Compilations of Great Ideas and Advice from The Instrumentalist Archives

The Art of Conducting

By Donald Hunsberger

May 1998

Donald Hunsberger was conductor of the Eastman Wind Ensemble from 1965 to 2002.

Ideally, conductors would not say a word. They would stand on the podium and physically demonstrate how the music should sound. Although this ideal is unattainable, talking should be kept to a minimum. If the first oboe player has a solo, I let them play it several times before saying anything so they can first become comfortable with the line. When I do speak, it is usually to present options rather than to give instructions. I may suggest working on the solo with their teacher, who will probably open more options. Even if the teacher doesn’t know the solo, they can offer an objective point of view. I don’t dictate how to play a solo because it will sound better if the performer develops an interpretation rather than reproducing by rote a version given by another musician.

My goal is to produce musicians who can play anything. At Eastman, I introduce students to a lot of good literature, from Sousa marches to aleatoric compositions, and some they may never play again. I don’t try to teach students every composition they might play in the future but try to give them the ability to sit down and play anything put in front of them. Students switch parts on almost every piece within a concert depending on the instrumentation. The intention is that a flutist, for example, will become as comfortable playing principal as performing piccolo, second, or third part. The faculty prefers to use and assign different groups of students for each concert.

Overconducting

By Maurice Faulkner

August 1988

Maurice Faulkner taught in Department of Music at Santa Barbara State College from 1940 until his retirement in 1979. He was also widely published as an author and critic.

The young conductor should select a first-rate example of a conducting specialist whose work satisfies them and try to copy the style. For my taste, Herbert von Karajan, with his easy, soft beat and infrequent cues, expresses the essence of the scores with little excess motion. His program of Wagner masterpieces at a Salzburg Festival, all conducted without a score, reached the peak of sensitive interpretation. A less graceful baton wielder, Carlo Maria Giulini, creates the same feeling of serenity while developing the power essential to the fortissimos.

At the Salzburg Festival some years ago, von Karajan was responsible for conducting the Cleveland Symphony one evening. After the performance of one of the works on the program, a Clevelander told me, “We certainly had a difficult time following his beat, but he sure let us play with our hearts.”

Depend upon your musicians and realize that they are talented, even when they are only beginners. The finer the musician, the less help is needed from the conductor. A well-trained orchestra or band should be able to play effectively without a conductor. Try it sometime on a concert, and you will soon discover whether you have taught them properly.

Col. Arnald D. Gabriel

October 1981

Col. Gabriel was Commander and Conductor of the United States Air Force Band, United States Air Force Symphony Orchestra, and Singing Sergeants from 1964 to 1985. He has conducted hundreds of major orchestras and bands and recently turned 100.

The older I get, the more I realize that you don’t have to be a tyrant. If you’re secure with your art and your profession, it’s unnecessary to talk down to anybody, or to berate, or to raise your voice. If I do, it’s only because they’re being inattentive or something of that sort, It’s not related to our ability to make music together. We conductors have to realize that we are not the most important elements. The composer is, the truth that is in that score. We are just the re-creators. The performing organization and conductor together make the music, and there has to be mutual respect and admiration. I admire my groups, and I hope that they have respect for the knowledge I have of the score. By working together, we can re-create the work.

I don’t use a baton. It has become smaller and less important since Lully hit himself in the foot, developed gangrene, and died. That made him stop pounding the floor. It still seems to me that too many conductors use the baton as a symbol of authority, and I don’t think we need that. I believe a baton invokes a certain fear, and there should be no fear in making music. There should be respect. We should get away from the stick, which seems to be that symbol of the kind of authority that people resent.

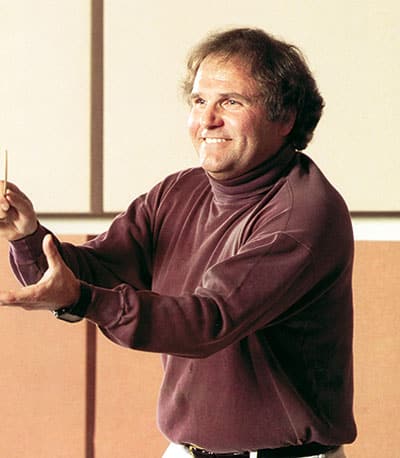

Teaching Other Conductors

By John Paynter

July 1979

One of the most influential band directors of the 20th Century, John Paynter was Director of Bands at Northwestern University from 1953 to 1996. He was the original new music reviewer for The Instrumentalist.

