is highly respected throughout the international flute community. I first heard him at the 1997 National Flute Association convention in Chicago, when he broke onto the international scene with his first recording, Amanecer, and first published flute piece, Hibbie Jibbies. It has been fun to watch his meteoric rise during the past 10 years. His trek from rural isolation to stages around the world is a fascinating story.

Marco Granados is a fabulous flutist who is highly respected throughout the international flute community. I first heard him at the 1997 National Flute Association convention in Chicago, when he broke onto the international scene with his first recording, Amanecer, and first published flute piece, Hibbie Jibbies. It has been fun to watch his meteoric rise during the past 10 years. His trek from rural isolation to stages around the world is a fascinating story.

“I grew up in the mountains of Venezuela, very close to the Columbian border. My dad, an avid music afficionado and also a great music teacher, wanted my brother and me to learn musical instruments. However, there were no music schools in our area then. The only way to formally study music was to go to the Conservatory in San Cristóbal, the capital of our state, Táchira, but you had to have a music background to get in. I must have been about 9 at the time, and after some research, my dad decided to start his own music school – the first free music and arts school in Táchira. Once the music school was organized, he received funding for teachers and instruments.

“While I was deciding what instrument to play, the Purdue marching band came through on a Peace Corps tour. They marched through the streets and played a formal concert at the high school. My brother and I went to the concert, but arrived a bit late. The only two seats available were right in front of the flutes and the clarinets. So I wound up playing the flute, and my brother plays the clarinet.”

In the new music school, Granados took music history and theory classes, as well as flute lessons. “My dad taught those courses, and he was a great teacher. His classes were so popular that they were always full. One of the flutists from the State Concert Band drove to our town once a week to teach at the school. He is a good example of how important a teacher can be. I took both piano and flute lessons and actually showed more talent for the piano. However, the piano teacher was mean, and the flute teacher was kind and generous. He spent extra time with his students. I just fell in love with my instrument, largely because of him.”

There is a folk music tradition in Venezuela, similar to that of Brazil. “Until about 30 years ago, the instruments most often used for Venezuelan music included mandolin, clarinet, and saxophone – but not the flute. Then a young flutist named Antonio (Toñito) Naranjo studied in Paris and returned to Venezuela to play in the symphony. He also started playing and arranging Venezuelan folk music. I heard his first record and just went crazy.”

The Venezuelan custom of serenading also played a part in the flutist Granados would become. “As soon as I could play a couple tunes, my dad would drive me around to play at peoples’ homes. It was fun for me because I got to stay up late and go out with my dad. That is when I started playing by ear.”

.jpg) A Teen-Age Professional

A Teen-Age Professional

“When I was 12, there was a second flute opening in the State Concert Band, the one professional organization in Táchira. I decided to try out. They were paying about $1,500 dollars a month, which was an enormous sum then. That summer I started practicing seriously, about six hours a day for the whole summer.

“The audition was in September. My dad thought it was just a whim and humored me, but then I got the job, and Dad was in shock. After much discussion, he said I could take the job, as long as I used the money for education. I had to move to San Cristóbal where I stayed with cousins.

“Immediately my life changed. Because I was in the State Concert Band, I became the flute teacher at my dad’s music school. I went to high school until lunch time, when I left for band rehearsals. Then I took a bus to my town to teach in the late afternoon. The next morning the same routine started all over again. On Friday afternoons, I flew to Caracas twice a month for Saturday morning flute lessons with the piccoloist from the symphony. Saturday night I would take a 13-hour bus ride back to San Cristóbal so I could play a concert with the State Concert Band on Sunday night. This schedule lasted for a year.

“I think about those days and wonder how I did it. When I was 13, I heard the Cleveland Orchestra in Caracas while I was there for a lesson. At intermission I approached one of the orchestra’s violinists, and we started talking. My English wasn’t very good then, but I told him that I was interested in taking a summer flute course. With no internet such information was difficult to get in Venezuela then. To obtain information you went to the embassy, put in a request, and waited. This man took a liking to me, and a month later, a huge packet full of brochures about summer courses arrived. I was like a kid in a candy store going through everything. I picked one called Summer Music Experience, a high school program for the Cleveland Orchestra. I took a small tape recorder into a practice room and recorded everything I knew, back-to-back on both sides of the tape and just sent the tape.

