As a young professional in the early stages of a career, just suppose there would be a way to learn about tried-and-true teaching techniques from experts, keep abreast of excellent new products and materials to use in one’s work, see the faces, discover the leaders in your profession, and find opportunities to widen one’s knowledge and education. There was and still is a way that provides all of this.

Ties – One Thing Leads to Another

The following story is my story about the magazine and me. Growing up, I had a great uncle who was then a retired policeman. He loved band music and one evening took me to hear a concert by the Milwaukee Police Band.1 The program ended with a performance of The Stars and Stripes Forever complete with an American flag unfurling above the stage at the end. That did it. The thrill of hearing that march and being a part of the audience’s response was electrifying. Right there, I fell in love with the music of John Philip Sousa.

By the time I graduated from college to begin my teaching career, the novel idea of such a musical group called a wind ensemble was taking hold in this country. One of its champions was Frederick Fennell, and his hero was the same as mine – Sousa. I owned the Eastman recordings of Sousa marches and wanted to know as much as possible about the music and the man. Also just at that point articles by Paul Bierley were appearing in The Instrumentalist.

In short order as he published his landmark books about the life and music of Sousa, I acquired each, especially poring over the descriptive catalog of his works.2 With the bicentennial approaching in 1976, I wondered if I could program a full concert of Sousa’s lesser-known marches, suites, and novelties. I needed to acquire the music.

After consulting the University of Illinois Sousa Archivist and the Library of Congress, I was referred to a man by the name of Robert Hoe who could perhaps cut through the red tape and help. I recognized his name from The Instrumentalist in connection with a comprehensive recording project underway by the United States Marine Corps Band entitled The Heritage of John Philip Sousa.

I telephoned him immediately, and within days, I had all the music I was seeking. In a letter inside the box of parts, he explained, “Your phone call was so plaintive I am compelled to aid you all I can. You sure as hell picked some wild ones, for this is rough stuff.” I was excited to meet Bob at the Midwest Clinic that December and told him how we were already rehearsing the music for the upcoming winter concert in March.3

The band played beautifully, and the concert was a huge success. I decided to write and submit an article about it to The Instrumentalist. To my delight, the article was accepted and published along with a portrait of Sousa that I had done as a program cover. Shortly thereafter I was surprised to receive a wonderful letter from Paul Bierley saying, “Wish I could have been at your Sousa concert. You’re some artist, I mean to tell you. That portrait of Sousa is great.” That eventually led to an ongoing friendship and my doing the cover portrait of his Hallelujah Trombone!, the first edition of his Henry Fillmore biography.

Original cover of Paul Bierley’s book Hallelujah Trombone! The Story of Henry Fillmore

Some years later my wife and I spent a great afternoon visiting Paul and his wife Pauline in their home in Columbus, Ohio which was filled with mountains of Sousa and band research materials. He graciously signed my copies of his books, one inscription which read, “Every possible good wish to my dear friend Tom Trimborn. Sousa can’t sign this so his high-priced biographer (in the low-priced field that is) will. (stop laughing).”4 Cherished memories to be sure.

In my 16 years at Palatine (Illinois) High School, the Symphonic Band presented three formal concerts a year. Every one included a Sousa march with only one repeat, The Stars and Stripes Forever. As I worked toward earning a PhD in Music Education at Northwestern University, I was sure that a dissertation topic would be Sousa related in some way. Even though that did not happen, my focus shifted to identifying and establishing a curriculum of cornerstone wind literature for school bands in large part due to Frederick Fennell, who in my opinion was second only to Sousa in the influence he was having on the concert band medium in establishing a foundational repertoire.

I devoured his 16 Instrumentalist articles on basic band classics and the stunning landmark recordings he made with the Eastman Wind Ensemble. In the fall of 1981, eager to begin a yearlong residency at Northwestern University, I looked forward to discussing this topic with Director of Bands John Paynter, another early and important champion of contemporary wind literature and whose reviews I regularly devoured. But then bad news. He had had a heart attack and would be recovering for quite some time.

However, just as suddenly, it was announced that none other than Frederick Fennell would be stepping in for Mr. Paynter during his recovery. To my delight, I got to observe and chat with Dr. Fennell regularly about wind band repertory. In one memorable conversation, he told me that the stunning recording of William Walton’s Crown Imperial was done in one take. Thankfully, when John Paynter returned for the spring semester, he graciously agreed to supervise my independent study of Sousa’s Songs of Grace and Glory, and also to discuss what he considered to be cornerstone literature. I was indeed learning, observing, and interacting with the movers and shakers of the wind band world – the ones I had first met in print.

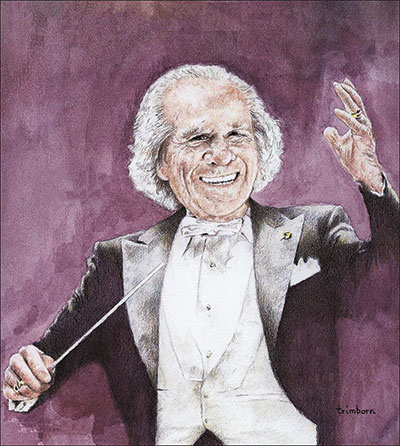

During my 21 years at Truman State University, I had the privilege of doing the artwork appearing on the cover of the Missouri Music Educators Association magazine. For an issue with the theme Legacy, I simply had to do a portrait of the Frederick Fennell I knew. He indeed was aware of the direct line back to Sousa when he wrote to me, “My three days with him (at Interlochen) left their mark which still shows.”5

Original portrait of Frederick Fennell now in the Bonisteel Music Library at the Interlochen Center for the Arts, Interlochen, Michigan.