Each teacher and each conductor is really an individual personality, and it’s within that personality that the band has either its successes or its problems. Two things often stand out as general weaknesses. The first is musical – the failure to recognize the things that don’t sound like music. A good conductor must be able to hear what is going on, while it is going on, and suggest what to do to change it. So many of our people are well-trained to read the score, and well-trained to lead with a baton, but they are not really well-trained to hear what’s going on and change it. As a consequence, some basically unmusical, inflexible, and unnuanced things continue to happen. The other thing is personal. A lot of potentially wonderful teachers aren’t doing a very good job because they are too frustrated by all of the mechanical and personal things that can get in the way. A band director must enjoy what they are doing, be head-over-heels in love with it, to work around the technical problems and push through to the job of having fun and making music.

Advice for Conducting Students

By Cynthia Johnston Turner

October 2018

Cynthia Johnston Turner was appointed Dean – Faculty of Music at Wilfrid Laurier University in Waterloo, Ontario, in 2021. When this interview took place, she was Director of Bands and Professor of Music at the University of Georgia.

Be yourself. I see a lot of posturing on the podium as students try to look and be like somebody else. Figuring yourself out can be a life-long journey. I know it took me a long time. The self is constantly changing and evolving. The process starts with some soul-searching. Often it involves writing down their thoughts from rehearsals, watching conducting videos, and determining what they like and don’t like. Students often conduct a certain way, but when I talk with them in a relaxed setting, they speak differently.

Conducting students also have to become more aware of the different ways their bodies move on the podium. I encourage my students to take classes in movement, whether that is dance, yoga, tai chi, Alexander technique, acting, or public speaking. Often the things that make people better conductors aren’t related to conducting. They are related to psychology, self-analysis, body awareness, and mind awareness. These areas help people become more intuitive about who they are. As young conductors grow more comfortable on the podium, they learn that it is okay to be vulnerable.

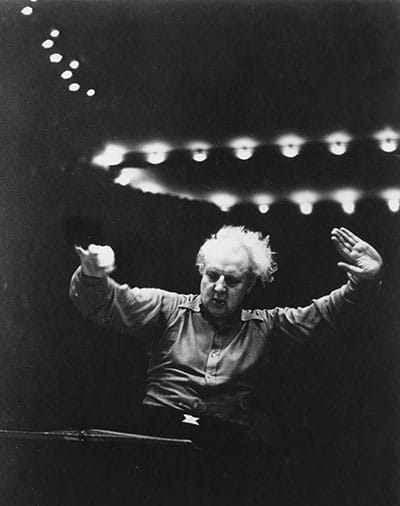

A Lesson from Stokowski

By Legh W. Burns

January 1977

When this article appeared, Legh W. Burns was the music director and conductor of The Saratoga Chamber Orchestra. He was also Professor Emeritus of the University of Oklahoma School of Music and former first trumpet with the United States Air Force Band in Washington DC.

We were all there. The University of Miami Symphony Orchestra, rehearsed, capable, and hot. The concert was to take place the following weekend, and our guest conductor for the occasion had just arrived. Leopold Stokowski. He stood quietly on the podium, dignified, powerful, and with the awe of us all surrounding him. He was being introduced by John Bitter, our regular (not to say ordinary) conductor and former pupil of Maestro Stokowski. The day was especially hot and the introduction, because of the circumstance and association, extra long. Accolades like “superior musician” and “pioneer” began to make their way back to the trumpet section where I sat. “Inspirational,” they continued, “influential.” The maestro looked down at the music (among other pieces, this concert was to feature the Tchaikovsky Symphony No. 4). His face was expressionless, the thin strands of white hair in careful disarray.

Finally, the introduction came to an end. Mr. Stokowski was presented to us, and the applause burst forth from the orchestra with a spontaneity and obvious sincerity that impressed me very much. We waited for the acknowledgment from the maestro. A “thank you” for certain, followed by the usual “nice to be here” and perhaps a story or two of the Stokowski-Bitter association that would start the rehearsal off on a cordial and familiar footing. We waited. Still, the gaunt, lined face looked at the stand. Silence. Then, the head finally lifted and he spoke: “Tchaikovsky please, 1st movement.” After that, things happened so fast our heads spun. No one had his music ready, and the resulting shuffle of parts was clearly annoying to Maestro Stokowski. “Letter A,” was followed all but simultaneously by a downbeat. Letter A? Half of us hadn’t found our music yet. The trumpet section, never noted for being on top of things, grumbled the loudest.