“A month later they phoned my home. My mom answered, but she spoke very little English. All she could understand was that they wanted to give me a scholarship. Then a letter arrived. My dad’s response was, ‘No way. My son is not going to the United States at the age of 14.’ I don’t remember this, but my mom says I waged psychological warfare on him. I started taping notes everywhere he went. In the Bible, in the shaving kit, in the bed, on the door, in the car – all saying, ‘Please let me go!’”

High School in the U.S.

Granados’ father eventually relented, and decided to accompany his son to Cleveland and pick him up at the end of the summer. “On the way there we did some sight-seeing, and at some point, my Dad happened to sit next to a musician from the Cleveland orchestra. He asked the man about the orchestra and the principal flutist. The musician idolized Maurice Sharp and said that Sharp was one of the greatest flutists in America and a legend. My dad thought,‘That’s it. He has to study with Maurice Sharp.’”

During the summer, Granados won the concerto competition, and the camp music director urged him to play for Sharp, who normally only taught graduate students. Sharp agreed to listen to the boy, and after the audition offered Granados a place in his studio. “At age 14, I called to tell my parents that I wasn’t coming home; I was staying in the U.S. to study with Sharp. The camp music director taught at a private school in the winter, and that’s where I went to school. I lived in a dorm and had to learn English. It was a hard transition.”

Granados finished high school in the U.S., focusing on English and math. “Imagine, living in the U.S. for just three months and taking a literature class, where you read Shakespeare and Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. It was difficult, but it was a good experience.”

College in New York

College in New York

After high school, Granados needed to choose a college, but like the rest of his story, his path took many twists and turns. “I wanted to go to Europe and study with Maxence Larrieu, who was teaching in Geneva. I kept trying to contact him and even sent a tape but never received a response. I didn’t prepare to audition anywhere in the U.S., and was subsequently left without anywhere to go. Mr. Sharp was very kind and generous and invited me to come study at the Cleveland Institute, but I had been studying with him and wanted to learn from someone different. I asked him for a letter of recommendation and went to New York without anything lined up there. I arrived in August to find the music schools were already full. I was just 16.”

He went to Juilliard and asked to audition for entrance, but they told him to forget it. He would have to submit an application in the formal way. At the Manhattan School of Music, Granados pleaded to be heard, played an audition, and was accepted on the spot. “I started my first week of classes at Manhattan and stayed in a dorm across from the Lincoln Center. Called the New York Student Center then, there were rooms for $11 a night. Each night I went over to the Lincoln Center to see if I could get in to hear a concert.

Julius Baker

“That’s when I met a young flutist from Juilliard, Elizabeth Mann, who is now one of the leading free-lance flutists in New York City. We talked, and she suggested that we get together to play duets. We set a time, and I went to her apartment. We stated to play and were having a good time when the buzzer rang. To my surprise the door opened and in walked Julius Baker. He was a friend of her family and sometimes used her apartment as a resting place when he was in the city.

“He spoke to me in Spanish and asked me to play something for him. I played a movement of the Khatchuturian Concerto, some Bach, and a Venezuelan folk tune. He looked at me from the couch and asked if I wanted to attend Juilliard. I explained what had happened when I went there. He picked up the phone in the apartment and called the Dean. He told him that he had a student he wanted to take and he was coming to see him right now. He hung up, said come, and we went over to Juilliard. The next day I was enrolled. The really hard part was telling Manhattan that I wouldn’t be back.” Granados studied with Baker for one year – a time he describes as “possibly one of the most difficult years of my life all alone in that big city.”

Jean-Pierre Rampal

Granados was also learning some street smarts and musical protocol. “Rampal was doing a series of masterclasses then at the 92nd Street Y. I was so young, and I didn’t know the proper procedures to follow. I just applied to participate in the classes and was accepted. These masterclasses were open to the public and more like concerts than classes. Rampal and I had a lot of chemistry, and playing for him was fun. Unfortunately, a critic from New Yorker magazine was at one of the classes, and he wrote an article about Rampal and me; Baker wasn’t happy. He called me in after reading the article and said, ‘What’s this? Don’t you know that you are supposed to ask permission?’ I apologized but the damage was done. The incident ended my Juilliard study.”