Talk about full circle and how one event or meeting often leads to another and back again. For me, the connection always was The Instrumentalist. Today, as communication tends to be exclusively via the internet, fine as it is, having concrete printed documentation of the world of music also remains of paramount importance. Pioneers, innovation, and creativity abound and chapters still will be written. In this 80th anniversary year, it is good to look back, but also look forward to a future 100th anniversary. The past we are creating now, without question, will be an extension of a heritage to be celebrated.

Sousa Still A Somebody?6

Is Sousa still important? Relevant? If so, why? Over these 80 years, the magazine has in many ways kept the spirit of Sousa alive. Just in the last 20 years, books, articles, scholarly papers, authentic recordings, and full scores, have appeared and are underway testifying to Sousa’s continued importance. He is relevant because his music is not only universal but is imbued with what might be called the American spirit. His masterful marches are what some compare to a three-minute egg – the all in one perfect food – having proteins, vitamins, and minerals – or in the case of his marches “clear structure, rhythmic drive, great melodies, dynamic contrast” – and much more. And all in three minutes. In his day, Sousa programmed his popular marches, suites, descriptive pieces, and novelties along with the music of Beethoven, Mendelssohn, and Puccini. He played Wagner’s Parsifal in Grand Forks, North Dakota 10 years before it was heard at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York.

With the arrival of Frederick Fennell, the importance of playing Sousa along with the music of Holst, Grainger, and Persichetti reminds us not to forget the past, but to cherish it, embracing the present while looking to the future. Contemporary pieces and composers, orchestral transcriptions, and yes, the important music of John Philip Sousa, can and will always make interesting, educational, satisfying programs. And surely, we have read about all of this and will continue to do so making all sorts of connections via The Instrumentalist for many more years to come.7 For me, I will always be thankful for my Instrumentalist ties.

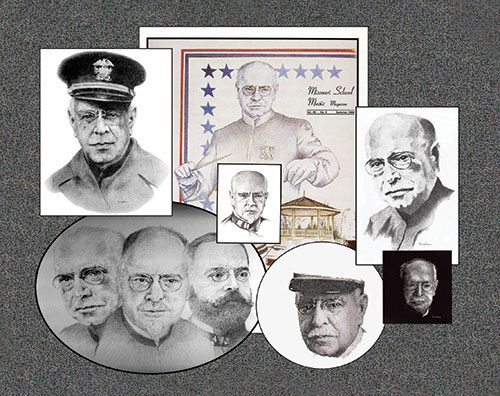

The many portraits of Sousa by Tom Trimborn

End Notes

1The Milwaukee Police Band is the oldest police band in the United States, established in 1898. In 1923 at the conclusion of a performance at the Milwaukee Auditorium, Sousa conducted his Sousa Band plus the Police Band in two marches, his Sabre and Spurs and Comrades of the Legion.

2These books and those that followed firmly established Bierley as a preeminent Sousa authority. Bierley, Paul E., John Philip Sousa: American Phenomenon, Prentice Hall, 1973 is an authentic comprehensive biography of Sousa’s life, work, and literary output. Bierley, Paul E., John Philip Sousa: A Descriptive Catalog of His Works, University of Illinois Press, 1973 not only listed for the first time Sousa’s original compositions, but his arrangements, transcriptions of other composer’s works, plus magazine and newspaper articles by and about him. Copyright history, publishing data, and the whereabouts of his manuscripts were also included.

3The Heritage of John Philip Sousa refers to 9 volume set of 18 LP records of his music, performed by the United States Marine Band under the direction of Lt. Col. Jack T. Kline from 1974-76 funded and released by Robert Hoe of Poughkeepsie, New York. The collection includes not only Sousa’s well-known marches, but also waltzes, suites, fantasies, and selections from his operettas.

4Bierley, Paul E. Hallelujah Trombone! The Story of Henry Fillmore, Integrity Press, 1982 has my portrait of Fillmore on the cover and a dual portrait in chapter 66 Twilight of the University of Miami President Jay F.W. Pearson with Fillmore receiving an honorary doctorate.

5Fennell played bass drum in the National High School Band under Sousa in 1931 at the Interlachen Music Camp. My portrait of him is now housed in the Bonisteel Music Library there.

6The title of an article written by Frederick Fennell appeared in the March, 1982 issue of The Instrumentalist.

7A select list of those authors, conductors, and ensembles who have essentially told the story of Sousa, his music, and shaped the wind band ensemble as we know it today includes but is not limited to: Berger, Kenneth; Bierley, Paul; Bourgeois, Col. John; Brion, Keith; Byrne, Frank; Dvorak, Thomas; Foster, Robert; Hunsberger, Donald; Lingg, Ann; Revelli, William D.; Schissel, Loras; Smith, Leonard B.; Trimborn, Thomas; Warfield, Patrick; Dallas Wind Symphony; Eastman Wind Ensemble; New Sousa Band; Philip Jones Brass Ensemble; Royal Artillery Band; United States Marine Band; University of Michigan Band.