Well, it went on like that for the entire week. We were angry at first, half at Mr. Stokowski for moving at an intolerable speed and half at ourselves for letting his half make us angry. The second rehearsal found us determined to stay with him, and towards the end of it we were all speed readers. You would have thought Evelyn Wood was on the podium. Well, it got better and better. Rehearsals became a challenge, and the intensity with which Mr. Stokowski approached each note began to be infused in us as well. Everything improved. Everything! As this transformation was taking place, I began to develop a warm affection for him. He had a technique of rehearsal I had never seen before. It moved very fast but always with a purpose. We soon learned to stop when he did, for the direction (which soon supplanted correction) was only given once.

By concert time, we were all inspired as we had never been before, and speaking for myself, as I have not been since. The concert was outstanding. I have played many concerts since, but will remember that one above all others.

Score Study

By H. Robert Reynolds

May 1973

H. Robert Reynolds is Principal Conductor of the Wind Ensemble at the University of Southern California and was previously Director of University Bands at the University of Michigan for 26 years.

The question is often asked, “How do you study a score?” There is no system that applies to all scores and all conductors. One approaches a new score as one approaches a crossword puzzle – by trying to discover several key ideas that will lead to a complete understanding of the work. Each composition is a new experience and presents a challenge to the conductor. And it is here that the conductor calls upon the study of theory, counterpoint, form, history, and other aspects of formal and informal training. Naturally, knowledge of the composers complete works, styles, and biography is of vital importance, as are specific facts regarding the piece under study and its relation to the other works by the composer.

Implicit in the knowledge of the score is the conductor’s personal concept of all details such as balance, weight, emphasis, and phrasing that make one conductor’s interpretation different from that of another. Most composers expect the conductor to use his musical judgment to interpret the idea of the composition. As an example, several years ago I was rehearsing Emblems by Aaron Copland while the composer himself was present. When I looked through the score in my study, I felt that the tempo marked in one section was too fast. During the rehearsal of this section, I turned to Mr. Copland to ask if the section was too slow for his liking. He commented that he would have conducted it faster but that it was musical and should not be changed to the faster tempo indicated. I offered to change the tempo to suit him, but he insisted that it be an interpretation that I felt best for his piece. Composers, with the exception of Stravinsky and a few others, expect the conductor to bring his own interpretation to the work, as long as it is consistent with the stylistic traditions of the period and other guidelines already mentioned.

Communicating Better

Anthony Maiello

March 1994

Anthony J. Maiello is Professor of Music and University Professor at George Mason University.

If you could retrain every director in the country, what would you want to teach them?

How to communicate. Conductors are supposed to be great communicators, yet we don’t know how to communicate. Many directors have become guarded. I have witnessed brilliant musical minds who are walking music encyclopedias but lack the ability to communicate their knowledge. Communication skills are one of the topics I cover in conducting clinics, and it certainly would head the list of subjects for teachers returning to the classroom. All the knowledge in the world is useless if you cannot share it.

How can directors become better at communicating?

During clinics, I emphasize that aside from the musical aspects of the score, conductors should have experience in acting, dance, and mime. Familiarity with these areas will teach a conductor to use their body. After all, conducting is a silent art. Directors have to indicate what they want to hear through gesture, acting, and body language, and anything other than speaking. At clinics, I ask people to start an ensemble and conduct a piece without using their hands. A posture or facial expression will do. I’m big on facial expressions: the eyes, eyebrows, or mouth. The conductor can use any of these except the spoken word. I show clinic audiences how to use gestures instead of words to convey instructions. Unless a conductor can demonstrate the sound they want, it will not happen. If inspiration does not come from within the conductor, it will not emerge in the music.

Teaching Expressive Conducting

By Craig Kirchhoff

June 1994

Craig Kirchhoff is professor emeritus of conducting at the University of Minnesota and a past president of the College Band Directors National Association.

All conductors should have a distinctive body language. I have no interest in changing students into carbon copies. I take their gestures and clarify them. Some conductors use so much motion that it is hard to identify what they want to achieve. Less motion is best for communicating with players and for hearing the ensemble. Most directors have discovered that they hear better off the podium, as when driving home listening to a recording, than when standing on the box waving their arms.