.jpg) Europe

Europe

Granados went to Europe for a year and worked with Aurele Nicolet. He was then offered a position in the Venezuelan Symphony. “I spent a little over a year as associate principal flute in the Venezuelan Orchestra. I was very young and inexperienced – just 19. When I showed up for the first rehearsal and met the principal, I asked what was being played that week, and he said they were doing Leonore #3 and one of the Beethoven Symphonies. Of course, I assumed that he would be the one to play Leonore, but just before the rehearsal started, he began walking out the door. I asked what was going on. He laughed and replied, “It’s your turn. Go for it.” Right off the bat, I had to learn all of the intricacies of orchestral playing on the job.

“Unfortunately, that year turned out to be a difficult one, because the orchestra had various political problems that eventually led to a division of the group into two separate orchestras. All of that turmoil pushed me to return to the states to finish my studies. Had it been a more positive experience, I might have just stayed in Venezuela.”

To finish his college degree, Granados went to the Mannes College of Music in New York, where he studied with Fritz Kraber for two years. When Kraber moved to Texas, the Mannes flute students were offered the opportunity to choose the teacher they would study with. Granados chose Tom Nyfenger.

Tom Nyfenger

“He really was one of my main teachers. Up until then, I had been a bit lost, bouncing from one teacher to another. Nyfenger was a real genius. In my previous teachers’ estimations, I played well, but I continued to be frustrated with my sound. When I started working with Nyfenger I got a better understanding of how to produce the sounds that I wanted. Although he could be opinionated, Nyfenger was the most open-minded teacher about style that I had. He understood what I was going after and let me try for it. Some of my other teachers would frown if I was playing the lower register too loud or not understand what I was looking for. Nyfenger knew how to direct that.

“Probably because I was a young player, my practicing was too fast and wild. Nyfenger taught me to practice properly, and he did it in a way that I will always remember. He wanted me to slow everything down, and I remember vividly a lesson on Andersen etudes. It was an etude with lots of 16th-note sextuplets. I started playing – fast – and he let me go through the first page. I thought, ‘Oh, good, I’m going to get to the end,’ but he stopped me and said, ‘Take the repeat.’ Half way through the repeat he exploded, screaming, ‘What is this? You’re playing the same chord wrong. I’m not a policeman of notes. If you don’t do it right, I’m going to find something better to do with my time.’ He was really upset. ‘Play it again, and play it slowly.’ He never told me which chord was wrong; I had to figure it out. I got through the first page, playing it slowly, and finally got to the end.

“A small picture of Marcel Moyse hung on Nyfenger’s studio wall. Nyfenger walked slowly over to me, and in a split second grabbed me by the shirt, put my face right next to the picture and said, ‘You see – he’s watching us.’ Nyfenger would not accept something that wasn’t up to a certain level. You had to play the right dynamics, the right phrasing, the right notes.”

Teaching

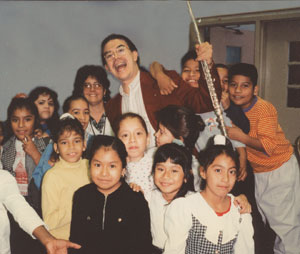

Granados plays a lot of Latin American music in many various forms, is involved with chamber music, and does some solo work and masterclasses. While he doesn’t teach much these days, he hopes to have a full-time teaching position at some point. “I love to teach. I know that eventually a full-time position will come. I do a lot of composition workshops with elementary-age school kids in large groups. These are residencies established with a school for several days. I get the children to understand patterns and rhythms, and then they work with various percussion instruments. They divide into small groups and create different rhythmic patterns. At the end of the residency, I compose with everybody’s ideas.”

When asked if there were any specific teaching experiences that he would like to share he told an incredible story of a workshop in South Africa. “In 2003 I played a concerto with the Johannesburg Philharmonic in South Africa and was very curious about the culture and people. I was particularly interested in finding out what was happening musically in Soweto. After the first or second rehearsal I struck up a conversation with the principal flutist in the orchestra, who worked with Soweto children. She said the need was so great that music teachers couldn’t keep up with the demands. Most of the time they had to turn away children who were begging for lessons.

“I offered to help, and she arranged for me to teach at three different schools. The first one was an elementary school, and I was shocked to discover dirt classrooms floors. Most of the desks were broken, and the band instruments they had were barely working – many held together with rubber bands. About 80 kids from about 5th grade through high school came, and they were as curious about me as I was about them.

“We started doing a rhythm workshop that turned into a composition workshop. The class was to last an hour, but when the time was up, they were still to eager to learn. We just kept going, and the workshop turned into a giant jam session, with students taking turns playing solos on various instruments. By the time I looked at my watch, the class had gone well over two hours. As we finished, I noticed that some of the students continued to practice and play. Two of them were about fourth or fifth grade flute players. One of the boys looked a little weak physically, but he was a wonderful musician – he wrote his own songs and improvised. He was a very mature musician for just 10 years old. When I returned to New York, I posted their photos on my web page. About a month later I found out that the weak-looking boy had died of AIDS. Music was the one thing that had kept him going. My experiences working with these young people really reminded me that this is why I play the flute.”

Composing

Rhythm is at the heart of Marco Granados, both in his performing and compositions. “My life as a composer happened by chance. I had written Hibbie Jibbies as a fun exercise for myself. I was on tour in Montana with a woodwind quintet, when our oboist was hospitalized with food poisoning. There were still two more concerts to play on the tour, so we started scrambling to find music that would work without the oboe player, including some solo works. The presenters agreed that we could play a mixed-repertoire concert rather than quintet literature, and we asked friends in New York to ship music to us. Unfortunately, the program was still too short. Up to that point, I had never played Hibbie Jibbies in public, only by myself as a type of exercise. Out of necessity I played it in that concert, and it was so well received that I wrote it down and began performing it. The next place I played it was at the N.F.A. convention in Orlando, Florida.

“Composition is a big part of my performing; it emerges out of my improvisations. Although I have been commissioned a few times, including by the National Flute Association, I don’t yet consider myself a full-time composer. Composition has been an outgrowth of playing Venezuelan music. In fact, most of my compositions are based on Venezuelan music. I try to make the connection between what the flute can do and traditional Venezuelan rhythms and traditions.”

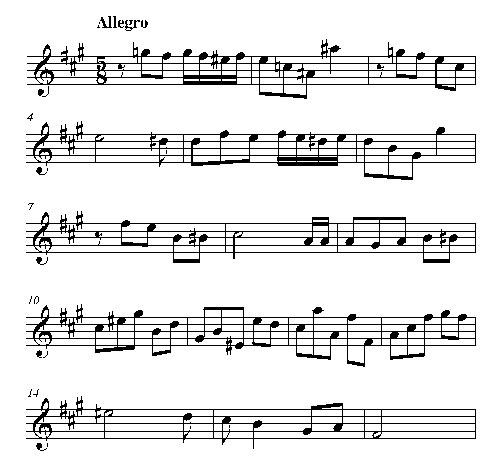

He also makes that connection with Un Mundo, his flute, cello, and piano trio that is dedicated to bringing the passion and energy of Venezuelan music to the world, instilling in young people the love of music, and bridging cultures through classical, folk, and jazzy arrangements. His eyes light up when he talks about Venezuelan music and traditional South American rhythms. “Venezuelan music rhythms are even more complex than other South American traditional rhythms. Cross-rhythms, odd meters, switching meters, and phrasing against the rhythm are sometimes a bit of a challenge for classically trained people. A typical such rhythm is the Merengue, which is in 5/8. It goes pretty fast, 12345, 12345, 12345, and the bass has beats 1 and 4. The flute can often have melodies of all 8th notes, and the downbeats are delayed a little bit.”

Performing

Granados describes himself as a Jack of All Trades. “Since moving to New York I have gone from playing in the subway to recording studios, from Broadway shows to chamber music. There have been several different phases to my career. There was a time when I mainly freelanced as an orchestral player, then I worked as a Broadway musician for several years. Over the past 10 years, besides concentrating on a solo career, I have been very involved with playing chamber music. I guess I’m sort of a freelancer. I play with many different groups, as well as with the Chamber Music Society at Lincoln Center from time to time.”

Despite his humility, Granados is much more than a freelancer. He has performed with the Quintet of the Americas and worked with such distinguished artists as Paquito D’Rivera, flutist Ransom Wilson, harpist Nancy Allen, oboist Heinz Holliger, flutist William Bennett, as well as with soprano Renee Fleming and baritone Dwayne Croft. He recently self-produced a new C.D., Music of Venezuela, that has now been taken over by Soundbrush Records, his new label. They offered him a two-record contract, and a second recording is in the works. His previous recordings include Luna, a romantic serenade of songs from Venezuela and South America for flute and guitar, Tango Dreams, a compilation of works by Astor Piazzolla, and Amanecer. His many performance videos are available on YouTube, and his personal web page is http://www.sunflute.com/.