I recommend that every conductor get a videotape of Carlos Kleiber conducting. He is probably the single most remarkable conductor I have seen. I specifically remember a performance of Beethoven’s Seventh with the Vienna Philharmonic. He never used a discernible time pattern. We are taught that conducting is time patterns, but his gestures were almost child-like. His motions simply described the pure essence of the music.

How do these concepts of conducting affect the way you structure a rehearsal?

I try to project how the rehearsal will proceed and what we should accomplish, but I always have a plan for each session. I often deviate from the plan to deal with whatever problems arise, but rehearsals should have an architecture. The most effective conductors change the energy level at various points in a rehearsal. There should be moments of incredible, white heat as well as moments of wonderful quiet. The different energy levels keep everyone involved in the music. When the energy level never varies, rehearsals become predictable and concentration fades. I have found over the years that the best rehearsals have focused on musical issues and not technical matters. A certain of amount of rehearsal time should be spent on developing the technique to express music, but the key is for musical issues to drive the technical issues. If I give students musical reasons for improving these technical issues, I find that they are more motivated to conquer the technical problems.

It is helpful not to start at the beginning of a piece every time. This heightens concentration and suggests the importance of being extra careful here. Simply starting at the beginning of every piece has a different effect on rehearsals. There has to be a plan. By always focusing on the micro-aspects, conductors strip the ensemble of all responsibility for the music. With less difficult music, conductors can rehearse the broader musical issues in a work. By teaching students how to listen using this approach to rehearsals, conductors will find many technical elements improve as responsibility shifts to the musicians. I do not stop every time something sounds out of kilter. Students quickly realize that they have to listen more and take greater responsibility for the rehearsal process. One of the best rehearsal techniques is not to conduct. Every time I analyze what was different when I didn’t conduct, the answer inevitably is that students listened more.

Score Study

By Gary Green

January 1998

Gary D. Green is Emeritus Professor of Music and Director of Bands at the Frost School of Music at the University of Miami.

In a score with any number of parts playing actively at the same time, I study each part and sing every single line in the score. To imagine exactly what a flute and oboe will sound like together is very difficult, but it is important to know how a combination of instruments will sound. You have to enter every rehearsal with a precise image of sound for the players, and it’s hard work to do that. If a score is extremely complex, I will ask a graduate student to sing along with me so I can hear how the parts fit together. I work with a metronome all the time in score study to acquire a good feel for the tempo and the rhythms.

Musical phrases are not necessarily musical sentences. They can also be questions, comments, or exclamations. Compositions can be viewed as musical conversations. The woodwind section may make a statement, the brass may interject something else, and so on. Each section takes part in the conversation. At a party, if everyone talks at the same time, the sound is overwhelming, and the ideas become nonsense. If everyone in the room focuses on a single thought, each comment is distinct and makes sense. I see music the same way. Each voice within the composition has to fit in with a preceding part and perhaps with another that occurs five minutes later. There should be a design, a reason behind the style in which each musical phrase is played. This is why I sing each phrase while learning the score. Balance stems from how each line is sung and how it fits in with the others.

Rehearsals

By Michael Burch-Pesses

February 1999

The career of Michael Burch-Pesses includes long tenures as a bandmaster in the United States Navy and as Director of Bands at Pacific University.

Use humor to cut tension.

Students do not have much fun when struggling with a difficult passage, but a humorous comment may ease the stress of a tense moment. Some conductors believe that humor has no place in a rehearsal. A certain degree of intensity is essential, but there is no need to be grim about. Anyone who doubts the effectiveness of humor in rehearsal should attend a clinic by W. Francis McBeth. His humor always relates to the music and often illustrates a musical point without ridicule or sarcasm. During one clinic a chord was out of balance. He said, “I hate that sound, and I wrote it!” The audience and the band laughed, and the clinic continued in a more light-hearted manner.

All too frequently conductors barrage the ensemble with insults throughout the rehearsal. I once heard a conductor say, “That note just sits there like a dead fish. Put some energy into it.” For many students, sarcasm and fear will impede their progress. Most students respond better to encouragement and respect than to intimidation. Humor can sometimes create the right atmosphere.

End upbeat.

Never end a rehearsal with difficult material but with a piece the group knows and can play well. Review material that reflects the progress the ensemble has made. This ends the session with the rewards of intense rehearsing instead of with frustration.

Good directors teach students how to work hard and become disciplined, but they also celebrate and enjoy the achievements of the ensemble. The process of creating music should be a joyful experience for everyone.